Contrasting Child Poverty in Finland and England in 2024

On 21 March 2024 the latest official poverty statistics for the UK were released. They mostly reflect the situation in England. These numbers are released at this time every year, but this time was shocking. The headline in the Financial Times that day was ‘Fastest rise in UK child poverty for 30 years’. As comparable statistics only began to be recorded thirty years ago, the rise may have been the fastest ever rise in child poverty in one year in UK economic and social history.

Amy Borret in the Financial Times reported the words of Alison Garnham, chief executive of the Child Poverty Action Group, who said the data was “shocking” and ‘that anything short of scrapping the two-child limit and increasing child benefits would be “a betrayal of Britain’s children”.’ Amy continued: ‘Campaigners and economists have been calling for the ruling Conservative government to scrap its two-child limit policy, which means that families who claim universal credit or child tax credit cannot do so for a third or subsequent child. The data also showed that income fell last year for all but the top 20 per cent of earners, with the largest reductions in the poorest households.’

Looking inside the new UK statistics reveals a portrait of Britain that is pitiful, especially for the 14.5 million children alive in 2022-23. One in eight children were by then growing up in homes where no adult had any work (two thirds with only a lone parent). One in three children were in homes with two or more siblings, so were hit by the two-child limit on child benefit that even the Labour party in England now supported in 2024 – note the Labour parties in Scotland and Wales have different views. In Scotland this cruelty to children in larger families is not permitted, and there is also an extra Scottish child payment set at a level to ensure that no child goes cold or hungry in Scotland.

Not so in the rest of the UK.

Across the UK as a whole, 5.4 million children by 2022-23 were living in a household where someone had a disability, but only 1.4 million of them lived in a family receiving any disability benefits. Some 3.2 million UK children have to live in the private rented sector and so could be evicted with two months’ notice, this equates to almost one in four of all children (and that proportion has been rising).

Children in the UK (other than in Scotland) are increasingly living parallel lives. Some 8.3 million UK children live in households with no savings or less than £1,500 saved for a rainy day. On the other side of the tracks 3.1 million UK children live in households with £10,000 or more saved away. Together, these are 78% of all children, only 22% of all UK children are not in the two extremes of wealth-poor, or wealth-rich, British households.

The latest UK government report revealed that 28% of all UK children lived in the poorest fifth of households. That is two in every seven children. By 2022-23, of these poorest of all, of the 2 in 7, the proportion that lived in the hardest hit families of all were:

- 23% that could no longer afford to keep their home warm.

- 32% did not have enough bedrooms for every child aged 10 years or over and of a different gender not to have to sleep in a bedroom with an adult or with a child of the opposite sex – they are thus suffering severe housing deprivation and may be at risk.

- 34% of these 2 out of 7 children live in homes that their parents can no longer afford to decorate at all, but where their parents wish they could decorate – they can no longer afford even the most meagre of decoration.

- 36% of their parents would like to be able to replace broken electrical goods like a kettle or a phone, but can no longer afford to do so anymore.

- 39% of their parents can no longer afford home contents insurance, so if there is a fire or flood or a theft – they will become destitute (if not already so).

- 46% cannot replace worn out furniture, a further 16% say that they don’t think about doing this anymore. So material standards of living fall all the time.

- 52% of these 2 in 7 children would like to have, but cannot afford anymore to have, at least one week’s holiday away from home with family in any year.

- A slightly different 52% live in families where the parents would like to be able to save £10 a month, but cannot. A much greater number have to choose between saving £10 a month, and home insurance, or a holiday, or fresh food, or heating, or numerous other very basic provisions.

The next 2 in 7 children were doing almost as badly. By most well-off folk’s reckoning, a majority of children in the UK are now poor in terms of how their lives are being lived (4 out of every 7 children in the UK).

These are the worst modern child poverty statistics I have ever seen and I only have space here to cover child poverty in Britain, and just to merely scratch the surface of the data that was released in March 2024 in the UK. Only the Financial Times and the Guardian reported the story in any detail and neither paper had space to include the above statistics or similar ones. The Guardian suggested that ‘Labour called the figures “horrifying” and promised to tackle the problem if it won power at the next election.’ However, Patrick Butler writing in that newspaper pointed out that the Labour Party had no plans to actually do so.

The UK has seen the greatest rise in child poverty reported anywhere in Europe. The rise has been lowest in Scotland although the BBC ran a disingenuous story on this under the headline ‘Child poverty in Scotland shows little change’. The BBC does not report how well Scotland does in comparison to England nowadays.

The situation in England is terrible. We already know that our children are increasingly stunted in height and that death rates for them are rising. What we may not realise is that even the best-off children are not doing well in the UK anymore. In contrast to our European neighbours they cannot expect to be as well educated, to have as good health, or to be housed as well.

Compare what is occurring now in most of the UK, where the situation continues to deteriorate as prices continue to rise faster than income and as inequality is not decreased, with other parts of Europe and Scotland. Everywhere reports the news as bad news. But in comparison to most of the UK and all of England, it often is not at all as bad.

In Finland, for example, a right wing government is now in control. But the contrast with England could not be more stark. However, if you read the reports on Finland the two countries can initially appear similar in terms of proposed economic and social policy. That new right wing Finnish government plans to make:

‘it easier to dismiss employees, relaxing regulations on fixed-term contracts, making the first sick day a day without pay, reducing unemployment benefits, restricting political strikes, capping wage increases based on export sector wages and easing local bargaining. The unprecedented scale of change is reminiscent of the reforms pursued by Margaret Thatcher in the UK or by Portugal under pressure from the Troika in 2011. However, unlike those situations, Finland’s economic situation doesn’t necessitate such reforms.’

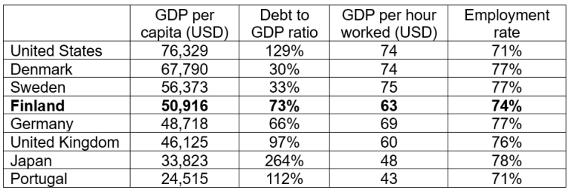

The report the quote above came from included a table of data showing that the economic situation in Finland was not that bad, as compared to the UK. Finns are not just much more equal than people in the UK, their overall GDP per capita is now much higher, they have less national debt, are more productive and have a similar proportion of people in work.

Table: Key indicators for the Finnish economy compared to selected OECD countries

Source: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2024/03/25/finlands-proposed-labour-reforms-risk-doing-more-harm-than-good/

Despite the Economic Situation in Finland being much better than in the UK, headlines in Finnish newspapers have still been disturbing in recent months. On 6 December 2023 one such headline read ‘Orpo’s government will increase child poverty, says a Finnish Unicef expert’ That report continued: ‘Finland has not succeeded in reducing poverty in families with children. This is what Unicef says, which compared the fight against child poverty in 39 countries between 2012 and 2021. Finland only ranked 14th. In previous years, Finland was in the top five.’

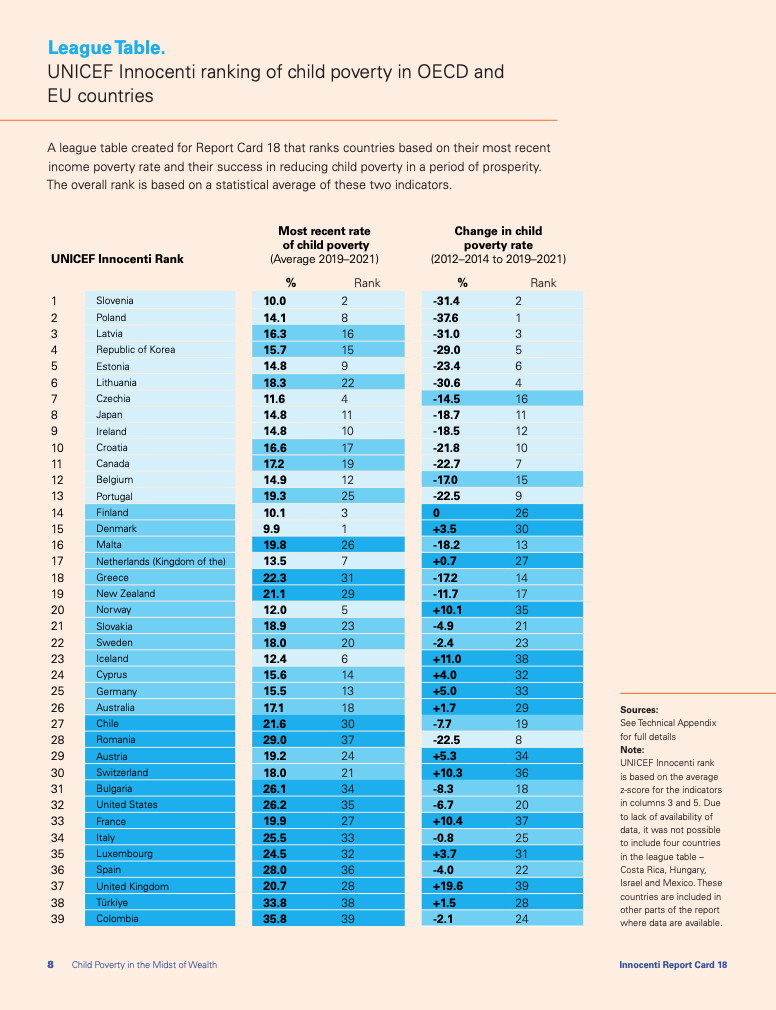

So Finland’s position has worsened, but this is not because child poverty there has risen. It is because other countries have improved faster. In fact, Finland only ranked 14th by change. Finland is still the country with the third lowest child poverty rate (10.1%). That is the third lowest of the 39 that UNICEF compare in detail (see detailed table below). Some thirteen countries saw faster improvements than Finland in recent years, but only one of those has a lower child poverty rate than in Finland. And the second best placed country of the 39, Denmark, did slightly worse than Finland in terms of change between 2012-14 and 2019-21.

Source: https://www.unicef.org/innocenti/media/3296/file/UNICEF-Innocenti-Report-Card-18-Child-Poverty-Amidst-Wealth-2023.pdf

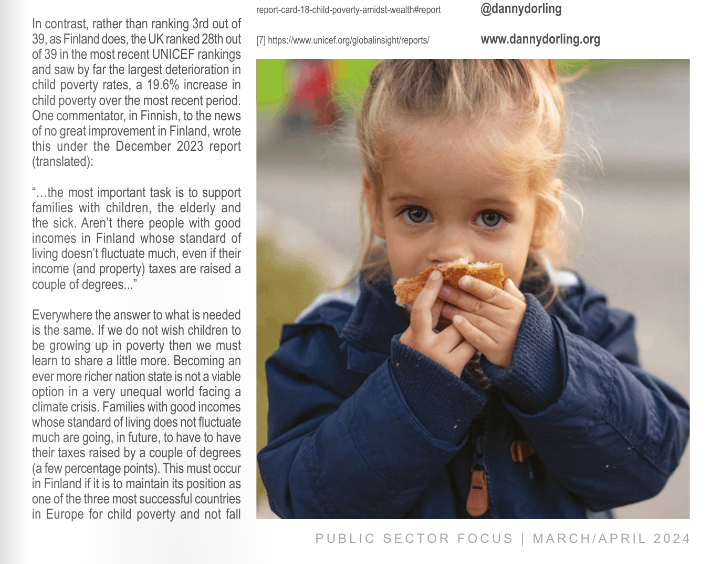

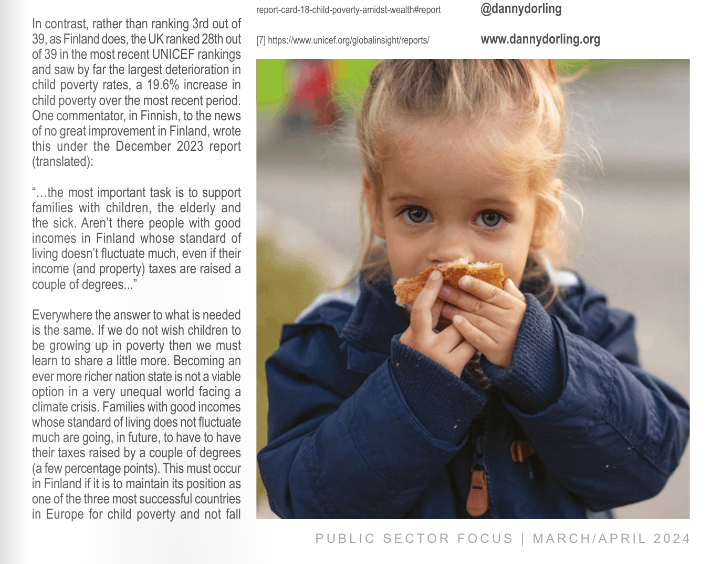

In contrast, rather than ranking 3rd out of 39, as Finland does, the UK ranked 28th out of 39 in the most recent UNICEF rankings and saw by far the largest deterioration in child poverty rates, a 19.6% increase in child poverty over the most recent period. One commentor, in Finnish, to the news of no great improvement in Finland ,wrote this under the December 2023 report (translated):

“…the most important task is to support families with children, the elderly and the sick. Aren’t there people with good incomes in Finland whose standard of living doesn’t fluctuate much, even if their income (and property) taxes are raised a couple of degrees…”

Everywhere the answer to what is needed is the same. If we do not wish children to be growing up in poverty then we must learn to share a little more. Becoming an ever more richer nation states is not a viable option in a very unequal world facing a climate crisis. Families with good incomes whose standard of living does not fluctuate much are going, in future, to have to have their taxes raised by a couple of degrees (a few percentage points). This must occur in Finland if it is to maintain its position as one of the three most successful countries in Europe for child poverty and not fall down the ranks. And it is desperately needed in England – where the change that is required is far greater and so much more urgent.

Danny Dorling – written for Public Sector Focus, 27 March 2024.

For a PDF of this article and a link to where it was first published click here.

Contrasting Child Poverty