A Letter from Helsinki

I arrived in Helsinki in early summer 2022 to attend Europe’s largest conference on social housing. At the airport I overheard American tourists complaining that so many shops were shut. It was a Sunday evening. The tourists didn’t understand that Finland has the best work-life balance in Europe. I wondered why people who have just embarked from a plane want to immediately go shopping. Perhaps it was just what they had become used to?

I listened to hundreds of social housing planners, architects and housing managers, people from all around the continent of Europe, talking to each other in a language most of them rarely use on a daily basis – English. There were only a few people from the UK there, and I kept quiet on all the tours I attended. I was trying to avoid being asked about what was happening back at home by curious mainlanders.

Providing housing of high quality, at affordable rents, is a distant memory in the UK. Just before I travelled to Finland the British government had announced that it intended to introduce the right-to-buy for housing association tenants. It wasn’t that I was ashamed of being British. I was just tried of trying to explain what was happening to the place I called home.

I attend field-trips, one to see the new residential district built on a former industrial harbour very near Helsinki city centre where tens of thousands of people now live in mixed developments under a plethora of schemes including a social housing block planned for retired rock musicians, complete with sound proofed music rooms! A passing tenant whispered to me that it is not quite the Utopia my hosts were describing – a place where everyone gets on with everyone else. I nodded, I knew it is not Utopia, but I wondered if he knew what the conditions for him would be if he lived in the United States, or the UK?

All is not perfect in Finland. The queues to access the best social housing are many thousands of people long. However, almost no one sleeps on the streets, even in the twenty plus degree heat of a Helsinki summer. In the evenings I tried to spot people who are street homeless – and I failed.

A heat wave was building up strength further south. I counted myself lucky not to be sweltering in that while I traipsed around newly built block after block of carefully designed dwellings. An architect talked of how many of her colleagues competed to design one particular block. University students show me their state-built and state-managed studio flats, each complete with kitchen for one. Hardly any students rent in the private sector. In Finland almost three out of every five university students have their own public-sector provided apartment and choose not to share.

I learn that in Norway new housing for students is based on a dozen or even more having rooms in a large shared house or apartment with a big communal kitchen – to reduce loneliness. Young Finns appear to place a greater value on having their own space. Perhaps to shelter a little from some of the conformity? But will other Finns at some point begin to resent the mostly middle-class university students having such homes? Students coming from over-seas are allocated this housing first, as they are seen as being at most need. Can you imagine any of this in Britain? Extremely quality housing provided and managed well on the basis of need with foreigners at the front of some queues?

Back home, in England, another of the Prime Minister’s many ethics advisors had just resigned. I asked if any Finnish government minister had transgressed a single regulation during the pandemic. My hosts scratch their heads, debated among themselves and finally replied ‘no’. I asked them why it took them so long to agree and they say they were also debating whether ministers did things they were allowed to do, but should not have done, so as to set a better example. I laugh. I tell them about the government-chartered plane that had recently been prevented from leaving Britain to fly refugees in harnesses to Rwanda. They did not know about it. Why should they? Britain is an ever more alien place to them, a land of atrocities now so frequently committed that most are no longer news on the European mainland.

Attending more talks, I heard details of the huge differences across Europe in terms of what is currently possible when it comes to housing people adequately. One common theme was that the costs of construction materials has risen so high and so quickly that almost everywhere new social housing building is currently being placed on hold. Only the most affluent more egalitarian countries might secure the dwindling supply of girders, wiring and piping this year. The Norwegian government is now looking into spending far more than it usually does to ensure that building public housing there continues with little interruption.

I only spoke at the very end of the conference. I tried to be tactful, after all who I am – given where I come from – to offer useful insights? I told my audience of my country which, by the time I was born, had managed to house a narrow majority of its young adults during their childhood in social housing of ever-growing quality – a higher proportion than in Finland today. It was a country with lower wealth and income gaps than those seen in Finland today. This was a country then leading the world in increasing the social mix of children in its schools. It was a country whose health service ranked above all others. That Britain is just a distant memory now.

I asked what will happen if the cost of building construction continues to be so very high in Europe due to the aftermath of the pandemic and the new war in Europe? When they can no longer so readily build and provide for their poorest, will the most affluence and equitable countries in Europe learn to share what they already have more? Or will they say that everyone has to tighten their belts equally in straighten times, effecting those with least the most, and see justified resentment grow?

Less than fifty years ago planners, architects, educational researchers, and ministers of health from across Europe came to the UK to see how social housing, schooling and hospitals could be best provided. We in Britain had a social contract that appeared strong, but when the prices of construction material and oil rose with inflation in the 1970s. The contract then began to be broken, it started in the mid 1970s – and never ended.

I show my audience graphs of how the number of children growing up with a private landlord sky-rocked not in the 1980s, but in the 2000s. I say, it is not so much the conservative you have to fear – you understand them. It is when your own side becomes complacent and corrupted that you are in most trouble. Beware when social democrats believe they have achieved so much and done so well, that asking for even greater equality (of ‘outcome’) would be asking for ‘too much’.

I tell my audience that the most common way people die under age 65 in my home city of Oxford is to die homeless, and that it has been this way for over two decades now. I congratulate the delegates because children born in almost all their countries now have lower infant mortality than in the UK, and the Finns recently achieved the lowest rate ever recorded in history, which of course has as much to do with their housing, social and education policies as with their health care. I thanked my hosts for having invited me. And ended by telling them that at least they have the example of the UK to warn them of what happens when you stop caring enough; we didn’t have such a useful example in the 1970s. We didn’t know how bad it could become and how so much could be lost.

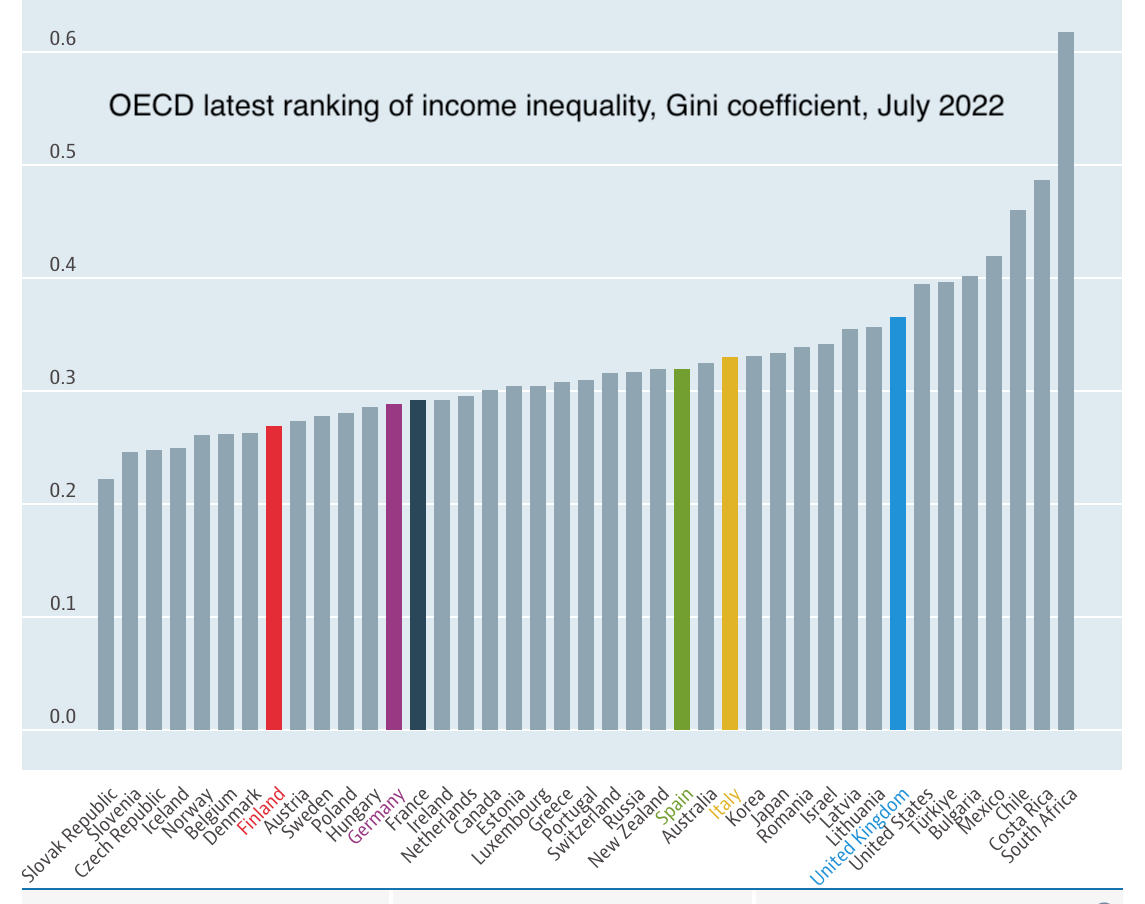

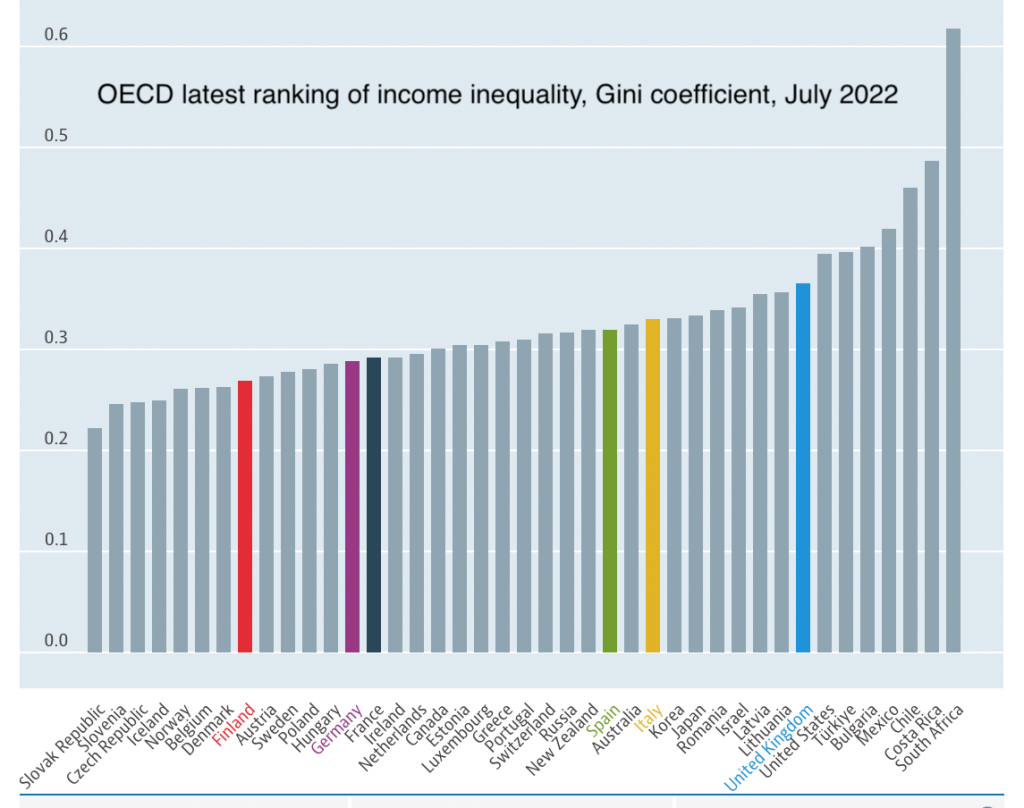

Source of data: https://data.oecd.org/inequality/income-inequality.htm

Shown here is one graph that sums up where we are. It is the basic graph of income inequality that compares all OECD countries. The graph reveals that Finland is exceptional, but no longer unusual. Shaded in red it is now not quite as equitable as Denmark, Belgium, or Norway; and only a fraction more equal than Austria, Sweden and Poland. Increasingly, more and more of Europe is becoming like Finland. Germany and France are not far behind – shaded purple and black on the graph. Spain, and Italy, shaded Green and Yellow, are on the slightly less egalitarian side of the centre of the distribution. The UK is on the edge. In all of Europe only Bulgaria is more unequal. The UK has much more in common now with the USA, and is far less similar to most of its own continent when it comes to inequality. We have to look to the USA, or perhaps more plausibly to nearby Turkey, or at the very extreme towards South Africa, to see in which direction we are heading.

You might think that it would be impossible for our inequalities to grow higher,. But we broke away from what is normal and possible when we broke out of the EU. We are now even more economically unequal than Israel. We are now firmly in the group of OECD countries where populations live parallel lives and politicians talk freely and without much criticism about the poor needing to take ever more personal responsibility. Politicians in these most unequal of countries enact laws in the name of freedom to make it easier for a few to exploit others. We have become the place on our continent to travel to, if you want to see what a broken society looks like.

I try to imagine what Europe’s largest conference on social housing would look like if it were ever held in the UK. Where would the fieldtrips be to? Would university students happily stand at the doors of their incredibly expensive privately provided accommodation and say how lucky they were to be living there and getting into so much debt? Would some of the incredibly well paid chief executives of housing associations try to suggest what a brilliant model the UK had with so much housing being charitable? Would representatives of our huge plethora of homelessness charities stand up and extol the virtues of there being so much opportunity to work in the homelessness sector as homelessness here was so high? Would the delegates from the mainland walk out of the conference? Or would they quietly take note of what happens when the public sector is so shrunk and so deformed. Not just in housing, but in education, health and care too.

I’m glad I saw Helsinki again. In the past it was an unusual beacon of hope. Today what happens there is increasingly the norm elsewhere in Europe. The Nordic model is slowly becoming the normal model.

Source of data: https://data.oecd.org/inequality/income-inequality.htm

For the original place of publication and a PDF of this article click here.