The souls of the people of Oxford

Something was done differently on the lands of the University of Oxford during the exceedingly long summer vacation of 2023. Something that had not happened in many a year. Someone, or possibly, a group of someones, made the right call. Our tale concerns river banks, and whether they are crumbling, along with bridges and local participants; including Mole, Ratty, many young swans, and at least one otter. Old Badger was unsure whether it was wise to allow the stoats and the weasels such leniency, but relented. Toad, at first confused over the fuss, slowly came to realise that being seen as aloof, tooting as he passed the lower orders in his car, might no longer be a good look.

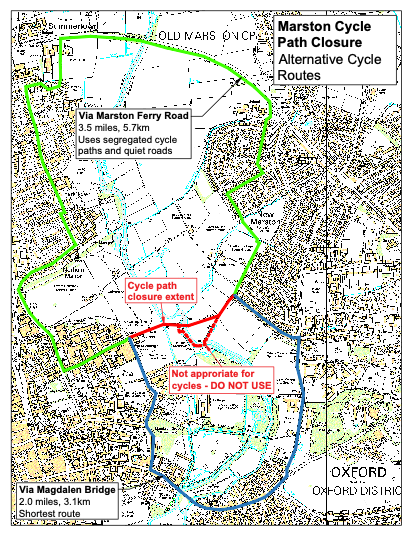

One of the two foot and cycle bridges over the Cherwell prior to 2023 repair.

The events took place not far from the J.R.R. Tolkien bench in the University Parks, and they concerned, above all else, children. What was to happen to the children if access changed?

Children’s stories, when told well, are of jeopardy, suspense and excitement. However, because you are not a child, I will tell you now that this story turns out well in the end. At the least, I hope it does, as the story is not over yet. It continues into the short Michaelmas term, because the bridges it concerns are still shut and the diversion I will tell you of remains in place. It will not be over until a great many years have passed, because it is the part of a much longer story, of how a city and its university changes. Of how ostensibly small things do really matter.

Our story begins many centuries ago, with the seizing of lands, and their dubious transfer of ownership. Its long history concerns the growth of empires and how the most insignificant of river crossings, a ford for oxen became what it is today. But for now let’s skip all those centuries and begin, only 150 years ago, in 1873, when a young man, studying in Dublin decided to apply for the demyship to attend Magdalen College, Oxford. He won the funding and so, in the autumn of 1874, came up to read Greats. His name was Oscar.

In those days it was far harder to traverse some parts of Oxford than it is now, but much easier to move between other parts of the city. To enter the city from the east, if not traveling on the main road, you would travel past the newly built Somerset public house,1 and use the ferry at Marston (marsh town).

To enter the city from the west, if not travelling on the main road, you would have taken a causeway through the often-flooded fields to the Fishes pub, and then used the ferry at the back of the pub to cross the Hinksey stream. Willow Walk would not open until the 1920s, and the route via the Fishes was in disrepair.

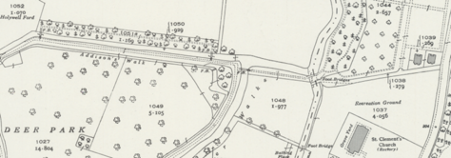

It was a time of renewed public spiritedness. Change was in the air. The Slade Professor of Art, John Ruskin had recently established his School of Drawing and Fine Art. He gained national notoriety, and much later a plaque, when he directed his students to repair the road leading to the Fishes ferry. This was both for the common good, and so that the students should each become a little more individually buff, through exercising their muscles.2

Sign at the site of the public spirited works of undergraduates in Oxford in 1874.

Among the many young men Ruskin enrolled was Oscar, who was a little wild. The high-ups were not amused, and the episode was recorded in the chronicles thus: ‘Most controversial, from the point of view of the University authorities, spectators and the national press, was the digging scheme’ not just because it was encouraging the youngsters to use their brawn, rather than direct the labour of others, but because of what effect such activities had on the young men. The chronicle continued: ‘The scheme was motivated in part by a desire to teach the virtues of wholesome manual labour. Some of the diggers, who included Oscar Wilde, Alfred Milner and Ruskin’s future secretary and biographer W. G. Collingwood, were profoundly influenced by the experience: notably Arnold Toynbee, Leonard Montefiore and Alexander Robertson MacEwen. It helped to foster a public service ethic that was later given expression in the university settlements, and was keenly celebrated by the founders of Ruskin Hall, Oxford.’3

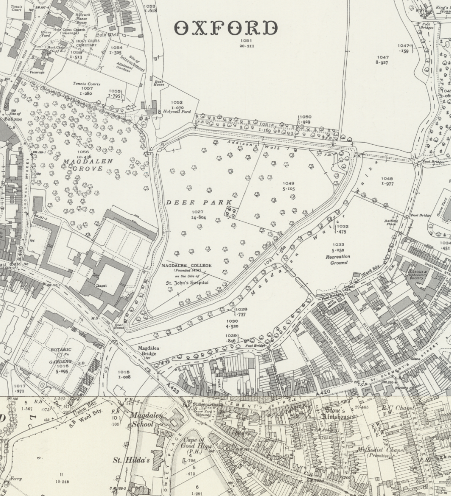

Inset of larger map (reproduced below) showing Addison’s walk and the footbridge behind St Clement’s Church

It can be a dangerous thing, being generous to others. Who knows where it might lead? Once you begin where might it end? Oscar Wilde went on to achieve great things, including writing the essay from which the title of this short story is derived. He was also treated with evil malice. However, Oxford was changing, the country was changing, the world was changing. But why did these fine young men not do their manual work nearer to their colleges? One answer, illustrated by the map above, was that they did not need to. At that time there were public pathways through Magdalen, but, sadly no longer.

There was a bridge across the Cherwell river, not just the bridge that bore the name of Wilde’s college, but dozens of other bridges, and a great many ferries as well. There was a bridge just south of St Clements church (the footings remain today), another just north of the bridge, a third at King’s Mill, a forth crossed from Magdalen School into the land between the rivers just south of Magdalen bridge. Take that route, and then the river could be crossed by two ferries into either Merton’s field or Christ Church meadow. The Cherwell already had a huge number of crossings, which was why Wilde found himself digging out and laying a route for the public to use, in Hinksey.

There was another ferry just 100 yards south again, and many more north of Magdalen College allowing the public to walk across college lands. The penny-farthing had only been invented in 1871, and no one cycled. I would include more maps here, but space is limited. Don’t fear, you can explore the past until your heart is content, by zooming into the wonderful interactive map that the National Library of Scotland now provides, free of charge. Via the Internet anyone can now see how the ancient rights of way cut through the colleges without having recourse to a map library.4 You can change the dates of the map to see when each bridge was removed – because almost all of them, eventually, were closed. Apart from Magdalen bridge itself.

When Oxford became the home of the new motor car, foot and by now some cycle bridges, the punt ferries and public access over college land were mostly consigned to the past. We too easily forget that, before the car, it was the bicycle that made Lord Nuffield his first fortune.

Along with the new cars came buses, which did for the trams that used to run through Oxford. Lord Nuffield was a cunning man and had a financial interest in the buses, but don’t let’s go down that dark track. Instead, let’s just remember that once Oxford had so many bridges and ferries crossing the rivers because people mostly walked and (later) cycled to work along convenient desire lines. Local people continued to mostly walk or cycle in the 1960s and 1970s. The university barred students having cars in Oxford in 1968. Their cars were sometimes made by local men, almost all of whom cycled to work.

The crossings of the Cherwell in Central Oxford, circa 1873

Oxford University was also changing radically in this period. In 1873, Annie Rogers won first place in Oxford’s senior local exam list. Both Balliol and Worcester offered exhibitions (funding) for such an achievement, but not for a woman, because that was against the rules. Rules exist for a reason, to be changed when the time is right. Annie campaigned for open and full membership of Oxford University for women. She won the right to be awarded a university degree in 1920 and became the university’s first female graduate. In 1937, on her way to an evening lecture, she was killed when hit by a lorry on St Giles’.5 She also has a blue plaque.

Annie’s Plaque

Sadly, our story now turns down a darker road. The University was also becoming more insular. In 1908 Kenneth Graham explained what can and cannot be said about such matters: ‘The Mole knew well that it is quite against animal-etiquette to dwell on possible trouble ahead, or even to allude to it; so he dropped the subject.’ I have not the space to detail it here and it may be thought impolite, so it may be best to drop the subject. But should you want to know why the last alternative routes were shut, the bridges closed, and one college even built a moat around its grounds in the 1980s, then turn to R. W. Johnson’s account: ‘Look Back in Laughter: Oxford’s Postwar Golden Age.’ Published in 2015 by the one-time Bursar of Magdalen it triggers a warning for our more enlightened times today. Alongside some hurtful comments about local children in Oxford, it tells of why those public routes over college land were shut to keep the children out.6

Our story twists and turns: there was some progress in more recent times. It was not always unrelenting bad news. Two new bridges, Lemond and Fignon, were built to create a new route to alleviate the harm caused by closing so many public routes through Oxford. Whoever named the bridges (around 1990) had a sense of humour: ‘In 1989 Laurence Fignon, after 3,285 km of cycling and 21 stages plus a time trial, lost the Tour de France by 8 seconds to Greg LeMond. This is the smallest margin in the history of the Tour. And as the bridges are separated by an 8-second cycle ride someone had the whimsical idea of naming them after the two rivals.’7

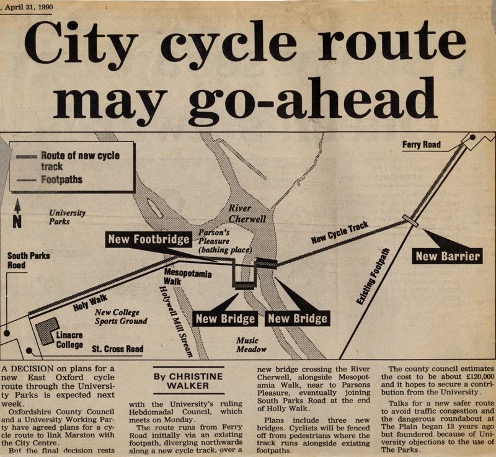

On 21 April 1990 the Oxford Mail announced that an imminent decision was about to be made by the University’s Hebdomadal Council on a new cycle track to be laid across the University Parks with a tarmacked section placed over the River Cherwell meadows.8

The newspaper article ended:

‘Talks for a new safer route to avoid traffic congestion and the dangerous roundabout at the Plain began 13 years ago but floundered because of University objections to the use of The Parks.’

Those talks had begun in 1977. Look closely at the map and you will see that one bridge was originally planned to be set back from the other. This was so that the genitalia of the dons sunning themselves on Parsons Pleasure would not be visible to lady cyclists riding by on that bridge. In the end, nude male-only bathing was brought to an end in 1991 and the path opened with the two bridges aligned. Old Badger may not have approved, but rules exist to be changed.

And this brings us, almost up to the present day. Even in some of the University’s darkest days of closing itself off, the provision of the new track was possible, and the ending of legal flashing by the equivalent of today’s associate professorship was banned. However, after the routes across the colleges and rivers were cut off, new signs began to appear, almost everywhere. More and more signs instructing people to stay out, or if they come into a particular area, to then behave in a certain way. Civility was to be enforced by edict.

In 2022 cyclists expressed their displeasure at the ‘ridiculous and petty’ signs banning bikes in Oxford University Parks. A new sign had just been erected replacing a slightly less offensive one. Below the sign was a notice, printed upon a background of Oxford Blue, and embossed with the University Crest. It informed the reader, standing in University Parks, that ‘CCTV images are being monitored and recorded for the purposes of crime prevention, detection, and public safety. This scheme is controlled by University of Oxford Security Services. For more information call 01865 272944.’

It was kind of them to provide a telephone number, one now spread far and wide by the photographs of the sign ‘going viral’. Interested cyclists from around the world phoned it to ask why pushing a bike was so frowned upon. The Radio 2 presenter, Jeremy Vine, labelled the signs ‘disgusting’. The cyclist who took the photograph reported: ‘this has annoyed me before and it annoys me now. How petty, discriminatory and inaccessible is Oxford University that they don’t even allow cycles to be pushed through Oxford University Parks? Ridiculous restriction in the so-called cycling city.’

Sign erected in the University Parks in 2022.

One commentator did point out that the red circle means ‘not allowed’, and the bar through it means an end to that restriction, so the sign actually implies the end of a no cycling area. Another wondered what would occur were you questioned by a University security official, who presumably had been instructed to give you a sound ticking off should you be found transgressing. What powers did they actually have? To look very upset?

Others did point out that there have been trials to allow cycling in the parks which apparently ‘caused pedestrians distress and it’s nice to have a space just for walkers’. One wonders if smelling salts were made available? The University Parks contain a great many paths, maybe just one could be permitted for bikes to cycle over? However, were that to happen we could no longer pretend that the parks were some oasis of Victorian tranquillity. A relic from a time before the bicycles became commonplace. Perhaps the signs should be altered to permit penny-farthings to allow the charade to continue of trying to pretend nothing ever changes?

And so it was, that nothing changed. The University Parks ban on a bike of any kind, even pushed, remained. Residents of north-east Oxford had only two routes for those who cycle into the city centre: either around St. Clement’s and the Plain and over Magdalen bridge, or along the new cycle path, into Marsh town. Anyone, including children cycling to the many schools from their homes in the South West and West of Oxford were similarly limited. And so it might have remained except that bridges age and fail and new (Swan) schools are built. Thus, many more children began to use the Lemond and Fignon bridges. But suddenly, on July 10th 2023, without warning of the timing, or public consultation, signs appeared at the bridges announcing their closure for ten weeks from mid-August.

Sign that appeared without warning on one of the bridges

Later, in July, a map was made available telling cyclists that whilst the bridges were closed they must either use the Plain, or take a huge detour around the Marston Ferry road; a route which is now saturated with children cycling to both the Cherwell and Swan schools in morning and evening. The map, unsurprisingly, resulted in anger. The immediate question was: who had drawn it, why had they drawn it and who had approved such ridiculous detours?

A map made available later in July

We now know that on the 22nd of June 2021 a man with a hammer inspected Fignon bridge. He had then reported that: ‘There is wide delamination of the soffit which was hollow sounding when tapped with a hammer. A large area of the soffit concrete cover was missing and additional areas spalled off following light tapping with a hammer.’9 A plan began to be made to repair the bridge which would mean an extensive period of closure, but no local councillors and none of the curators of the parks appeared to have been informed. Some in Oxfordshire County Council must have known, but local residents, university students, older cyclists needing a safe route, parents of school children, cycling organisations, were given no warning almost up to the very point when work was to begin.

When the official notices appeared in summer 2023 people began to take notice and offer suggestions. One city councillor suggested that it might be possible to cycle through the red ‘not appropriate route’ (see map above) and appeared to celebrate that if that occurred, that because a gate was involved, at least life would be made harder for those who ride Deliveroo bikes: ‘so this would rule out the bulkier bikes used by Deliveroo and the like – not a bad thing.’ However, appearing to approve of anything that makes life harder for the servants who bring us our food, is not a good look. What various participants thought of others began to become more and more apparent.

And what of the University’s position? It was almost impossible to find anyone who would claim responsibility, but eventually it was revealed that: ‘The Parks Curators have been kept informed of the discussions but have not formally considered any options involving the Parks, as no alternative routes have been determined viable.’

Determined by who? I and many others asked.

Eventually, on August 1st, an FAQ (Frequently Asked Question) sheet was released by the man who had held that hammer in 2021. The FAQ was only issued to local councillors so that they could parrot some stock answers. It was not made more widely available as there was no public consultation. The FAQ suggested that there was an imminent risk to boaters, apparently. Think of the boaters! Who is thinking of the boaters? But are the boaters, on their punts, more important than local people going about their daily business? Apparently so. And thus it was deemed that something had to happen, urgently, although it was over two years since the after the bridge was tapped with a hammer.

Dead willows and the otters

The FAQ sheet was written in response to a local resident’s suggestion (made and ignored) that a pontoon bridge could have been placed just south of Lemond Bridge to land on Mesopotamia in an area of scrub with no trees affected. Apparently every tree, unlike every child, is sacred. Those installing the pontoon bridge would have to be wary of the dead willow, one which by August 2023 had been unsafe for many months with a heavy branch hanging by a slender sliver of wood. The dead tree was clearly just as dangerous to boaters as the decaying concrete under the Fignon bridge. Neither the University, Environment Agency (the successor to the National Rivers Authority) or the County Council had shown any interest in dealing with the dead willow.

Advice from the City Council’s Wildlife Officer mentioned otter sightings, stating that providing that the lower arm of the river along Mesopotamia was kept clear and free for wildlife, then the threat to otters in and around Parsons Pleasure would be alleviated. No otter nests had been found within 150 meters of the bridge work (which could have been a serious constraint on the way the works were handled). So wildlife threat was not a good reason for not building a temporary pontoon bridge. The temporary route would lead straight onto the bridge into Music Meadow from Mesopotamia.

Ben Dodds

Principal Engineer | Oxfordshire Highways

Milestone Infrastructure

Companies that provide temporary pontoon bridges specifically state that their bridges can be suitable for mass gatherings such as festivals. They can deal with large crowds and heavy loads.

A suspicion grew that the project manager for the bridge renovations working in County Hall but employed by Milestone Infrastructure, through an out-sourcing contract with the local authority, had not thought through any of the problems or alternative options that could arise from closure of the bridges for an extended period. Almost inevitably, a commercial company puts profit above public utility. It seems that this has happened here. The project manager had a desk in County Hall, but when asked by a member of the public whether he was a local government officer he categorically denied this, saying that he worked for the private sector.

Oscar Wilde might have a thing or three to say about Milestone Infrastructure and this behaviour. Thinking this through, and coming up with a sensible and safe way of dealing with disrupted cycle traffic, would have been harder work. It was what this private company’s employee was saying which resulted in the University administrators claiming: ‘no alternative routes have been determined viable.’ The buck, it turned out, stopped with the project manager, who was also the man with the hammer in June 2021. Or did it?

On Friday 18 August 2023 the cyclists of Oxford added their voice to the clamour from local parents, as well as those concerned that elderly cyclists were also being directed to the Plain. The cyclists were concerned by a ‘too long and too dangerous’ diversion as the cycle path was closed. They were upset upon learning that ‘Oxfordshire County Council says it had “no choice” but to close the route for bridge repairs, but some have questioned why a “safe” diversion has not been directed through University Parks, with it instead visiting a notoriously dangerous roundabout…’10

The cyclists reported that the most damming of English words had been invoked and someone was – I almost dare not write the word for fear of shocking you (trigger warning) – ‘disappointed.’ A city councillor invoked this damning condemnation: ‘I’m very disappointed that, after six weeks of discussions with the university, county council and local residents we have been unable to find a safe alternative route across Marston Meadows’.

Things became a little heated. Who was it that had acted on the man with the hammer’s advice? Were they willing to stand by it should a child die on the Plain on their way to school? That was the obvious implication of all the questions being asked. The atmosphere became a little unpleasant, but fear not, loyal reader, for here our story finally begins to take a turn for the better.

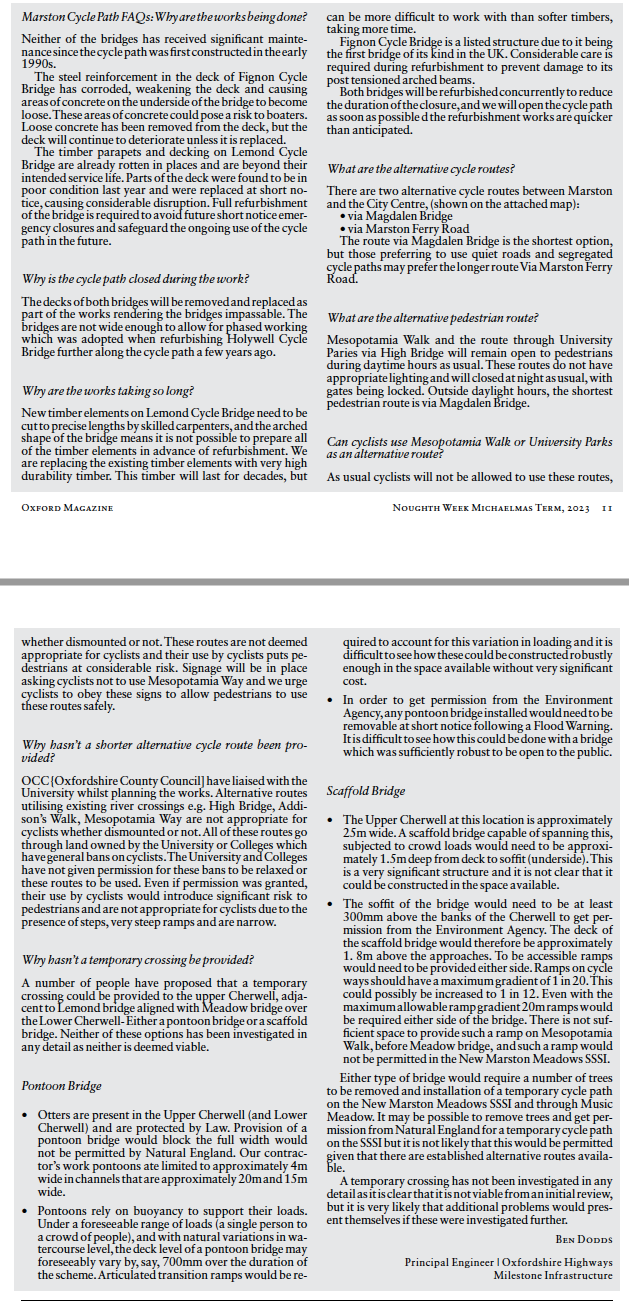

Committees don’t sit over the summer, someone, somewhere made a decision all by themselves to do the right thing (or a small group of someones). Or, to be more truthful, to make the smallest of possible concessions when the heat of this somewhat tortured tale, became too hard to bear. Someone realized that it is the University of the city, not that the city exists to serve the University. And that anonymous someone gave permission for Andrew Gant of the County Council and Alexander Betts of the University to issue a joint statement.11 Thus it came to be, that exactly a month after the FAQ had been issued, and within days of the schools opening, on the 1st of September 2023, Oxfordshire County Council issued an official notice, on their website. And a new word entered the lexicon of instructions in this tangled tale, a softer word: ‘urged’ – see if you can spot it in the text of the statement below.

One councillor reported: ‘The University reserved the right to pull this diversion if it’s not working, if we can’t get the marshals (or, unlikely, it’s not used). So people are encouraged to volunteer’. This was accompanied with messages such as ‘will hopefully be a jolly experience for those who take part.’

Why were marshals needed? Why were cyclist being urged not to use the now pink dashed route (formally red) on the map below?

Apparently it was because ‘the river banks are very unstable and risked people falling off them into the river as they are not very wide’. My chair is named after a man who once climbed a mountain. It was time I manned up. I knew my duty and so got out on my bike and cycled the pink route. In the spirit of past great explorers entering lands without the appropriate permission, I set forth on my bike.

Andrew Gant of the County Council and Alexander Betts of the University issue a joint statement.

Geographers, of which I am one, have years of training as regards rivers. I have endured the most terrible of horsefly bites while standing still holding a measuring rod in rivers in more than one country. I am, amongst much else, something of an expert on river banks. And I can report that the river banks are not unstable, that you are a very long way away from the river when cycling on the route, and that you would have to try extremely hard to fall into the river. If you are interested in doing that (falling in) then cycle along the cycle path next to Oxford canal, you will find yourself much nearer to water and in much greater danger of falling in. Here, I am not suggesting preventing cyclists from using the canal path, just take it extremely carefully and slowly. And if you want a narrow cycle path – there are many in Oxfordshire far narrower than this that are shared by both bikes and people. But it is the contractors to the county, employed by Milestone who are the ultimate authority on river banks in the city of Oxford today.

The ultimate ownership of Milestone appears to be vested in French private finance multi-millionaires. This company had been sub-contracted by Oxfordshire County Council to carry out their responsibilities, just as the University has in effect, subcontracted its responsibility to ensure a safe well-maintained set of paths into Oxford to the County Council, while retaining ownership of the land. Everyone thought they could sub-contract their responsibilities away. And so the man with the hammer ended up taking the heat. A colleague wrote to me ‘Maybe I haven’t misunderstood this, but sometimes I am ashamed to be part of this university.’

But this story ends well, the marshals appeared, enter the Oxford yellow vests. Sporting their best gilets jaunes (blanche and orange for two stylist dissenters). Five marshals appeared on the first day, and maybe another five on the second. The last time I pushed my cycle along the new Oxford blue route (map above) I only counted two marshals – but let’s not tell the University that. It can be our little secret. On 19th September, following a meeting of the Parks authorities, marshals and councillors, a decision was made to extend the time for using the alternative cycle route through the Parks by half an hour. More importantly, the Park authorities are engaging with others.

Oxford’s yellow vests – those who first marshalled the safer alternative route.

I guess the marshals were required to maintain the Victorian ambiance of the parks – a Victorian park comes with Victorian style marshalling and Victorian attitudes. Someone somewhere really wanted to get the children to get off their bikes and pushing them – even if the alternative is to cycle round the Plain; which becomes a faster route once you require the children to push their bikes through the Parks.

I decided that I would rather not know who that person was, so did not ask.

Previously I had sent hundreds of emails over the summer to try to determine who was responsible, and then plead with them to take action. I was far from alone, I had a vested interest. My nephew cycles that route to school. My youngest son cycles it to serve wine and carry plates of food in the evenings at a college, his only alternative would be the Plain.

In some of the replies I received I detected something I had felt before, as an Oxford child, and later on first arriving back in Oxford over a decade ago but never had the language to describe. I have that language now: The Oxford sneer – the curled upper lip – the sneer has a particular quality to it in this place. It may be subconscious, but it occurs in written communication as much as being a facial feature you might find hard to control. It is less useful, less attractive, and far less well known than the Oxford comma. But it definitely exists. Those who claimed an alternative route for cyclist was needed won out, despite others sneering that none of this was needed. I asked questions (by email) that revealed just how little they knew of the city they lived in. I kept the emails. I always do.

On the 14th of September 2023, former city councillor Roy Darke, one of the most effective campaigners to ensure that the University was not too stupid, had a letter published in the Oxford Times. Its text reminded me of Utopian stories of successful urban design in which the old will look out on children playing, with parades of perambulators being pushed by, young men and women passing merrily, alongside the cycling old maids on their way to evening mass in the autumn mist, and those in wheelchairs also well accommodated. But it also offered up a new vision, or rather a modern vision, of what we once had long before any of us were alive, and how we might win that back again – more active travel routes across the rivers and into city:

‘It is with pleasure that I sit eating breakfast on Edgeway Road and see youngsters (and others) cycling safely in and out of town on the safe ‘alternative route’ whilst the bridges are renovated. But let’s not be too complacent or sycophantic about this temporary reprieve from the fatal and only alternative route offered for cyclists by the County Council. Requiring 11-year-olds to cycle to school via The Plain was downright irresponsible and showed open neglect of public duty and a lack of spirit and imagination.

The University and local authorities should more openly take joint responsibility for making Oxford a safer and more equal place. A safe city means looking to create more vehicle free routes for cyclists and pedestrians. A series of Calatrava-style cycle bridges across Magdalen (Addison’s Walk), Christchurch Meadow (linking to Meadow Lane), through LMH etc. would add enormously to cycle safety and excite the aesthetic scene in this inspirational city.’

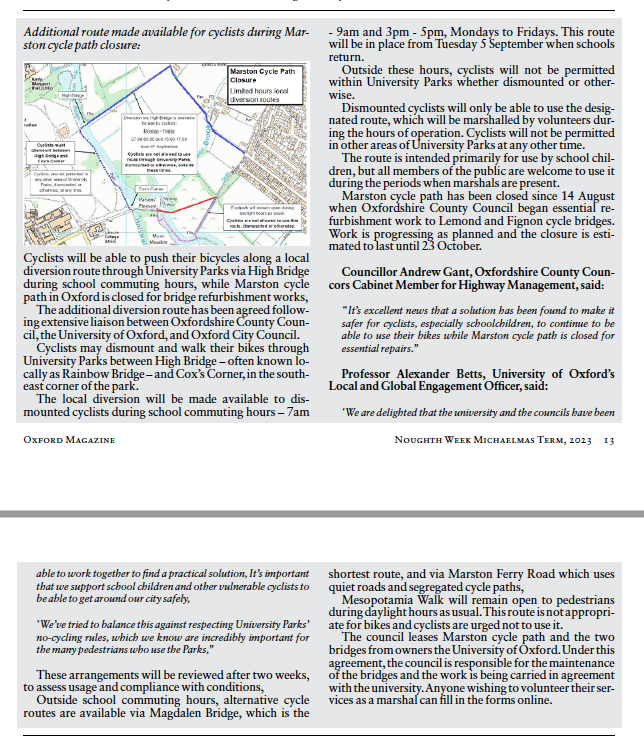

There are many different Calatrava style cycle bridges to be seen all around the world. Most are short and subtle, but some are large enough to span the Thames and allow shipping to pass. One is shown here.12 We are a long way behind the Dutch (in so many ways, including, when it comes to travel), but there are many ways in which new bridges can be built. As well as new platforms across meadows, over steps, and through Fellows’ Gardens.

A Calatrava style bridge – in the Netherlands.

Like Newcastle and Gateshead have now across the Tyne, and Oxford once had, there should be again seven bridges, cycle and foot, across the river Cherwell. We should have so many ways to cycle that when one route needs to be repaired it causes no problems. Far better to donate money for a bridge to save lives, than for yet another university building that doesn’t. The many colleges that border the river could all have a bridge for cycles and walkers, or make the existing ones open. Since I have returned to Oxford in 2013 the only new bridges that have been built were two, both built to ensure that students (unlike Oscar Wilde) would not have to mix with the public.

If you don’t know by now, why all this has to change, and why this is not the end but only the beginning of a story, then think of what happens when everything changes, forever, with no trigger warning. Don’t think of the child necessarily, or of the old lady who gained the first degree cycling across St Giles, on her way to an evening lecture. Don’t think of the mother of two, or the husband, wife, boyfriend or girlfriend. And don’t necessarily think of those school children. Instead think of their parents, their friends, their siblings (like me), and their children, their partners, those who live with what happened for the rest of their lives; and – if you can, think also of the drivers. When a car, or bus, van, or lorry hits a cyclist hard – without any trigger warning – everything changes, forever.

On the 28th of April this year the BBC ran a story featuring Ling Felce who was killed when she was hit by a lorry on 1st march 2022 on the Plain.13 The story was about how just one extra incremental change was being made to the design of Oxford’s still most dangerous roundabout. Lorries were to be banned from loading and unloading goods between 7am and 10am and 4.30pm and 7pm on or by the Plain. But what happens outside of those hours? What will happen when the next University scientist dies on the roundabout?

Ling Felce

Ling Felce’s husband has spoken out, including to the BBC, about thinking of the family of the vehicle drivers –which is very admirable and something rarely seen in public.14

The County Council, as the democratic planning authority, needs to establish a review group to reassess cycling in the city. Its aim should be to ensure no road deaths of cyclists, of pedestrians, of drivers or passengers (vision zero) and that far fewer are injured every year. The colleges, the University, the city and county local authorities need to work together to establish safe connections between all the University’s sites, the city’s schools and homes. The University itself should employ a cycling expert to coordinate action for safer cycling throughout the collegiate university, and to work closely with the local authorities so that the university, and especially the colleges, are helpful – rather than being a hindrance.

Finally, the Cycle Track and Mesopotamia are always closed on 25 December and 1 January. Do we really want to increase the chances of a death on the Plain on Christmas Day because we are so scared of re-establishing what was once a nearby right of way?

1 http://www.oxfordhistory.org.uk/streets/ghost_signs/breweries.html

2 http://openplaques.org/plaques/3780

3 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Ruskin

4 https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/side-by-side/

5 http://www.oxonblueplaques.org.uk/plaques/rogers.html

6 http://www.threshold-press.co.uk/memoir/r_w_j_laughter.php

7 https://www.cyclox.org/index.php/2023/09/07/cycle-path-diversion-through-university-parks/

8 https://www.headington.org.uk/maps_transport/cycling.htm

9 https://docs.planning.org.uk/20230220/8/RPQATDMF1BN00/fz1y1oy4yo0so53k.pdf

10 https://road.cc/content/news/cyclists-concerned-dangerous-diversion-303347

11 https://web.archive.org/web/20230903095124/https:/news.oxfordshire.gov.uk/additional-route-made-available-for-cyclists-during-marston-cycle-path-closure/

12 https://inhabitat.com/arching-melkwegbridge-routes-pedestrians-cyclists-across-a-canal-in-the-netherlands/

13 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-oxfordshire-65423191

14 https://www.roadpeace.org/prevention/

Danny Dorling is a patron of RoadPeace, the national charity for road crash victims in the UK, and the brother of Benjamin Dorling (1971-1989), who was killed by a car when cycling on his bike, coming home, in Oxford.

For where this article was original published and a PDF of it click here.