Is Inequality Inevitable? The ‘Northern European Model’ Suggests Not

The Nordic model of capitalism has garnered substantial attention for its approach to economic and social organisation. While the five Nordic nations – Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden – may initially appear similar, a more in-depth examination reveals great differences both between and within them on a host of indices. The Nordic states remain most similar in reporting much lower than usual rates of income inequality. However, just how low are these rates and how distinctive are the five countries today?

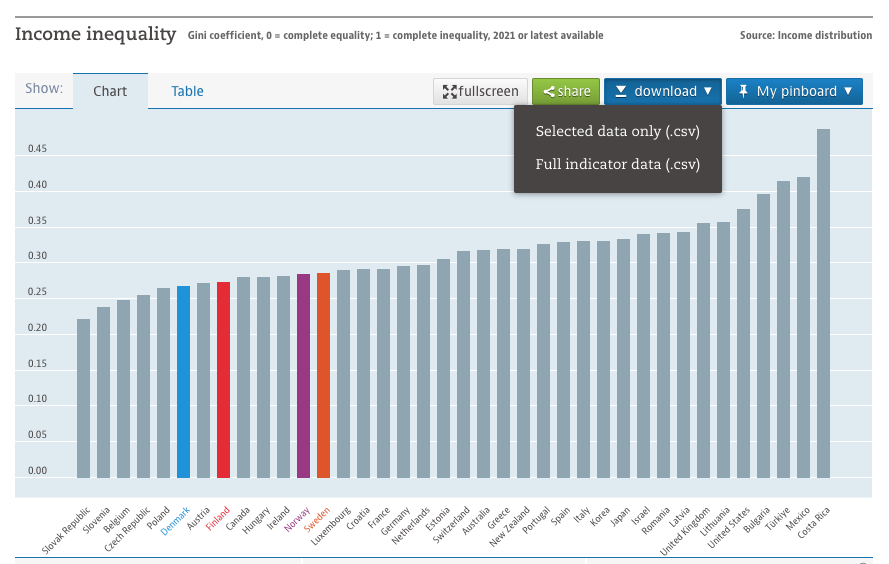

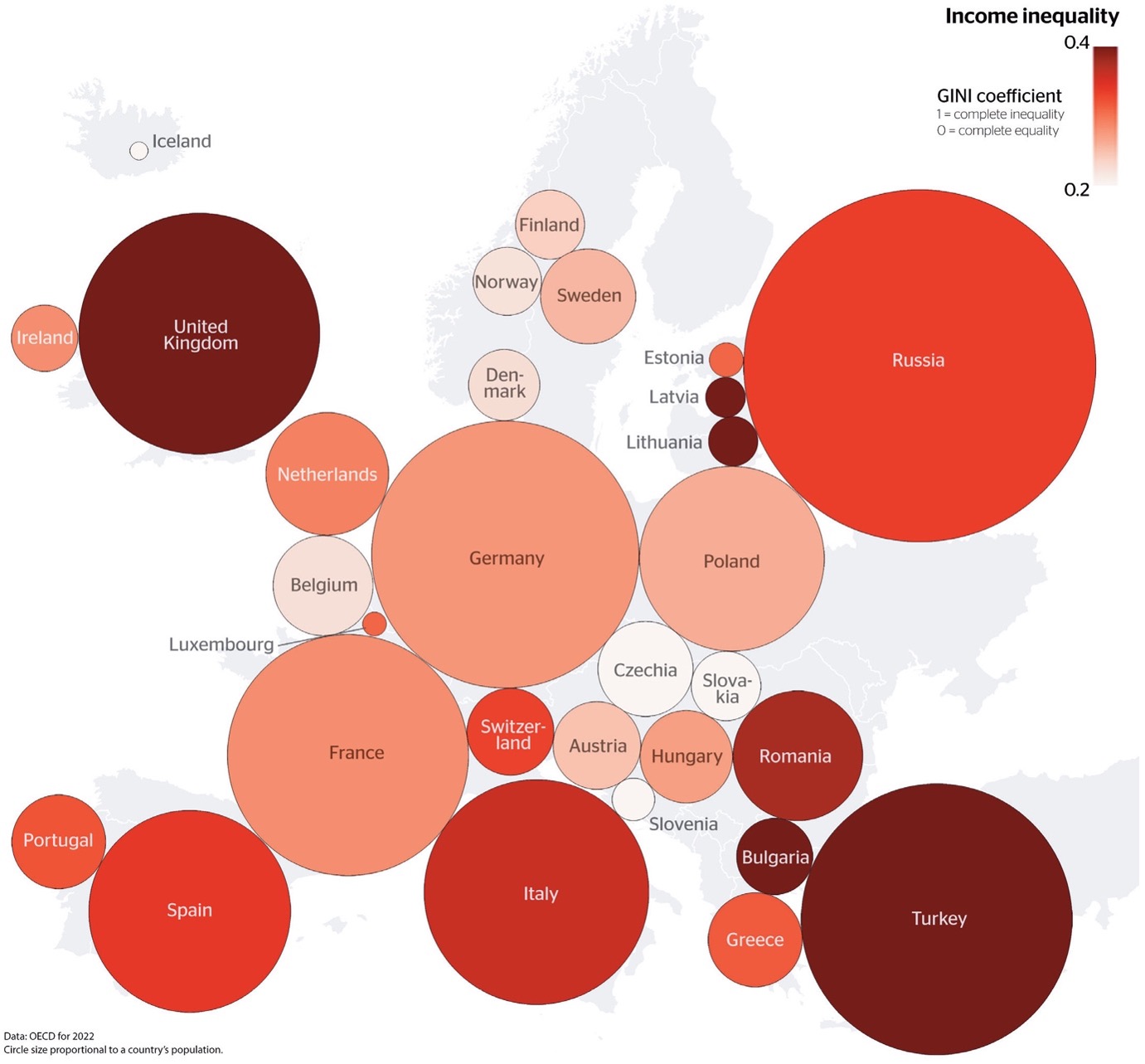

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) provides valuable data on income inequality, shedding light on the economic structures of various nations. Their data shows the Nordic countries clustered together due above all else to low levels of income inequality, resulting in more equitable economic conditions for their citizens compared to many other affluent nations such as the UK, USA, Russia and Israel, which have almost identical levels of high income inequality. However, it’s crucial to acknowledge that the collection of consistent data is predominantly undertaken by affluent countries.

Consequently, when we discuss different models of capitalism, our focus primarily revolves around the affluent world. Here we aim to provide a mainly European perspective. One key takeaway from the available data is the dynamic nature of capitalism. A look at statistics on inequality over a short timeframe may suggest that nothing substantial is changing. However, when we broaden our perspective and examine data spanning from over a longer period, we can observe a different narrative. Over this 14-year period, the Nordic countries appear to have consistently maintained economic equity.

Our timeframe represents just a fifth of normal human life expectancy, a fraction of human history or even of more recent economic history. The Nordic countries cover a small part of the world’s population. Indeed, just how unusual are the Nordics? If we look across Europe we can see another, less cohesive, cluster of nations all exhibiting lower income inequality than the most equitable Nordic country, including Czechia, Slovakia and Slovenia. This prompts the question of why we don’t consider these countries as a similar model or template for a better world.

Differences in shared history and geographical proximity can be suggested, but the latter cannot be the sole explanation, as these countries are just as contiguous as the Nordic nations. In contemporary discussions concerning the Nordic model of capitalism, it is crucial to acknowledge the increasing similarities between these Northern European countries and many other European nations, including larger states such as France and Germany. In terms of income inequality, they are increasingly resembling the Nordic countries.

So, is the term ‘Nordic model’ still suitable? Perhaps we should consider rebranding it as the ‘Northern European model’? The Nordic five are increasingly dissimilar from each other while also gradually becoming part of a broader group of 15 countries, encompassing those slightly more and slightly less equitable. In terms of population, this represents a more substantial grouping, or ‘Nordic+’.

Within the Nordic+ cluster, there are countries that share borders with remarkably unequal states. Immediately to the west of Nordic+ is the UK and to the east is Russia, both characterised by high levels of inequality and challenges for the less fortunate. Bulgaria, the most unequal country in Europe, and Turkey, which is even more unequal and partially situated in Europe, bordering the southeast. These countries also boast outsized capital cities, further illustrating their historical significance as former centres of empires.

Other nearby countries without recent imperial legacies, such as Estonia, Italy, Portugal, Spain and Switzerland, are closer to joining Nordic+ having only slightly higher levels of inequality. Inclusion of these nations would expand the group to a club of 20 countries, making it almost all of Europe.

This discussion also highlights the ever-evolving nature of capitalism. Capitalism is not a static ‘system’ but rather an ongoing transformation, often challenging the human imagination because of our lifespan. The change is over a 400-year period, not within one lifetime.

While some argue that capitalism is a singular concept, it is becoming increasingly apparent that we live in a world characterised by plural capitalisms. These systems share some ideological aspects but exhibit substantial local variations. We are currently in a phase where we are more attuned to these distinctions, particularly between the United States and Europe, where the disparities have grown more pronounced. Growing numbers of people do not accept the story that inequality is inevitable, and in most of Europe they also do not have to live with gross inequality.

income inequality levels in European countries, latest data, OECD, November 2023.

While nations exhibit distinct social and economic characteristics, generalisations are possible. Generally, countries that are closer to the UK and the USA in their economic model tend to be more individualistic, while those farther away tend to be more collective and generous. What is equally intriguing is the increasing resemblance of many countries worldwide to the Nordic model, or in some cases, even surpassing the Nordic countries in various aspects.

The Nordic model is often perceived as institutionally distinct, with higher levels of trust in institutions. However, this trust might have originated from the Nordic countries’ historical equitable and content societies. It is not necessarily that the ‘Nordic way’ is losing its distinctiveness; rather, more nations are embracing Nordic-like characteristics and building new ideas around them.

There are remarkable achievements of the Nordic model, characterised by high innovation and remarkably low rates of exploitation and immiseration. The Nordic model is portrayed as a brief chapter in the ongoing narrative of capitalism, which, in itself, represents a transient phase in the history of humanity.

The Nordic model of capitalism is a captivating case study within the larger framework of capitalism’s evolution. It underscores the intricate interplay of economic and social dynamics, the changing landscape of capitalism, and the influence of global factors on economic systems. Understanding these nuances is vital for gaining a comprehensive view of the complex world we inhabit.

Biographies

Danny Dorling is Professor of Human Geography at the University of Oxford. Benjamin Hennig is Professor of Geography at the University of Iceland and Honorary Research Associate at the University of Oxford.

For a PDF of this article and where it was originally published click here.