This is what peak inequality looks like

We can find it hard to believe that an era has come to an end, that a peak has been passed. But when, finally, such a change happens the memories of commentators change with it. They will say that they believed the change to be desirable all along, that they somehow saw it coming and so, too, were on the side of history. Then we can all forget that just a few years previously they had so vehemently opposed change, had justified the status quo, were so scornful of those who suggested change was possible and ultimately were so wrong.

[This is an edited extract from the book Peak Inequality which will be debated at 7pm on Wednesday July 11th 2018 at the London Review of Books bookshop, tickets here]

Britain has been governed by an unusually shambolic administration in recent years. Some thought of it as venal—motivated by “big money.” Others saw the Conservative administration as being self-interested, and uninterested in the plight of the majority of people, but interestingly even these politicians have recently had to move towards the left. Little of this was recognised early on by the news media, which initially proceeded in its usual deferential manner. However, the actions of the 2015 government also led to radical politics rising up again within the Labour movement. The democratic socialist Left within the Labour Party’s burgeoning membership won two leadership contests, then cut a Tory majority down to a minority government, and now that Labour Party looks set to have a good chance of winning power, possibly in coalition with the SNP. We are living in strange times; times which might well in future be understood and reinterpreted in the context of what becomes possible when a state approaches peak economic inequality.

In comparison with the recent past, the chance of Labour winning power is now so high that by January 2018 the Financial Times was advising its more affluent readers to think of unwinding all their secretive family trusts and other financial “structures”—the ones that they may have put in place to avoid paying taxes—before any new general election as “Labour has said it wants to see the public disclosure of trusts, which it describes as a key vehicle for tax avoidance and illicit financial flows.” That advice only makes sense if the Financial Times saw a Labour victory as plausible, and likely to be followed by very quick action by Labour politicians to identify tax avoidance.

It is far from fanciful to suggest that what brought all these events to such a crescendo was incredibly high and still rising income inequality. When income inequality is high, the richest try harder than ever to avoid paying taxes as they amass so much wealth that could be taxed. The repercussions of living with high inequality, the highest in Europe, are like living with a ticking time-bomb. When economic inequality is very high, so much then goes awry in education, housing, health and welfare, due to the efforts of those who think they benefit from such inequalities trying so hard to maintain them.

Extreme inequality is maintained by misleading the public. Initially voters were told that it was the fault of the 2005 Labour government, rather than the bankers, that there had to be cuts. Then benefit scroungers were blamed, then immigrants, then EU regulations holding back global free-trade and undermining the mystical power of sovereignty. These were lies that would fuel the Brexit vote. But still the inequality time-bomb is ticking. Brexit is partly an attempt by the very rich to keep the tax haven status of London and overseas territories unaffected by EU regulation.

If you want to know who is pulling the strings you follow the money. That money was used to feed the fear that globalisation was impoverishing people in the UK. That money was spent by the owners of tabloids telling readers that all would be well when the border was secured against immigrants. Simultaneously the rich would be free to squirrel their money away over that border with no future EU oversight.

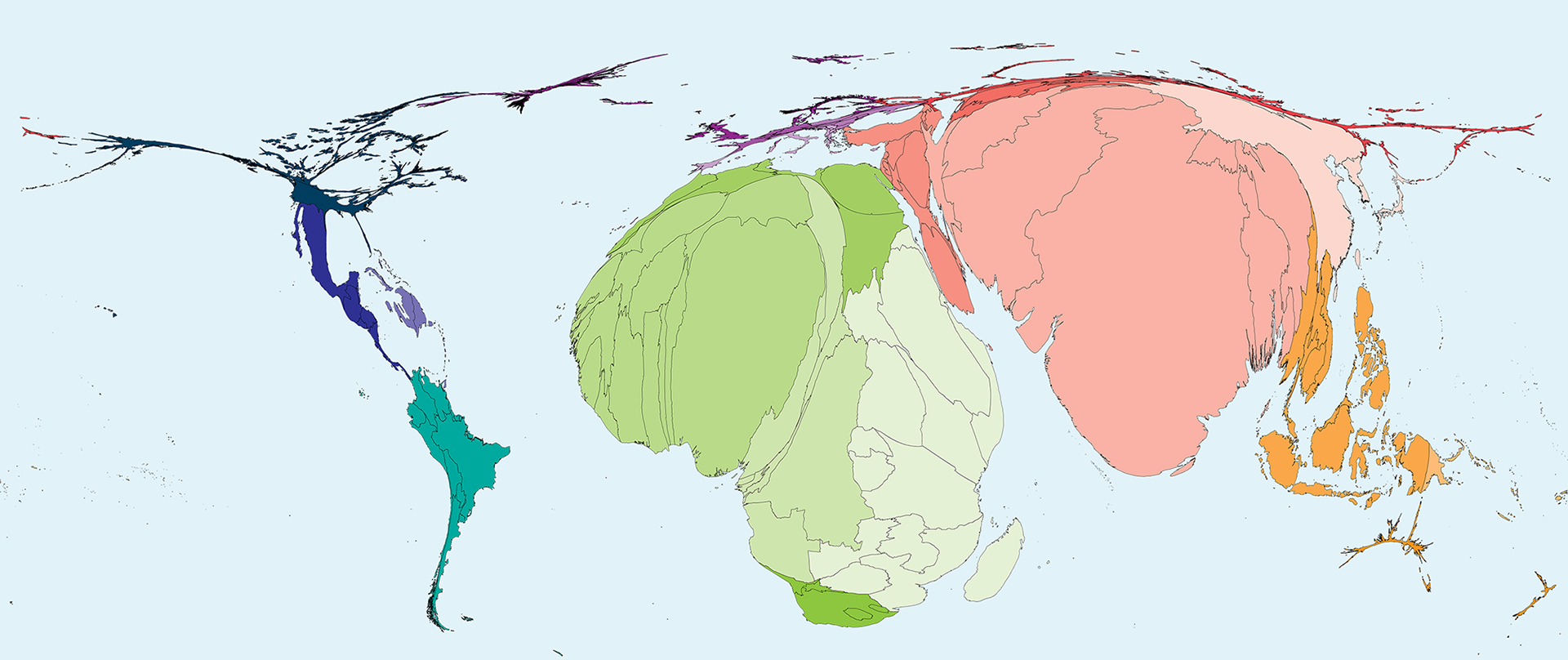

It is geography that best reveals the effects of economic inequality. Geographical comparisons allow us to see how much better almost all the more equitable countries of Europe have been governed, with better outcomes. By contrast, in the United Kingdom and the United States, as inequality rises these societies begin to tear themselves apart. The rich spend more and more to try to live far away from the poor, while simultaneously making more and more people poorer. However, spreading poverty and precariousness wider also fuels the time-bomb.

I am often seen as an egalitarian, but I expose what I find because I am a geographer and see what geographical comparisons reveal. I know that people do not have equal ability. We all have very slightly different genetic make-ups. However, it has always been clear that there was no way that the bizarre geographical distributions which social cartography reveals to be so extreme within the UK could have anything to do with genetic differences.

I have met many people in high positions, particularly in academia and government. Hardly any warrant being labelled geniuses. All have had their own handicaps. The most impressive have tended to be humble, and quite rightly so. These are (or were) people seen to be at the top of their fields. However, they did not get there by some inbuilt super-potential, but because of opportunity, chance, hard work and their individual reactions to their own handicaps and life events.

There is not, and never was, any “natural” hierarchy of human beings. British geographers have more reason to know this than any other group of academics. The history of British geography is littered with colonial racists who achieved little of lasting worth, but who thought they were members of a superior race and wrote this into (now) old geography textbooks that, with embarrassment, we try today to ignore. What we need is to teach the errors in what they said, so that the next generation is better able to spot closet eugenicists and racists than we have been.

One indication that we have hit peak inequality is so much going so wrong at the same time, as it did in the years leading up to 1913, the time of the last peak. Extraordinarily in 2018 we have rapidly falling levels of home ownership, far fewer secure tenancies, rapidly rising and exorbitant uncontrolled private sector tenancy rents, and—most recently—the potential for a housing price crash. This has all contributed to unprecedented post-war wealth inequality. There is little that is fair about how we are now housed.

Between 2010 and 2016, homelessness rose, rents rose, personal debt rose, housing prices rose, and the unpopularity of those who caused all of this rose among a growing majority of the young. By August 2016 it became clear that house prices in London had begun to fall. The then very recently sacked George Osborne had tried hard to ensure that property prices would continue rising and, consequently, to ensure that largely home-owning Tory voters would feel wealthier. Schemes to help first-time buyers were poorly disguised manoeuvres to boost housing value for the already well-off. All this while Osborne had recently done everything he could to propel London towards his vision of what the most economically successful city in the world should look like.

For Osborne, a successful London would also be the most expensive large city in the world. A place where the rich would be served by an army of ever more “productive”—but always relatively poor—labourers. He failed because no matter how hard you try, you cannot keep increasing income and wealth inequalities indefinitely. Do that and you stoke up the ingredients for a great catastrophe in the very near future. Like an addict, Osborne had kept on trying to stimulate the housing market with yet another hit of money from his “Help to Buy” schemes, but he was already clearly failing long before he was forced out of office by the political gamble of the European Union referendum.

On being handed office with no contest and without having to outline any plan or aspiration beyond one very short speech given only very shortly before she became the only candidate for Prime Minister, Theresa May (and her new Chancellor Philip Hammond) had no new ideas on how to gradually deflate the housing bubble. In the face of clear trouble ahead and in an attempt to make her position more secure, she tried another political gamble, a general election, in which she lost the majority that had put her in power. The (net) swing to Labour in June 2017 was unprecedented. In size it was similar to the swing that brought Labour to power in 1945, but it occurred over the two years from 2015, not the ten from 1935. Corbyn is just another sign that times are a changing.

May has never won a majority in a general election or even a leadership contest in her own party. Without a clear reason she was awarded the ultra-safe seat of Maidenhead in 1997 when she was aged 40. By early 2018 a house no larger than a train carriage cost £300,000 in Wheatley, the previously very normal and affordable Oxfordshire village where May attended grammar school. House prices in 2018 across the home counties, along with so much else, appear to have a reached a peak in 2018.

But house prices should be the least of our worries. More than 103,000 children were homeless in the UK on Christmas day 2015, almost all of them in England. That figure rose to 124,000 in 2016. By Christmas 2017 the estimate was of approaching 130,000 children waking up in temporary B&B accommodation on Christmas day. Then fire broke out in Grenfell tower and the country woke up to the housing catastrophe. It is one of a series of simultaneous catastrophes that are not uncommon in countries which become so extremely inequitable at the peaks, when things fall apart.

We are already seven years into a health disaster, while almost all of the rest of the world is making progress the UK no longer is. Outside of the UK (and the US) life expectancy was continuing to rise in almost all other rich countries as well as in almost all poor countries. The future population of the planet will now be both a little smaller and a little older than had been thought likely in 2010. There is a good news story out there, just not here. By 2018 it became even clearer that humanity was settling towards a new demographic worldwide equilibrium. We had passed the global peak in births in 1990 and the peak of that generation’s own children much more recently. Infant mortality is plummeting worldwide, and in every country in Europe; apart from the UK.

In March 2018 it was reported that UK infant mortality had risen significantly for two years in a row. This had followed severe austerity and real-terms spending cuts. In June 2018 the Office for National Statistics reported that: “The age-standardised mortality rate for deaths registered in Quarter 1 2018 was 1,187 deaths per 100,000 population—a statistically significant increase of 5 per cent from Quarter 1 2017 and the highest rate since 2009.” We know the health crisis is at a peak as 5 per cent rises in mortality cannot carry on for very long at all. Not outside of wartime. Not without a remarkably callous government.

Education has seen similarly calamitous trends as in housing and health. The introduction of the highest student fees in the world for the vast majority of English students during 2012 has led to a new generation beginning to realise that they have been very badly short-changed. There is not space here to talk about what has happened to schools across England and the terrible waste of money that has accompanied academisation, followed by real terms spending cuts in budgets that were supposed to be ring fenced.

Nor is there space to write about the crisis in mental health, in prisons, in social services, the spread of precarious low paid employment and the fear of many of now having to work with no retirement in future. But there is also an opening up of hope out of this inequality disaster. Top incomes have stopped rising. The take-home share of the 1 per cent has fallen in the last three or four years. The reported average remuneration of the highest paid UK CEOs of the largest companies fell last year. And while we may suspect that they have found another way to pay themselves, such reported falls are the first in my lifetime (and I am not young).

The wealth of the richest is still rising, that is true. Wealth tends to lag income over time, but the wealth of the richest is far less when measured in dollars rather than pounds because the pound has fallen so rapidly in value as inequality has peaked. There are many silver-linings.

Peak inequality is no time of celebration. The way down from the peak of injustice and unfairness is often slow and meandering. Conservatives governments begin to increase taxes on private landlords, cap increases in student fees and promise real rises in public health spending, again to be paid for by increased taxation of the affluent—what had until recently been anathema to them. After over four decades of always shuffling to the right, the UK is just beginning to take its first tentative steps to the left again. Once you begin to step left it can take a long time to stop. Income inequalities fell all the way from 1913 to 1978; that period was the last time they began to fall like they have—only just—begun to fall now.

The most recent two Conservatives governments have not taken these steps to the left willingly. The tip-toeing only began with the 2015 administration and the shuffling has become more pronounced since June 2017. They are being dragged leftwards by an electorate unwilling to take any more extremism. And they are also being dragged to the left by the fear of the alternatives which are far more radical than any opposition party has presented for at least three decades. For instance, the SNP, which became the third largest party in UK politics in 2015, is politically normal by European standards but radical by British norms. And the Labour Party is currently slowly becoming again a typically European large social democratic left-wing mass membership party—not the place that it was until recently, a place where mild-mannered Tories could feel at home, if never much loved.

As we step over the peak of inequality we see a new landscape ahead of us. It is a landscape where, as we travel downhill, with every year that passes our political parties become more normal again. The political distance between each remains the same, but they all shuffle to the left as they step downhill.

As we come down from the peak we should expect our children to become less educationally segregated. They are currently the most segregated by school of any children in all of Europe. We should expect what were the lowest paid jobs to become both better respected and better paid. Simultaneously the most ludicrously over paid will see pay fall or at the very least eaten away by inflation and more progressive taxation. This hurts little as when all top pay falls, housing prices at the top also fall and they can all still afford the same home!

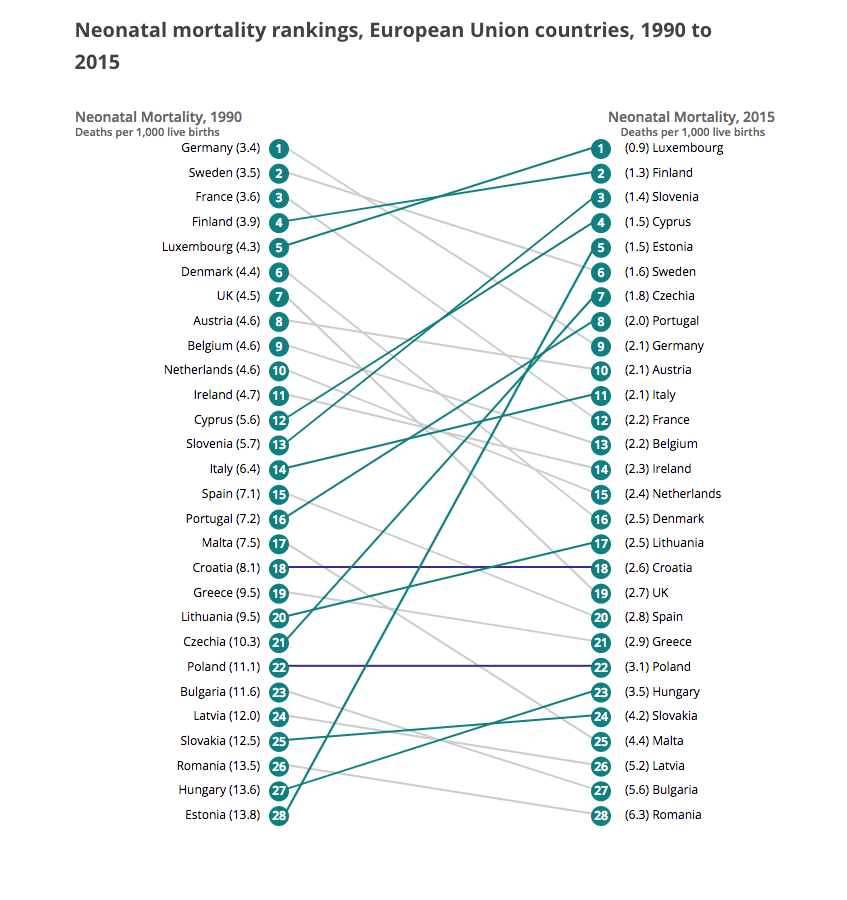

We should expect housing quality to rise while at the same time it is shared out better and better with each passing decade, as from 1921 to 1981. Much more importantly we should no longer see our ranking by neonatal mortality fall from 7th in Europe to 19thin the 25 years to 2015 (see chart below). And we should no longer be used to having the worst performance in adult life expectancy in all of Europe. We should have some decent time to spend with our grandchildren. It is not much to ask for.

Dorling, D. (2018) This is what peak inequality looks like, Prospect Magazine, June 28th PDF and on-line version Thsi is an edited extract from Peak Inequality.

Neonatal mortality rankings, European Union countries, 1990 to 2015