The crises combine: austerity, cost-of-living, public sector jobs and pay

The UK government may be taxing people more (other than the very well off) than it has done in many decades, but that does not mean it is spending more on public services in real terms, or even living up to what it has previously promised to spend.

In April 2023 it was quietly announced that the Sunak government had halved the funding it had promised to help support the social care workforce. In December 2021, when Sunak had been Chancellor for almost two years, a promise had been made to invest ‘at least £500m over the next three years’ into social care. This was part of the White Paper on adult social care reform. Fifteen months later, in April 2023, that promise was halved to £250 million.

The learning disability charity Mencap reacted angrily, labelling the U-turn as an ‘insult’ and explaining that ‘the plan had now been diluted beyond recognition.’ [1]. There are currently 165,000 too few care workers in place and now there is little hope this will be remedied. One consequence of the previous cuts to social care spending had been rising mortality in Britain since 2012 among many at risk groups, especially the most frail and elderly. When the promise was broken, the charity Age UK explained that funding was no longer even ‘remotely enough’. The King’s Fund health think-tank was also damming in its assessment. The Trades Union Congress labeled the U-turn: ‘slashing’. The GMB union, which represents many care workers, called the decision, ‘disgraceful’.

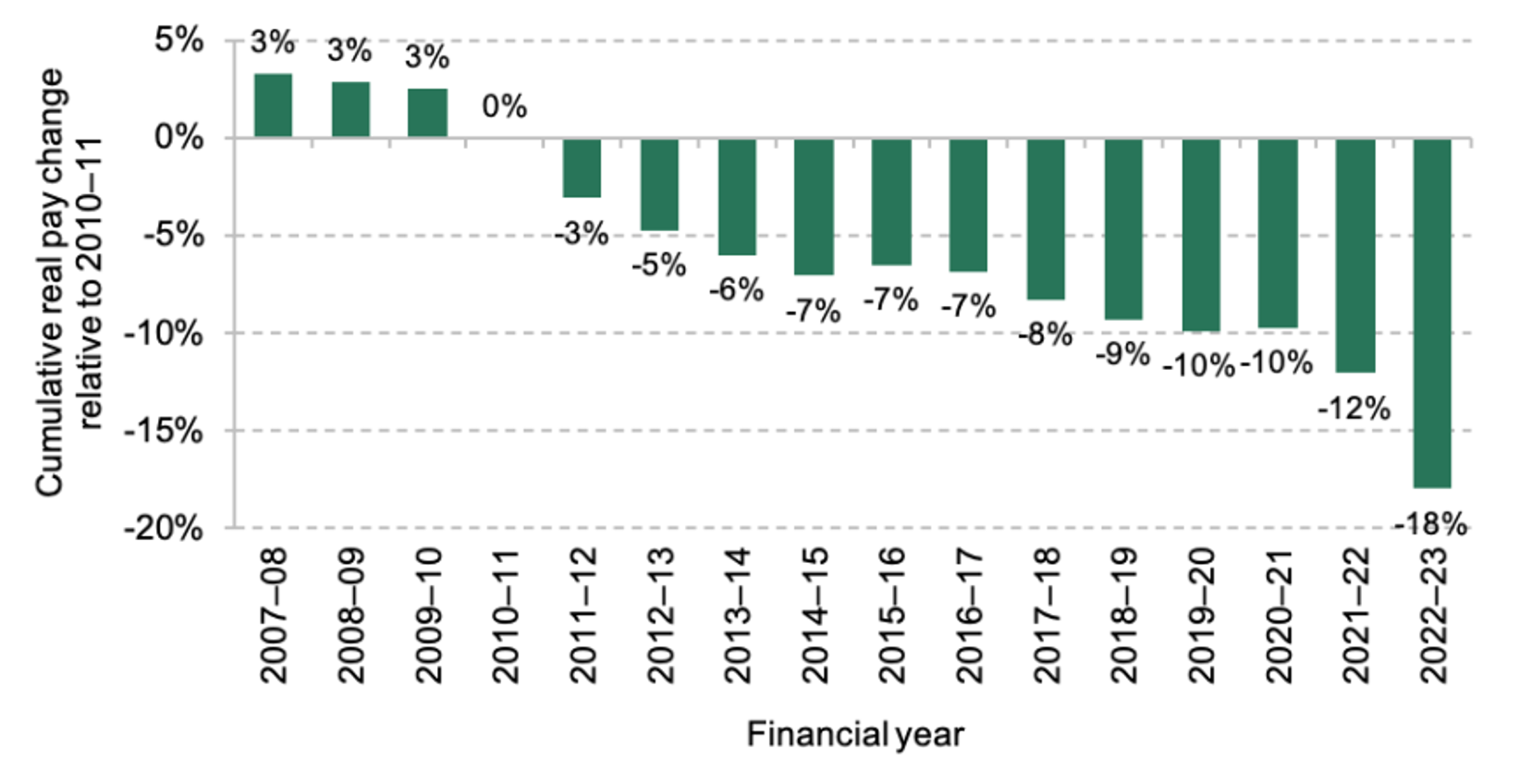

Cumulative real-terms pay changes for FE staff relative to 2010–11, 2007-2023 (source IFS)

Earlier in the spring of 2023 the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) had noted a dire situation in another state sector: Further Education, one which employs 50,000 teachers. The IFS noted that by 2023, in today’s money, the median pay for a school teacher had fallen to £41,500 a year, but for a Further Education college teacher is was now only £34,500. In real terms, between 2010–11 and 2022–23, the median salary for a school teacher had been reduced by 14%, but the median salary for a college teacher had been slashed by 19%.

As a result of worsening conditions and declining pay , some 16% of all Further Education college teachers leave the profession each year. This compares ‘with 10% of school teachers, 10–11% across most NHS occupations and 7–8% in the civil service.’ [2] The cut in real terms pay was far worse in the most recent year (2023) as compared to any other year, possibly any year since Further Education began. In the 1970s pay tended to increase above inflation. How had we got into this state and what is to be done?

On 29th November 2022 the Office for National Statistics, in effect, nationalized the Further Education college sector by reclassifying it in the public accounts. Further Education colleges were made public bodies overnight, not private anymore. Suddenly those who run them can no longer be paid more than £150,000 a year unless they seek the special permission of government each and every time they try to do this. [3] The government immediately declared that ‘Following the reclassification, colleges and their subsidiaries are now part of central government.’ One implication was that no one in the sector could be paid more than the Prime Minster. Those Further Education bosses who had been setting the salaries of college teachers so low now had to look at their own pay. [4] This is a start, but there is so far to go.

These are just two parts of a British public sector that have, as a whole, now been decimated many times over, but all this is part of a much longer process. It began in the 1970s when the fight to protect jobs and the public sector more widely was lost. The public sector and decent progressive taxation had been won in the 1920s and 1930s through a huge amount of collective action, not least by people striking for their rights.

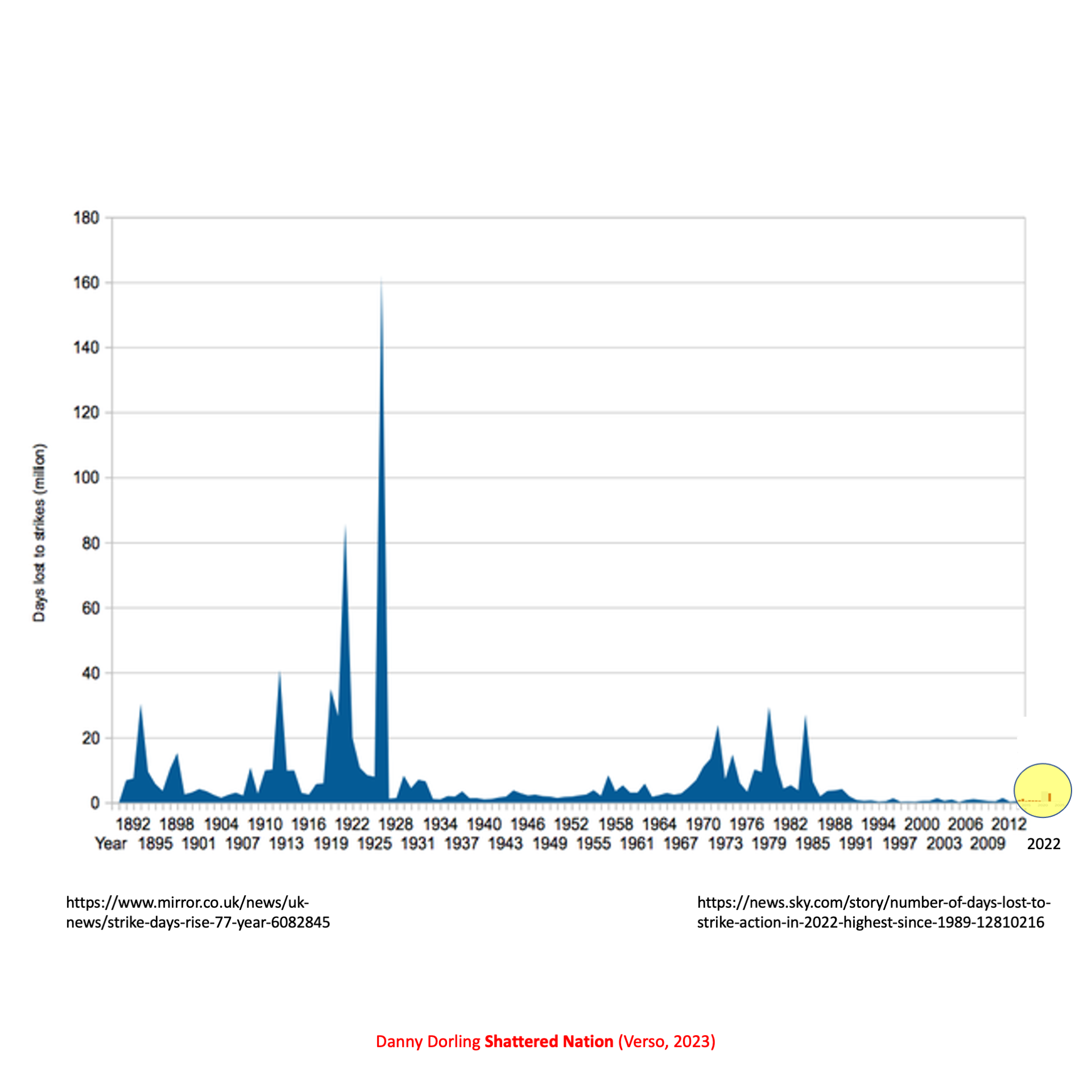

The strikes of the 1920s were successful in contributing to rising equality, both at the time and especially afterwards. The wave of strikes that began in the 1970s dwindled after the defeat of the miners in 1984/85. The wave that began in 2022 is still extremely small, and has to be highlighted to be visible in this historical series. This is despite the workforce being far larger today and the graph not being corrected for that population growth.

We are still living in a land that was poisoned by Thatcherism. We were brought low by a doctrine of ‘me-first’ selfishness that continues to hobble really effective action. We were torn apart in the 1980s as inequality soared back up to levels not seen since the 1920s. We have not recovered any ground at all. Inequality is now embedded at a very high level.

Socially, the UK is more starkly divided than any other state in Europe. We have a multi-tier education system, a two tier-health system (private and state), and a chasm between those who rent or own their home. And strikes are on the increase again, but as yet are not that widespread. Living standards will continue to fall even as the rate of inflation falls, because prices will still be rising faster than prices for some time to come.

Numbers of days lost per year due to strikes in Britain, 1892-2022 (source ONS)

Politically, the UK is riven with divisions that reflect our underlying economic and social severing. The resentment is rising, and many attempts are being made to stop it becoming more focused. Brexit and the culture wars are still being exploited by charlatans. They have fertile ground to till as social division results in short fuses and little patience and tolerance. We desperately need a more cohesive society with a much higher degree of trust between people and – eventually – a renewed sense of common purpose. The UK is such a long way from this.

Not everything can blamed on Thatcherism. Labour and the Liberals must take part of the blame. Especially in England where there has been such an enormous failure to think differently. New Labour offered a methadone alternative to the Tories’ heroin. It alleviated a few of the symptoms, but we are back and hooked on the true opiates again now. You cannot kick the habit by just watering down the product.

The Corbyn project was viewed by many as an impossibility. However, all it really offered was a bit more tax and spend. This is how salted the earth has become. Even modest proposals have been ruled out of bounds; but today nationalization of Further Education and much else, from Railways to Housing Associations, becomes forced on us or at the very least a topic for consideration, as the privatization experiment of 1980-2020 crashes and burns.

Policy solutions abound – green deals, wealth taxes, common ownership of utilities and public services, a growing co-operative and employee-owned business sector, but they are hard to introduce and sustain while our politics remains poisonous.

As Daniel Chandler recently explained in his book “Free and Equal” (endorsed by Vince Cable Angus Deaton, Stephen Fry, Andy Haldane, David Miliband, Jesse Norman, Amartya Sen, Minouche Shafik, Thomas Piketty, Rowan Williams and Linda Yueh) that we need an entire over-haul of our electoral system, proportional representation, strict controls on any individual person funding political parties more than any another, and very high levels of progressive taxation. I am not sure all those who endorsed the book read to the end and saw the conclusions being made before they wrote their words of praise; but maybe they did.

Proportional representation and a constitutional overhaul are the building blocks required. They seem beyond reach at the moment, but to construct anything you first have to visualize and articulate it, so let’s at least do that with energy and hope. The alternative is no care in our old age, no teachers for our children at college, and little decency left in public life.

As the crises combine and continued austerity mixes with a cost-of-living nightmare, as public sector jobs are being lost and pay in real terms is cut, There are some real signs of hope: nationalization returning and progressive pay deals becoming the norm. [5] However, the sun-lit uplands now appear to be so far away that is easy to give up hope. Perhaps this is what it will take for change to come? The bad times still have to run their course for it to be clear just how wrong the ideas that got us here were.

References

[1] Adam Forrest (2023) Tory ministers accused of ‘insult’ to social care as workforce reform funding halved, The Independent, April 4th, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/social-care-funding-tories-sunak-b2313677.html

[2] Luke Sibieta and Imran Tahir (2023) What has happened to college teacher pay in England?, Institute for Fiscal Studies, March 30th, https://ifs.org.uk/publications/what-has-happened-college-teacher-pay-england

[3] Julian Gravatt (2023) Are universities really at risk of ending up in the public sector?, Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI), 21 March, https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2023/03/21/are-universities-really-at-risk-of-ending-up-in-the-public-sector/

[4] Department for Education (2023) Further education reclassification: government response, Policy Paper, November 29th, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/further-education-reclassification/further-education-reclassification-government-response

[5] Dorling. D. (2023) Are things about to get better? Prospect Magazine, April 5th, May issue, pp.38-41, https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/essays/have-we-reached-peak-inequality and at https://www.dannydorling.org/?page_id=9653

For a PDF of the original article and a link to where this was first published, click here.