Playing chicken with voters

In September 2025, the British Election Study (BES) team released the latest results of a continuous survey of voters. What they were interested in was the decline in support for the Labour Party since the General Election of 2024. A year on from that election, support for the party of government had plummeted. The team summarized this thus: “Labour’s support has splintered into mostly indecision or left-liberal parties, but they’ve also lost their few right-wing voters.”1 For as long as it had been carrying out these post-election polls, a drop in support of such magnitude in such a short space of time had not been recorded previously. It is fair to say that the current volatility is unprecedented.

Half of those who had voted for Labour in the General Election of 2024 said that they would not have done so again if there had been an election in early summer 2025. The first figure here summarizes the changes and also helps to explain why political party strategists in Britain may be making certain assumptions that it could be dangerous to make. To understand that we have to look through the latest voting swings in some detail.

James David Griffiths, Ed Fieldhouse, Jane Green, and Stuart Perrett, ‘Looking for Labour’s lost voters’, The British Election Study, 3 September 2025

James David Griffiths, Ed Fieldhouse, Jane Green, and Stuart Perrett, ‘Looking for Labour’s lost voters’, The British Election Study, 3 September 2025.

First, look at how the 2024 Labour support has split and where so much of it has gone to. Losing the goodwill of half of your supporters is very hard to do in such a short time. One way of trying to understand why support fell away so fast is to consider the direction of where it went to. No other political party suddenly appeared to be a wonderful new home to head for. Most people who said they would no longer definitely vote for Labour ticked that they no longer knew how they would vote or had become undecided. However, despite the “Don’t Knows” receiving so many Labour votes, the size of that group did not grow overall. The next two largest groups headed to the Greens and the Liberals, but they were small groups of voters, just as small as was the group of Labour voters who said that they would now vote for Reform. The swings in votes thus displayed the effect of disillusionment, not a rush to one alternative.

Second, look at the Liberal Democrats. Their net support hardly changed at all over the course of this most recent year. That was despite that party also losing the loyalty of almost half the people who had voted for them in 2024! British voters are increasingly fickle; loyalties are easily switched, making predicting the future a much more dangerous game than it was in the past.

Third, look at all the minor parties: the SNP, Plaid, Greens and others; these are the next groups shown directly below the Liberals in the diagram. The nationalist voters were the only groups that tended to stay loyal. Nationalism, the hope for independence in Scotland and Wales, is a long game. The SNP had also done badly in 2024, so were holding on to their most loyal voters. In contrast, the Greens had done well but did not lose much support and grew in strength because of defections from Labour. In contrast again, the votes for other very minor parties splintered but the others picked up just as many from elsewhere and so remained tiny but persisting. All these polls were taken before a “left party” (that has yet to choose its actual name) was haphazardly formed in the autumn of 2025. The temptation to form a “left party” is more obvious when you consider just how volatile voters were becoming. It is easy to see why later national polls suggest that as many as one in five voters might at some points consider voting for such a party,2 and also why that proportion could crumble a few weeks later at the chaotic formation of that party. It might just as easily rise up again in future.

Fourth, please pay the most attention to the grey “Don’t Know” block. People do not like saying that they do not know, and so far fewer said they did not know than actually did not know or could not be bothered to vote in the 2024 general election. Because of this, when you look at the grey bars in the figure above, try to think of them as being representative of a far greater group of people than are implied by the figure. That group gained most from Labour and lost most to Reform. Voters almost never move from Labour directly to Reform.

Fifth: Reform – the light blue/cyan, chunk of voters that has doubled in size in such a short time. Reform did this firstly by losing hardly any of the supporters they had in 2024, secondly by picking up a large chunk of Conservative voters, and thirdly by taking a sizable number of Don’t Knows. I labour these facts as some strategists assume that because these silos are where the support has come from, most of the growing strength of Reform is limited, “capped” by the availability of people from these positions. That would be foolhardy to assume, not least because the “Don’t Know” pool remains just as large as it was before, and is in reality larger than surveys imply.

Sixth, and last, spare a thought for the Conservatives. Despite seeing their support fall to an unprecedented low in 2024, they managed to lose almost half of those supporters again in the space of around a year! Note also that although they lost the most to Reform, they also lost a sizable number to the now newly undecided. The Conservative Party is a very old party and remains the official opposition. Unlike Reform, it has a party structure, proper local branches, and a history. Nevertheless, it is in dire straits.

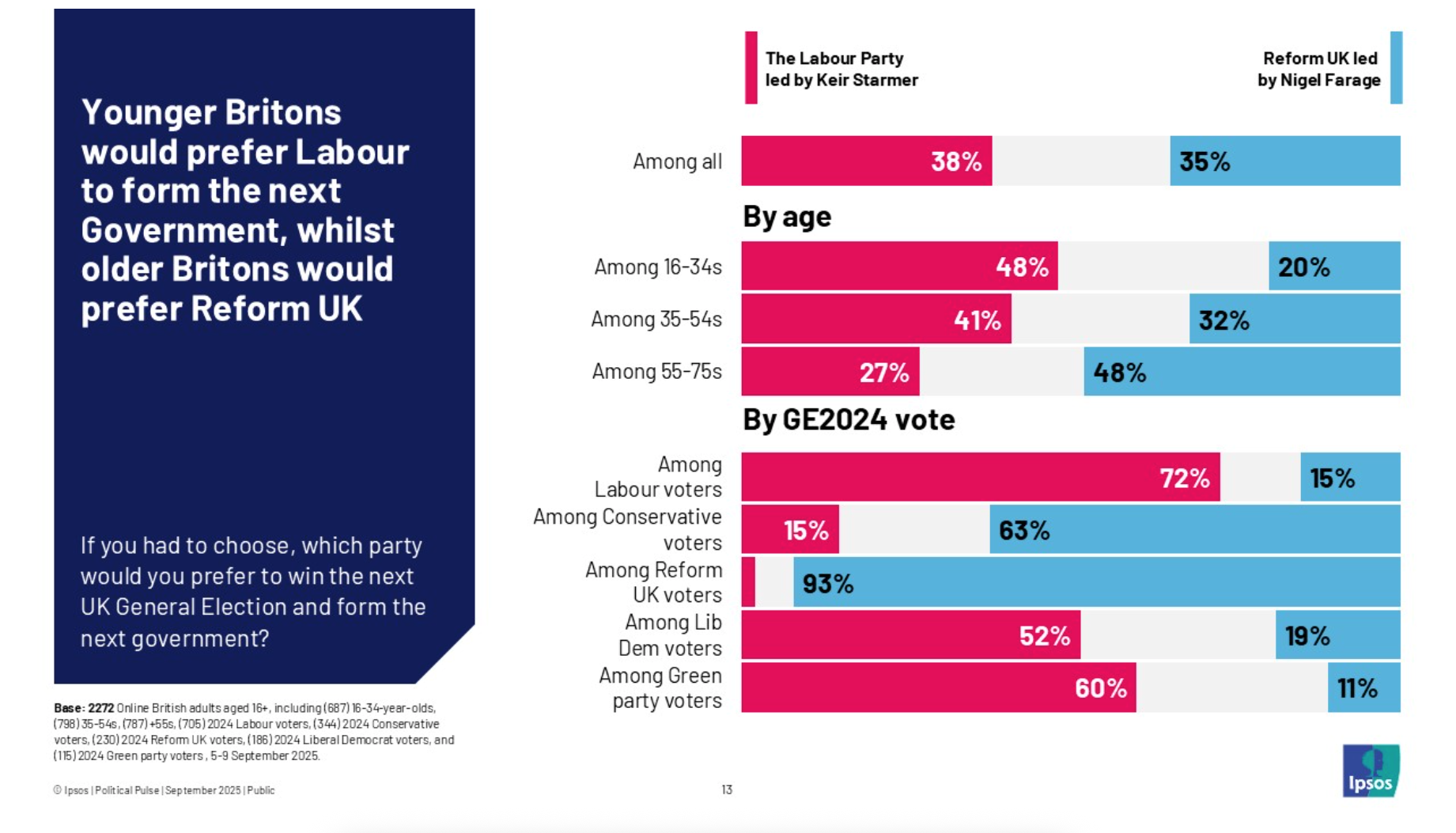

One view is that it looks increasingly likely that the next general election will be a two-horse race between Labour and Reform. People who would like to vote Liberal where Labour has won before will have to vote Labour if they want to ensure that Nigel Farage’s party does not secure an outright majority. The same applies for almost everyone who normally votes Green, except the few Greens that now live in seats with a Green MP. This view suggests that the better Reform performs in the opinion polls in future, the more likely it is that on the day a volatile electorate holds its nose and votes for the party of government, even if they very much do not like this government, to avoid something much worse. If that were to happen, it would require a high turnout from the young in particular, who already most dislike Reform and the racism associated with that party. The second diagram shown in this piece was taken from a report of polling in September 2025.3

So, what is the greatest danger? It could be in making the assumed 2029 general election already a perceived two-way fight between two parties; then support for Reform is further bolstered in the coming years. The danger is that Labour strategists continue to take the issues that Reform voters appear to care most about and try to pander to them, so as to try to hold on to the 27% of voters aged 55–75 years (see the diagram) who they might assume they are most likely to lose in future because of the average and typical views of people of those ages. But that 27% will not be like so many other older people. The greatest danger (I worry) is that in doing so they disillusion more and more of what remains of their existing support, especially among the old loyalists, and do not inspire younger people, who are most likely to be ambivalent, to vote for them.

Ipsos, ‘Britons split on whether they would prefer Labour or Reform UK to win the next election’, Ipsos Insights Hub, 28 September 2025

Ipsos, ‘Britons split on whether they would prefer Labour or Reform UK to win the next election’, Ipsos Insights Hub, 28 September 2025.

Imagine the changes that occur between 2024 and 2025 happening again and again in the three years to come. Those years cannot be as volatile again with as much movement, as that is almost impossible. However, they do not need to be as volatile to be devastating. Imagine a muted continuation of these swings. The Labour vote continues to fall, Reform continues to rise, but at the same time both expressed support for other parties and people willing to say they “Don’t Know” grows. A huge amount changes week by week and month by month in politics. But if what is currently occurring continues, then the hope of a positive change will falter further.

We are in a game of “chicken.” It is a stupid game to play. An alternative would be to try far harder to reduce support for Reform now, rather than assume that the volatile electorate will do “the right thing” on the day.

References

1 James David Griffiths, Ed Fieldhouse, Jane Green, and Stuart Perrett, ‘Looking for Labour’s lost voters’, The British Election Study, 3 September 2025.https://www.britishelectionstudy.com/uncategorized/looking-for-labours-lost-voters

2 Ipsos, ‘One in five Britons would consider voting for a new left-wing party, rising to one in three young people and Labour voters’, Ipsos Insights Hub, 20 August 2025. https://www.ipsos.com/en-uk/one-five-britons-would-consider-voting-new-left-wing-party-rising-one-three-young-people-and-labour

3 Ipsos, ‘Britons split on whether they would prefer Labour or Reform UK to win the next election’, Ipsos Insights Hub, 28 September 2025. https://www.ipsos.com/en-uk/britons-split-whether-they-would-prefer-labour-or-reform-uk-win-next-election

For where this article was originally published and a PDF of it click here.