The end of great expectations?

The pandemic inquiry must account for stalling life expectancy before the pandemic, Editorial, British Medical Journal

Life expectancy at birth is a key summary measure of the health of any given population. Ideally, it should increase steadily over time in the absence of data artefact, mass migration in or out, or a large scale event such as war or natural disaster, disease outbreak, or societal collapse. Any break in the trend beyond isolated annual fluctuations should raise the alarm among health workers, policy makers, and the public.

The covid-19 pandemic has caused life expectancy to fall below predicted levels worldwide, including in the UK.1 Part of this may have been inevitable given what we now know about this new coronavirus, but part could have been avoided. The inquiry into the UK government’s handling of the pandemic is essential,2 not least to provide answers to the tens of thousands of bereaved families who are rightly asking whether more could have been done to save their loved ones.

When the UK inquiry takes place—public hearings are likely to begin in 2023 (the Scottish government’s inquiry may start in 2022)3—it must also consider what was happening in the UK before the pandemic began. This is essential to ensure that the population harms caused by covid-19 are measured accurately, taking full account of prevailing trends before the pandemic. By March 2020, decades of progress in improving life expectancy had already stalled, and for some groups, reversed. Women over 65 years old were the first to experience falls in their life expectancy.4 In 2018, the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) reported a fall from 82.72 to 82.67 years for women of all ages between 2011 and 2012.5 Subsequently, more groups and communities have experienced widening inequalities and declines in life expectancy,6 including women at and below the second most deprived decile in the Index of Multiple Deprivation.7 Most recently, life expectancy declined for people at and below the fourth most deprived decile between 2015-17 and 2018-20.8

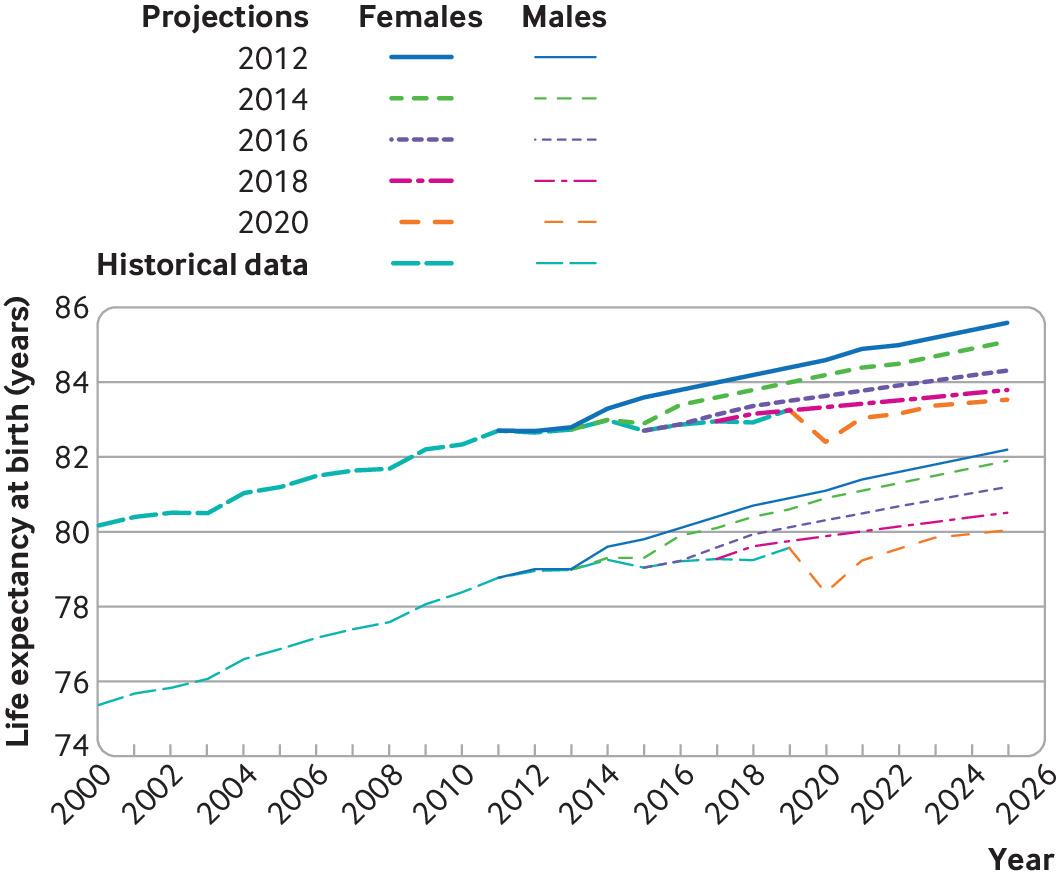

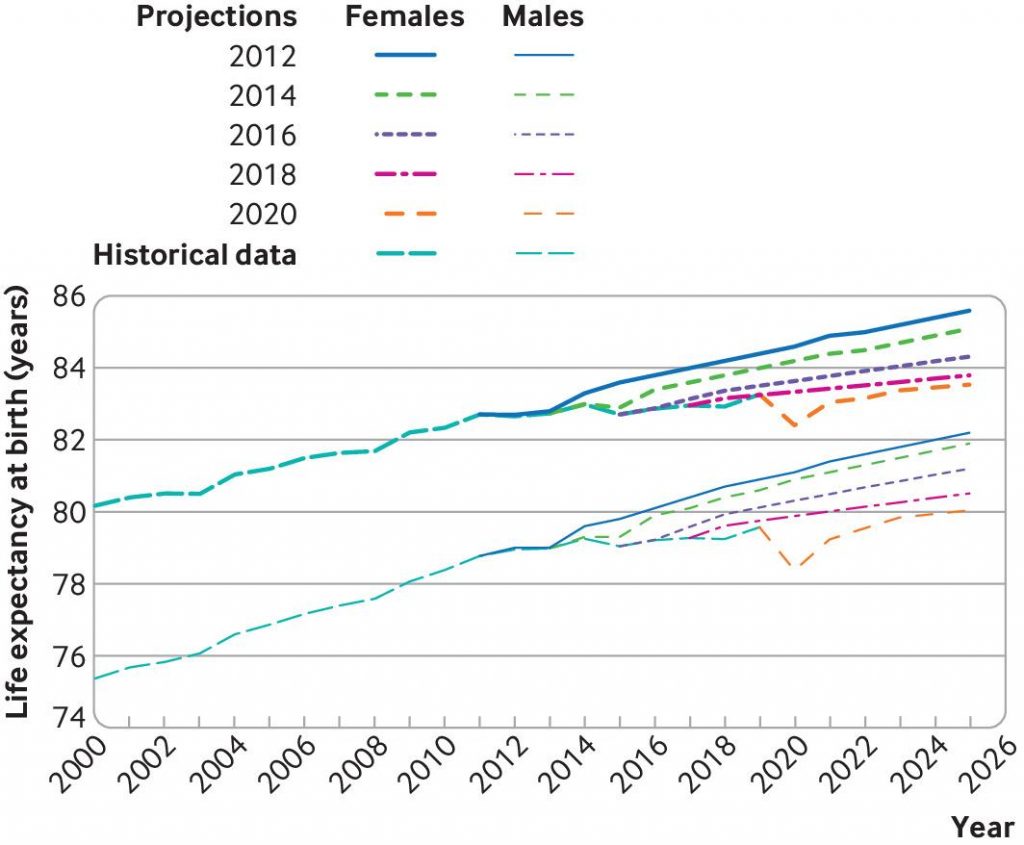

In January this year, the ONS published an update of its regular life expectancy projections using the latest population estimates and data on life expectancy, up to and including 2020.9 Figure 1 shows these and previous projections for both males and females in the UK.

Fig 1

Projections of life expectancy at birth for males and females in the UK, 2012 onwards. The dotted lines show the actual recorded historical data from 2000 to 2019, and the solid lines show ONS projections made every year from 2011 to 2025

The recorded historical data, represented by the dotted lines, show that life expectancy fell for women briefly after 2011 and for both men and women more substantially after 2014, before rising above the 2014 levels in the year before the pandemic. Between 2012 and 2014, projected life expectancy for people in 2025 fell by 0.5 years for women and 0.3 years for men. Between 2018 and 2020 the same projections fell by 0.3 years for women and 0.5 years for men. In other words, the fall in projected life expectancy caused by the first year of the pandemic was comparable with a similar fall in the early 2010s.

Importantly, estimates of excess mortality linked to the pandemic compare mortality in 2020 and 2021 with a five year average—including the period between 2015 and 2019 when life expectancy was stalling. This distorted baseline (with higher mortality than might be expected historically) may lead to underestimation of the true excess mortality caused by covid-19. We should aspire to a higher level of population health than we had in 2015-19. Notably, the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries covid-19 action taskforce used 2019 alone as its baseline,10 but even that number is lower than all of the four most recent previous ONS projections made for 2019.

Other high income countries also experienced falls or stalls in life expectancy between 2014 and 2015.511 However, when trends for 18 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development countries were examined, researchers found that all countries except the US and UK recovered with “robust gains” in 2015-16.11 The US is poor company to be in with regard to population health: life expectancy at birth there has declined annually since 2015, except for a small increase in 2019, with increasing inequalities in age at death.12 13

These latest ONS data suggest the UK was an outlier among comparable countries, with worsening population health in some years before covid-19.5 ONS projections of life expectancy are likely to be revised down further when the 2022 based projections are published next year or in early 2024, as these will include far more complete data on covid-19 deaths in 2021 and 2022.

To be fully comprehensive, any inquiry into pandemic deaths must also investigate the underlying causes of the concerning trends in life expectancy over the decade before the pandemic began. Those same causes, which are presumably ongoing, probably exacerbated harms done by the pandemic and may continue to cause serious harm if they are not acknowledged and urgently tackled.

Footnotes

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare that we have no competing interests.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

For a PDF of this article and link to original source click here.