Most people in the UK now share Robert Owen’s views

From 1798 to 1822 Britain suffered it longest ever fall in wages and a huge drop in living conditions due to prolonged wars in Europe alongside the early effects of new technology and industrialization. This was a 24 year record which will only be broken if real wages do not recover to the levels the reached in 2008 until after 2032. That is possible very possible – but it can be averted.

Prolonged cost-of-living crises, coupled with high inequality, have often brought about profound change. In 1817, after almost two decades of this national suffering, the Welsh business man, Robert Owen, turned to what was then called socialism. On March 12th he wrote to the chair of the House of Commons committee discussing the Poor Laws. Owen outlined a ‘New View of Society’ to the committee.

Owen appealed to the self-interests of the new capitalists. He proposed that in future life in Britain would better be organised along communal lines, with communities the size of the model village of New Lanark in Scotland. Robert Owen had become the manager of the cotton mill in that village in 1800. He had slowly come to understand that if things carried on as they were, this would end in disaster. Life expectancy fell.

Slave picked and planted cotton had become more expensive to import into Britain after the American plantation owners won their independence. The British mill owners tried to minimise their potential loses by making their workers toil harder for less reward. The mill owners left labourers to fend for themselves and argued for small government and low taxes.

Robert Owen suggested that communities should be collectively organised; that education should be provide by the community, beginning with free child care for all from the age of three. These communities would work together, aided by government, to ensure that standards of living rose and that life could be enjoyed. Ideas like his spread, but it took time for them to be enacted. The Poor Law he so opposed was not abolished until 1948.

From 1921 to 1931 Britain suffered its next longest fall in wages. The Prince of Wales met hungry miners in 1929. There had been a general strike, then a banking crash and mass unemployment. Inequality was again at an all time high. Most of the rest of the colonies were followed the United States and fought for independence. Ireland split off. Britain was becoming poorer again. Inequality in the UK began to fall. The rich were being taxed more than they ever had been before. Greater changes then came in the 1940s and 1960s in a form that Robert Owen might well have recognised as mirroring many of his ideas (including establishing playgroups).

From 2008 onwards, Britain suffered its next longest fall in wages. Scotland introduced new Child Payments and in November 2022 increased them to £25 per child per week aged 16 below, for all children living in families in receipt of Universal Credit or other state benefits (what could be thought of as yet another new Poor Law). Although the Scottish Child Payments were entirely affordable, Scotlands’ other ambitions to be a better country with free university education, a high quality health service, and good housing for all, were not achievable given the funding existing arrangements with Westminster. By 2020 it became obvious it would soon become untenable for Scotland to remain in the Union.

But what of Robert Owen’s dream of quality childcare and pre-school education? In 2023 it was revealed that the average hourly pay for people looking after children in our nurseries is now only £7.42. That is much lower than the minimum wage because of sexism. Almost all early years workers are women. Many are classed as apprentices and so can be paid lower than the national minimum wage.

In April 2023 the minimum wage was £10.42. It was only £10.18 for 21-22 year olds; £7.49 for 18-20 year olds; and just £5.28 for 16-17 year olds. The national minimum wage for apprentices is even less: £4.81 per hour. Should you wish to compare this to what you were paid when you were young, that wage is the equivalent of receiving the following hourly pay in the past:

2010: £3.40

2000: £2.76

1990: £2.12

1980: £1.22

1970: 38p

1960: 26p

1950: 18p

1940: 11p

1930: 9p

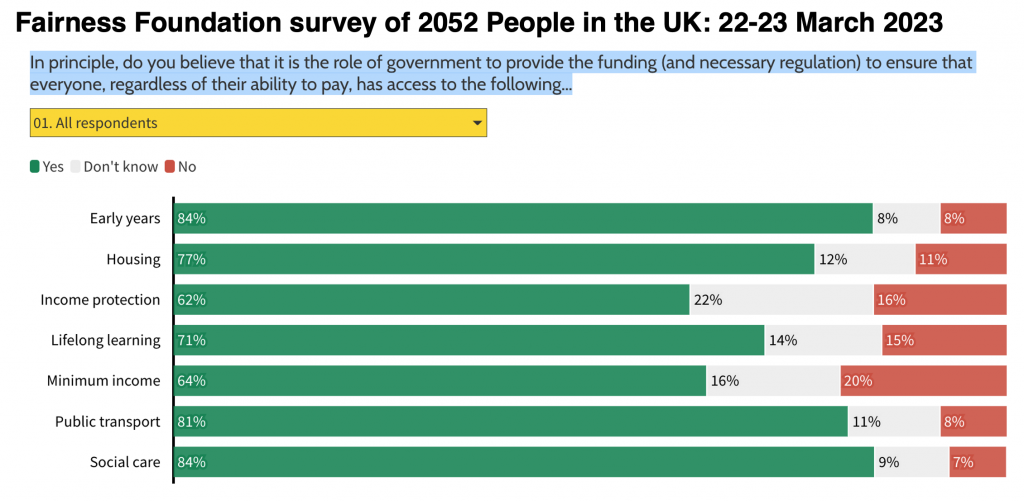

A few weeks later, the Fairness Foundation reported that when polled, more than four in five people in Britain agreed that the government should fund minimum levels of provision for social care (84%); for good quality childcare and pre-school education (84%); and ensure cheap public transport (81%). More than seven in ten agreed that government should provide the funding to ensure basic decent provisions in relation to social or rented housing (77%); and lifelong learning (71%); and more than three in five agreed that the government should provide a to minimum income (64%); and also that people who lose their job should be paid a percentage of their income by government to help them get back to work (62%).

Fairness Foundation Survey: https://fairnessfoundation.com/role-of-gov

In their press release, the Fairness Foundation explained that a shift towards huge popularity for these stances began long before 2023. That shift was now imbued in many of those who were doing well of themselves too. The economist, Minouche Shafik, then Director of the London School of Economics (LSE), a Board Member of Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and a former the Deputy Governor of the Bank of England, had written a book: ‘What We Owe Each Other: A New Social Contract’, back in 2021, and the Foundation cited that as an example of how these beliefs were becoming much more widespread.

This trend is accelerating, in 2023 Daniel Chandler, an economist and philosopher based at LSE, published a book titled ‘Free and Equal: What would a fair society look like? The former chief economist of the Bank of England, Andy Haldane greeted its publication as ‘energising and timely’. David Miliband, who had once been Britain’s Foreign Secretary, claimed it was: ‘clear, brave and compelling’. Rowan Williams, a past Archbishop of Canterbury, described it as: ‘exceptional’. The national treasure, Stephen Fry, summarised Free and Equal as: ‘…timely, wise, authoritative and clear’. Minouche Shafik urged people to: ‘Read Free and Equal and feel hopeful about the future.’

So what was in the book that had so excited these luminaries? It is possible that some of them did not read through to the latter pages, but maybe most of them had? The second half of his book is better than the first. In it Daniel Chandler writes approvingly of how Belgium limits the amount any individual can donate to a political party to €500 per year. He suggests that it should be a little less than that, with the state matching personal donations or even exceeding them.

Chandler writes in supportive terms about the introduction of a Universal Basic Income. He suggests that there is no evidence of any economic detriment from very high taxes, although he is unsure of whether tax rates of over 75 per cent on incomes of over $500,000 a year might encourage tax avoidance. He describes inheritance taxes for billionaires of 80 to 90 per cent that should be a first priority and shows that – combined with decent income taxes on capital – ‘a seemingly low annual wealth tax of 1-2 per cent could see some people paying most if not all of their capital income on taxes’ (page 238).

Why were so many of the British great and good drawn to these suggestions, people who had not advocated such policies so vocally before 2023? The answer might be that they were simply now fitting in better with the common attitudes of the rest of society. Our times are changing rapidly. Chandler suggests that his ideas are not socialist. But socialism has many meanings. At its heart it means to be social. Robert Owen, on his death bed in1858, claimed: ‘My life was not useless; I gave important truths to the world, and it was only for want of understanding that they were disregarded. I have been ahead of my time.’

For a PDF of this article and where it was originally published click here