What would it take to persuade Rishi Sunak to join the Patriotic Millionaires?

I suspect they would agree to him joining, were he to ask. He is, after all, both patriotic and a multi-millionaire. I believe that he could understand their arguments, should he wish to. However, he would have to discard some of the beliefs he has picked up over the years, possibly from as early as his school days. That is difficult for anyone to do. Sunak has written three publications that help explain where he is coming from: A Portrait of Modern Britain (2014), A New Era for Retail Bonds (2017) and The Free Ports Opportunity: How Brexit Could Boost Trade, Manufacturing and the North (2018). He would have to rethink a lot of what he wrote and believed then to be persuaded.

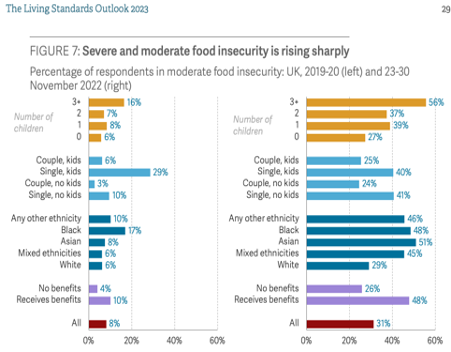

However, the countries of the UK have changed greatly since he wrote those tomes. In 2023, a majority of children in larger families in Britain were going hungry ever month. Sunak may begin to realise that something has gone badly wrong, and that the promises that we would one day reach the sunlit uplands – the promises that his party have given every year from 2010 onwards – were false promises. He may be persuaded by the evidence and do the maths.

Ultimately, it is down to his aspiration. Does he aspire to be to be the kind of Conservative Prime Minister who is remembered, such as Disraeli or Macmillan, for moving towards a one-nation conservatism, in outcome and not just in rhetoric? Or would he be satisfied with being a footnote? Most past Conservative Prime Ministers are no longer remembered. Most are merely footnotes.

Sunak’s one great skill, where through real work experience he is far more qualified than any previous Prime Minister has ever been, is that he understands what would be required to tax the wealth and income of the rich properly and prevent them using loopholes to evade such action. Why waste such a talent?

What role do you think land value taxation could play in helping to resolve the housing crisis, especially the problem of ever-increasing house prices?

Even in a society without land taxes, house prices are never ever-increasing. The best long term data series that demonstrates this is from the Netherlands.

The longest house price series in the world (this graphic is from the book ‘Slowdown‘).

However, without land taxation (and other forms of wealth regulation), a society is doomed to keep repeating the spiralling booms and crashes of the past. The Dutch in previous centuries have demonstrated to us what a free market achieves and how inefficient such a market is where housing is concerned. Countries such as Austria that better regulate their housing have better housed populations. The USA has some of the worst housing outcomes in the rich world. Seventy years ago the UK was the envy of the world in terms of its housing policies because of what those policies were achieving.

Land taxation can be a part of that solution. One great advantage of land is that you cannot hide it. Again, Mr Sunak’s super power, his special skills, could be harnessed to address this problem. He has greater experience than any other Member of Parliament concerning the ownership of multiple valuable homes and other assets, including owning a very large property in North Yorkshire.

It may sound ridiculous to suggest that he might apply his skills in this area; but perhaps one reason why Conservative party members did not vote for him to be their leader was that some of them realised that he knows, should it be required, how what may have to be done can be done. He may not like the idea, but people can learn and begin to question their instincts. It was mostly Conservative Prime Minsters that were in power for the period from 1920 to 1970 when Britain last became so very much more equal. They may not have liked it, but in various ways they aided it, because there was no other acceptable option.

Would a land value tax not lead to increased food prices if most farmers own their land? Or should it only apply to residential land?

A land value tax should apply to all land. Once you begin to introduce loopholes, people will start to claim that the gardens of their Mayfair mansions are farms. The value of agricultural land without development permission tends to be very low in comparison to other land, so the tax would be very low too. The price of our food has little to do with British farmers. It did not rise by a fifth in the last twelve months because we had bad harvests in Britain. Other countries in Europe successfully control the food prices people have to pay. The Greeks even do this on food sold on their beaches and in other public places. If people ever tell you that something is not possible, first look to see what is happening elsewhere in Europe and then ask: “if it is possible there, why is it not possible here”?

How can the law be changed so that the wealthy are subject to it in exactly the same way as people with less wealth?

That would best be done if someone who knew the wealthy well was involved in drafting the law. Similar things have been achieved in many impressive ways in the past. For instance, when the National Health Service was created doctors were, at first, offered the salaries that they had been reporting to the tax authorities. When they complained that they could not live on such little money, they were offered a bit more. However, the minister, Bevan, did not publicly shame them, instead he said that he had “stuffed their mouths with gold”, which may have made them feel more respected.

Wealth taxes can be enforced simply by changing the law to state that you do not own an item, land or shares, that you do not pay the proper tax on. People are very keen to pay stamp duty on houses because otherwise they do not own their home. One of the most effective ways of changing the law so that the wealthy pay their taxes is to do what is done in some Nordic countries where the tax that everyone pays is published annually and anyone may view it. You can easily discover if your neighbour with three very large cars outside their property is declaring very little income. Others will be nosey but they may choose to say nothing. However, wealth tax dodgers do tend to make annoying neighbours; and even the thought of possibly being investigated tends to encourage the wealthy to be cleaner.

Imagine that any of your friends, neighbours, work colleagues, ex-partners, annoyed siblings, or other rivals might be tempted to point out to the authorities that you appear to be stealing from the people (evading tax). Such openness may be impossible to imagine ever coming to Britain; but have you ever stopped to wonder what the sunlit uplands actually are? Sunlight is the best disinfectant; ultimately, it is transparency that eventually ensures that the wealthy are subject to laws, such as on taxation, as much as the rest of us.

There are many other ways in which the wealthy can abuse the law: malicious prosecutions for libel and slander are two examples. In the end, the wealthy are treated much more like other people when they are less wealthy. In Britain they became dramatically less wealthy one hundred years ago. In the decades that followed most could soon no longer afford servants. Hardly anyone ever complained that they, or their children, could not be servants.

Would you ban private schools to achieve social justice?

No, because it is not necessary. Finland, one of the countries with the best state education systems in the world, still has a few private schools. It does not have many such schools, because it makes very little sense for a parent to send their child to one. But it is a useful check on the state system to allow private schools to continue so that you can monitor the numbers going, and then know if you might have a problem in the state sector if that number rises.

There are some private schools in Britain that occupy geographical positions in cities which do prevent a good network of state schools being established because, in the very middle of all the state secondary schools, there is a private school that would be an ideal hub state school. Often that private school was established as a public school, supposedly for the poor. So only in those circumstances of geographical necessity, which are very rare, would I suggest nationalisation.

The Borough of Kensington and Chelsea may be the most affected, where a majority of children attend private schools, which makes establishing a well-connected geographical network of state schools in that borough difficult – schools between which teachers and pupils might travel to teach subjects that not enough pupils in any one school study, for example.

Tax breaks and other concessions from private schools should be removed. They cannot be thought of as charities if the word charity is to mean anything in future.

Furthermore, I would worry about boarding schools. When I was young I was told about the problems in boarding schools. Now I am old, I am still told very similar stories today. However, parents are increasingly choosing not to send their children to such schools. This is an issue of social justice even if it is about justice for the children of the extremely wealthy. If you are interested in fairness you cannot just be concerned with the poor. The children of the very rich can suffer too, sometimes in ways that are less likely to happen to poorer children.

Is it fair for society to allow people to live in poverty? If not, should everyone be forced to work to the extent that they are able to?

No, it is neither fair, or necessary, and certainly not inevitable to allow people to live in poverty. Work is not the route out of poverty. Britain has far more people in work than almost any other nation in Europe as a proportion of its adult and child population. Britain also now has some of the worst levels of poverty in Europe. It was revealed in 2022 that the poorest fifth of families in Britain were poorer than that same group in some Eastern European countries.

In early 2023, the head of economics at Bloomberg suggested that this might well have increased to being poorer than the poorest in a majority of Eastern European countries. In no other Western European country are so many people now so very poor and in no other do people work so hard, for such long hours at work, and for so many years of their lives, for such low pay, retiring so late in life (and dying so early).

Work does not set you free; but it can be rewarding if you have freedom at work and freedom to choose to work – or not to work. In the future, we will need far more people than now not to be in paid work. This is the future that John Maynard Keynes talked about in 1930 when discussing the economic possibilities of our grandchildren. The opposite to what Keynes imagined occurred, but the result of working harder was not riches. In future if we are to consume and produce less, we need fewer people trying to get us to consume and produce more.

The city I live in, Oxford, produces more cars than it has ever done, but with fewer people that have worked in its car factories since shortly after they were established. Today, one electric Mini a minute roles off the production line, made largely by robots.

In some ways Keynes’s future is here, but what he did not predict was that it would take us more than three generations to learn how to embrace it. We have to give people the option to be lazy, not just the idle rich. Given that option, studies have found that most people actually make far better use of their time then they would if forced to work. No employer who cannot attract people to work for them should be in operation.

What role is there for economic, social, and cultural rights in the fight for social justice?

Economic, social, and cultural rights are best won in societies that are more equal by income. The economic right to live in a comfortable home without damp is best achieved where peoples’ incomes are more equal and landlords have less power. The social right to partake in the norms of society, to be able to have a holiday away from home (and not just staying with family or friends) is almost universally achievable in such societies – and was in Britain in the past. The cultural right to dress as you wish to dress and be who you want to be is more easily attainable where groups are not viewed with suspicion because of the fear that income inequality feeds.

For example, nowhere in the rest of Europe, except for the former British colonies of Ireland and Malta, retains or enforces school uniforms for children. In Britain we just think this is normal, but what of the cultural rights of children to dress how they wish?

Securing greater income inequality is the trump card. It is even more effective than securing greater equality in wealth. Where income inequality is high, racism tends to fester and grow. Where and when it is high, more people are seen as undeserving and we become used to seeing others sleeping rough on the streets; we begin not see them as people. Where income inequality is high, we are more likely to become obsessive about the life choices of others and not live and let live. Where income inequality is high, we are less free to be who we want to be, and with who we want to be with.

There’s been a lot of talk recently about a new ‘woke elite’ who don’t represent the views of ‘ordinary people’. What’s your take on this argument?

I think it is helpful that it has been raised because it begs the question: ‘what would a society in which the woke were the elite look like’? Woke means awake. It means those who understand. The word comes from America, from the descendants of slaves. Today it describes being alert to racial prejudice and discrimination.

We are currently governed by people who say that Britain, and the past actions of its agents, can never be painted as the villainous. A villain, in the past spelt ‘villein’, was a feudal tenant entirely subject to the whims of the lord or manor to whom dues were paid and services rendered in return for being allowed to work the land. The word villain today implies lower class scoundrel. In August 2022, Rishi Sunak proposed that people who suggest that any of British history might ‘vilify the UK’ should be referred to the ‘Prevent’ counter-terrorism scheme for re-education. We are not living under a woke elite – quite the opposite.

In November 2022, Jeremy Hunt, speaking as Sunak’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, stated, without equivocation, that ‘the United Kingdom is and has always been a force for good in the world’. When Boris Johnson resigned as leader of the Tory party on 7 July 2022, in his resignation speech he repeated George Osborne’s 2015 promise that if only we keep on doing what he wanted us to do, then soon ‘we will be the most prosperous in Europe’. Osborne’s had said ‘in the world’. Their horizons were narrowing. Both Osborne and Johnson implied that such a move would return Britain to its rightful place.

Imagine in a fairer future a different group governing us. A group with a better grasp of history, who know what so many people in the rest of the world now understand about Britain and the role the British played where they live. That group would include a wide variety of views from a much wider variety of backgrounds than our current elite. Some of the them might believe in ‘no gods, no masters, no heroes, and no vanguards’. Others would have very different views. However, it is unlikely that any of them would worship the god of mammon (money), and they would not view themselves as elite, special or different. In these imagined sunlit uplands, the phrase ‘ordinary people’ would be remembered as something that the old elite used to say, because they thought of so many other people as beneath them – as ordinary.

Danny’s opinions are his alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Fairness Foundation.

for a PDF of this article and its original place of publication click here