When we were young: Inequality revisited, a commentary on Geoffrey DeVerteuil’s essay

Not very long ago, the world had a different shape. The cities were shaped differently too. Anglophone geographies brought into life theories about what all this meant. Global Urban Studies was a little prince world. A world in which each prince, each scholar, created their own theory. Theories were plentiful. In Le Petit Prince the Geographer is ‘…too important to go wandering about. He never leaves his Study.’(1) He believes that geography books are ‘…the finest books of all. They never go out of fashion.’ The geographical scholar (who Antione de Saint-Exupéry had brought to life) distained the ephemeral, that ‘which is threatened by imminent disappearance.’ That particular little prince world is no more. The 1990s theories turned out to be ephemeral. Geoffrey DeVerteuil’s essay breathes a little life back into some of them, arguing for not forgetting – not becoming too distracted by the new, especially not by the more obviously ephemeral ideas that often dominate today.

In times within living memory, we talked more about class. It was class, we said, that shaped our cities. City structures reflected our class hierarchy. Flat corrugated iron roofs were the symbols of poverty. Roofs that barely kept out the rain and held in no warmth. Grand homes with high-pitched gables displayed affluence, projected authority, and gave material comfort.

Billions grew up under the deafening sound of the rain on iron. Others, little princes, were driven in cars past those ramshackle homes in their childhoods. They glimpsed lives they could only barely envisage living themselves. They learnt not to imagine. It was the city of walls, of quartz, of iron roofs and townhouses.

The squeezed middle was shrinking. Increasingly, you were either privileged or poor; prince or pauper. The city used to be more corrugated. The elite ridges separating everyday valleys were of lower social elevation in that past. The working-class grooves between them, were higher. The undulations, are more closely packed.

Back then, rich lived nearer poor. But the middle was slowly squeezed out as inequalities rose. Back then, rich were less rich and poor less poor than now. Society, though, was being stretched thin. It was, increasingly, those with more princely childhoods who were writing the new theories. There was so much more to the story of inequality, they suggested. principally, that they had so often, more often, been brought up set apart by money was not of most importance anymore. The princes were aware, they implied, of their positionalities; of their privilege.

DeVerteuil’s analogies of corrugated and lopsided are apt. Today the city is more lopsided. Gentrification has now filled up the gaps between a few of the highest hills of wealth. Proletarianization has levelled down other parts of the city. Now the city looks more like a giant volcano than a series of flattened low-lying valleys. A lopsided volcano with steep cliffs.

The once corrugated city is no more.

Today the very richest little princes own the townhouses, maybe more than one, but those dwellings are now worth so much more than before. In increasingly unaffordable enclaves, in almost every city, the grown-up children of the rest of the rich colonise the tiny homes of those that were once poor. Refurbished at great expense, these residences are named after French jewellery (‘bijoux’).

Said to be worth a fortune, bijoux homes are increasingly purchased for show and because of the princes’ growing fears of living elsewhere. Supposedly a safe investment, they are places where most of their value is derived from being high up on the cliffs of the volcano, up far above the poor. Their purpose is not to display affluence, project authority, or give great material comfort; but to be safe spaces. The princes think they live in modest homes.

As the city became more lopsided, concerns on the cliff sides transformed with the rising up of the social cliffs. To princes, those with the least began to look more like ants, no longer so human, as others are now so far below. Children who had learnt not to imagine being poor, began to see themselves more often as suffering too, in an increasing variety of ways.

You may inhabit a jewel of a home, a bijoux home, but now you too can be just as much a victim of inequality in the new lopsided city.

Today, little prince, your gender, race, sexuality – or one of many possible disabilities and neurodivergences – increasingly matter to your life on the cliff side. Your grievances, you are told and begin to tell others, are of equal importance and deserve as equal respect as any other feelings. Whether as a child you slept on silken pillows or under a corrugated iron roof is just one aspect of your fascinating individual identity.

In London, in 2023 candles began appearing again in the rooms of homes at the bottom of the cliffs. Homes in which the paupers can no longer afford to feed the electricity meter. In Baltimore, and across the United States, is it no longer unusual to have known eviction as a child. In my home city of Oxford, the poorest babies are again being brought up never having been washed in warm water. The fuel prices rose too high in 2023 and in the year before.

As yet, it is only a few who suffer the worst extremes of this new pauperisation in the richest of countries. But it was not like this in the 1990s; and it is all now taking place under the shadow of the princes’ homes, under the shadow of streets ‘worth’ billions. There are far worse stories to be told from the periphery of the United Kingdom, and much worse from the most shattered badlands of the United States.

It is the lopsided nature of the suffering that most grates. The rich, in a time of fuel inflation, do not know how high their heating bill is; they simply pay it. A few also pay the heating bills for their stables and swimming pool, their second, third and fourth homes, and perhaps for their garage too, to keep the car warm.

In Buckingham Palace, a prince who recently became king, turns down his thermostats. But he does it because he cares so much about the planet and he worries, like Antione de Saint-Exupéry’s creation did, about the future of a flower he holds in a pot in his hands. The planet matters more today, and the poor matter less. He wanted to be a defender of all faiths, not just one. Intersectionality matters to him too. He would never ask a guest where they were really from.

This kind of inequality – new extremes of poverty and riches coupled with greater sensitivity for other differences – is today just one inequality among many in our newly more lopsided world. All inequalities have become of near equal importance: racism, misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, and the recognition and respect for a myriad of forms of your and others’ neurological different strengths and challenges. But if, little prince, you can claim to suffer from more than one of these prejudicial victimisations, that intersectionality is of greater importance.

Suggest that racism tends to disappear when and where inequalities in income and wealth narrow, and you, little prince, might be greeted with derision and the accusation of not taking deep-seated prejudice seriously enough. Suggest that at the heart of misogyny is an inequality in power, and that above all else it is money that confers power, money that lets some people buy other’s time and lives, and that might imply that you just do not understand and empathise enough with the other, or understand affect and that you concentrate too much on the material. Point out that violence against trans people is disproportionately suffered by those in poverty, particularly those in forced sex work, and you may be suspected of belittling the harm caused by micro-aggressions.

More people in your city may now be hungry each day, but hunger has become just one of many possible sections of a greater intersectionality. As today’s scholarly geographer might observe to a visiting little prince, such distinctions are most commonly (and increasingly) made in the two countries that are home to those who contribute most to geography and urban studies journals. It is where hunger has grown the most in the rich world, where income inequalities have grown highest, that class has been most demoted to now become just one inequality among others.

As the paper that this commentary addresses makes clear, concern for intersectional thinking has become most common in the ‘more neoliberalized contexts such as the United Kingdom and the United States’ (DeVerteuil, 2023). And hunger and poverty of others are now seen as being of greatest concern in places where hunger has become most rare, in the least neoliberalized contexts, in the most equal of affluent nations.

In the 2020s hunger is most rare in the Nordic states and in Japan, France and Germany, in those countries where culture wars are less dominant; where the cities are far less lopsided; and where the poor have more power, still the least power, but they are not as comprehensively so often ignored as they are by today’s Anglophone geographers and avant-garde global urban studies scholars.

Acute poverty is accepted as a part of the new social landscape in the risk-taking U.S./U.K. context. A new arena where what increasingly matters is the multidimensional imagined playing field of opportunities to be made more equal. The fields in which the little princes play.

Among today’s young princelings, those most awake point out that if 16-year-olds can join the army then – if a child is old enough to consent to murder people for their country – they are old enough to know their own mind and arrange for their own medical operations concerning their own gender identity. You hear such arguments less often in the less neoliberalized states.

Yesterday’s young, who were awake, suggested that it was wrong to travel abroad to murder people for your country, whether you were a child or not, whether you were conscripted or had volunteered. They wore flowers in their hair and dreamed of a future in which one day their grandchildren would walk hand in hand.

So much changed in such a short space of time. What was it that transformed the corrugated city to be so lopsided, especially in the homelands of the theorists? Perhaps it was the fastest international growth over time in income inequality being in the United States and United Kingdom? Maybe that lies behind this shift from anti-war protesting to arguing that being permitted to kill is a valid reason for a child determining for themselves whether to have a life-changing operation on their genitals?

It was only a small minority of the old that marched against war and cared so much about the 16th of March 1968 Mỹ Lai massacre. Did the marchers succeed? Do you know of that massacre?

It was just a minority of their children that rallied against growing inequalities in the United Kingdom and United States in the 1990s. They certainly failed. But do you know of their failure or was that just part of so many other battles, all of equal importance?

So, too, it is only a small minority of the young, of the grandchildren of the hippies, arguing that what they think of what lies directly beneath their own navels is one of the most important issues of the day – and it might be. The old often resort to saying it is too early to know.

The lopsided city is a city of growing grievances where the old among the affluent still worry that the pitchforks are coming for them, while their children complain that their parents simply do not understand their problems. All the while, the poor look up bemused, necks craned ever more painfully in the ever-shortening spaces of time they have, between jobs, to contemplate what is happening high up above them.

The poor say of those with power: ‘they are all the same’. Which is worth bearing in mind when thinking about the growing myriads of inequalities now widely recognised within rich families.

What do people argue about in multi-million-pound townhouses? What intersectionality of class, culture war and generational difference matters most to those who do not have to worry about hunger, heat or cold? In the lop-sided city, the debate within these palaces is amplified by what has come to be called social media, which is the platform little princes use to project their views.

You might take great offence at what you see as your right to exist being debated. However, if more and more of us princelings take offence at anything we see as infringing our chosen identities, we will end up spending much of the rest of our lives taking offence. Proclaiming our offence can ever so easily offend other little princes, so we start to dance with our words.

Grow up as an affluent child in the lopsided city and, as an adult, mention your concerns over the comments of others and you may be less aware than, less awake than, and less conscious than the children of the corrugated city are in how badly thoughts can land. Complain that you ‘do not have a right to exist’ because not everyone agrees with your ideas on gender identity, and you probably do not notice the wry smile of the old person whose parents and grandparents were denied their right to exist through the gas chambers. Soon, none of that generation and their memories will remain.

Similarly, claiming that others need to understand that you are the ancestor of one group or another that suffered greatly and that your group’s suffering in particular must be especially revered, can cause offence today too. It is easy to not notice the slight rise of an eyebrow (when you talk of your ethnic suffering) of someone differently descended for instance from so many generations that were enslaved, raped, tortured and killed, such that it is now impossible to count all their tens of thousands of direct ancestors that were slaves – those who suffered for centuries, those from whom their genes come – from the survivors, the living dead, who toiled under the hot sun in just one tiny sugar island in the Caribbean.

Be socialised in the lopsided city and you are so much more likely to see yourself as the marginalised person, the centre-point of injustice. Your talent and individual hard work, you may believe and suggest, is being held back by others who do not respect your feelings enough. You are a part of what DeVerteuil describes as the ‘…greater (and long-overdue) interest in other axes of difference in the city – gender, “race”, sexuality, disability’ (op. cit.). Overdue, this multi-dimensional space of positionality may be, but its advocation hardly ever comes most vehemently from someone without privilege themselves.

Class is now seen as just one of the many axes of inequality, one that there are less and less attempts to reinvigorate. Often today, high up on the cliffs, it is seen as enough if you ‘respect’ and ‘feel for’ those not as privileged as you. Woe betide anyone suggesting that inequalities which result in one group living shorter lives than another are those inequalities which matter most. Especially if the person making that suggestion might quip about knowing your privilege.

A more material account, based on empiricism, might suggest that trans matters most because of the suicides; it would result in a hierarchy of racism which can be measured by whose lives are lost youngest today. This would be a hierarchy that differs in different parts of the world. This would be a counter to the conservative vanguardism that declares that all identarian inequalities are of equal importance. A more material account might emphasise more that it is where women lack socioeconomic capital, or put more simply money, that they are most vulnerable to domestic violence, lack of access to reproductive care, and hunger.

The right to exist is denied, most obviously, to the infants who are born but then very quickly die in that very populous state in Europe with the sixth worse neonatal mortality rate in what was the European Community – the United Kingdom.

The right to exist is denied to more new-borns in the United States, than in anywhere in Europe. Poverty in motherhood and material mortality matter far more than deciding whether it is appropriate to use the word mother, at least to an empiricist.

Within the princelings culture war in the lop-sided city, there has been a displacement of the empirical. The irrelevance of empirical data, of questions over how many people might be being harmed and how badly, is the only thing both sides of the culture war agree on, although the right sometimes plays with data to goad the left. And while their own longevity and personal health and well-being are becoming central concerns of today’s princelings, that of others is mentioned less and less – especially in those disciplines and countries where fashion has most moved towards becoming academically lopsided.

An empiricist might suggest that the disabilities that matter most are those that cause the most ill health and ultimately early death. Grieving parents of dead children matter as much as they ever did, but now have to compete for sympathy with the feelings of others over perceived slights that can only often be taken so seriously because there is so little other suffering high up on the cliffs.

Longevity is not everything, but people, rich and poor alike, worry the most about health in the long run and especially as they become older. All these things can be measured. Grandparents worry most about the health of their grandchildren – often more so even than their own health, and sometimes more than even parents do. We are social animals, shaped to care for others as much, if not more, than ourselves. But in the lopsided city that innate disposition is subverted, replaced with an ever-greater concern about me, me, me.

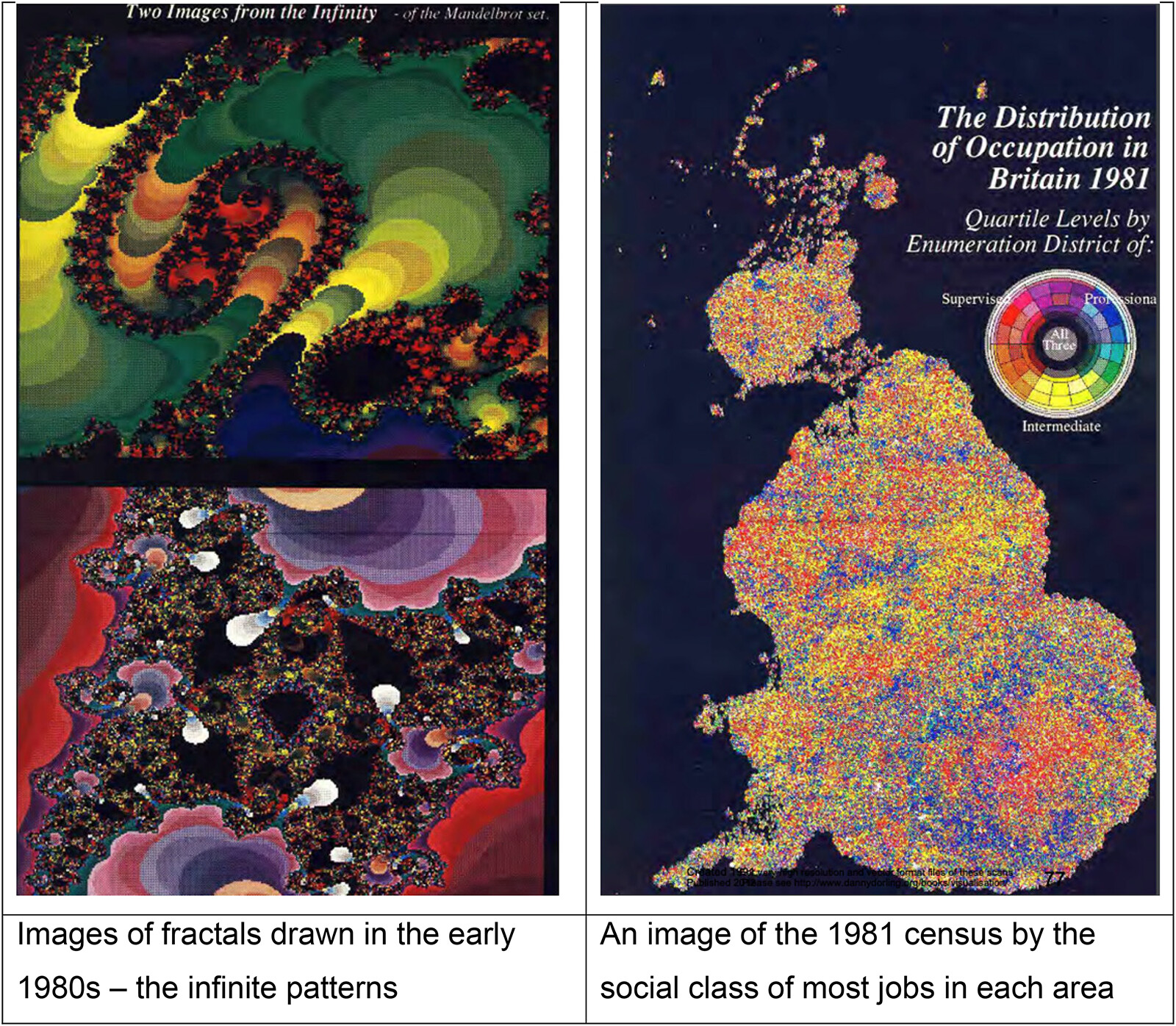

Fractal encapsulates the corrugated city; a particular mathematical pattern. If looked upon without feeling, without thinking about what it is that is being shown, the fractal pattern of the corrugated city, of the geography of social class, is beautiful – and almost infinitely corrugated. It is the image that best represents the reality that ‘In the corrugated city, the extremes of the city fabric relate to each other in a rough balance’ (op. cit.). Figure 1 shows a pattern of intricate corrugation drawn from the 1981 census of the United Kingdom, the map, a population cartigram of over 100,000 areas, is to the right of two of those first computer generated images of fractals.

Beneath Figure 1, beneath the surface of 1970s and 1980s census maps, the first ever to be drawn in great detail and in colour using computers, are patterns of great injustice. Then there is what the censuses cannot count, the unmapped patterns of informal 1990s economies, of rising sex work, cocaine dealing (most common in London), wrapped fractal-like around the formal economy of finance and booming after the Big Bang when bankers’ pay exploded. What appears fragmented is often actually fractal. The poor are poor because the rich are rich and both groups are wrapped tightly, geographically, around each other.

Without human cartography, without images, you do not have maps of who is inside each dwelling. The buildings’ exteriors cannot tell human stories, yet there is a renewed fashion for suggesting they can. In contrast and when we were learning more about ourselves, the first maps of poverty, of Manchester and London, were drawn by the sons and daughters of the rich. Without empiricism, today’s scholars in the lop-sided city are left gasping for words. They imagine their reader sees the same thing as they do in their own mind’s eye: ‘unequal and fragmented materiality’ to be ‘visualised via juxtapositions’. What do they mean?

The imaged Blade Runner future of the lopsided city cannot be envisaged simply by viewing the outsides of its buildings. As DeVerteuil explains, the ‘lopsided city is where the powerful few hold increasingly disproportionate power over the majority of the urban population, an extreme version of inequality and unevenness that suggests one side is winning (but has not won entirely yet). This contrasts with corrugation, which suggested that the middle is losing out equally to the extremes at the top and bottom’ (op. cit.).

Stories of extreme inequality best fit the United Kingdom and United States; fit less well the rest of North America, much less so almost all of Europe. Mega-cities in Asia and Africa can no longer be painted in any convincing way as somehow following a similar trajectory to others’ development. The long ago already Blade Runner-like cities of South America showed us how this dystopian future was actually a tale of the past. There is no developmental inevitability of an urban trajectory where every large conurbation arcs towards its own Blade Runner future.

If we little princes think about inequality more as a political concern, not a question of competing identities all requiring equal respect, then that Blade Runner scenario of a dominant elite with increasingly disproportionate power becomes less plausible. As DeVerteuil argues, it is not just our cities that have become more fragmented and fractious. It is also us, and ‘unlike the 1990s, the field of urban studies is currently far more imploded and fragmented, and less obviously driven by class analysis.’ (op. cit.) – why should that be? What happened to us to make us write and think so differently in the years after the 1990s?

We like to tell ourselves it was because of ‘out there’, that reality changed and we changed our theories with it. But what if it was what happened ‘in here’, in our lives, our minds, in the pages of our journals and in our classrooms and academic offices? We mostly grew up in the United Kingdom and United States, in places becoming more divided every year longer we lived.

There is something deeply conservative about academic culture, particularly in its radical iterations. Increasingly we (you and I, my colleague) were more likely to be of the me, me, me, generation and increasingly likely to come from those social groups that learnt to try to avoid imagining sleeping under the corrugated iron roof.

We are ever so emphatic but, in some ways, shallower too. We might complain that our students appear to wallow in the latest fad, but we too differ greatly from the generation above us in terms of what we experienced. We gentrified, and we (I and my generation) provided the stepping stone towards an entitled identitarian disposition to select a more arbitrary classification of injustice.

The activist Geography lecturer used to be the British old-Labour type, or the American hippy. Those have now almost entirely disappeared, to be replaced by the identitarians. DeVerteuil ends telling himself that he must resist the temptation to talk as they might have talked, but instead should wait for the emergent to emerge:

Davis (1990), like much of the self-professed (and much-maligned) LA School, was entranced by the spectacle of surreal inequalities, in turn inadvertently glorifying them, drawn in by the seductive dystopia of the Blade Runner scenario writ large. I must resist the temptation to frame the lopsided city in dystopic terms, given it remains emergent and uneven, such that the relationship between powerful and everyday fabrics continues to be ambiguous. (op. cit.)

Why must he resist? It is dystopic for the majority of people; including even for many of the little princes who most often today get to write theory but struggle to ever gain tenure. But I think DeVerteuil is right to describe the lopsided city, and by implication, the lopsided academy we work in as ephemeral. It will not hold up.

Opposition to the lopsided city must be more than destructive and angry. Like the successful progressive politics of old, it needs to also be constructive, community-building, and creative – to thrive. Find within the lop-sided city parts to love and cherish them. Love and kindness are words which culture warriors find hardest to counter, these are the holes in their lives.

Levelling the lop-sided city requires giving up on some of what has been hard won, but is not worth holding. The little identitarian princes have to begin to give up their hold on the cliff side, their beliefs that all inequalities are equal and, to ‘…this you have got to add the ugly fact that most middle-class Socialists, while theoretically pining for a class-less society, cling like glue to their miserable fragments of social prestige’.(2)

Something that is too lopsided will inevitably collapse, and with it all the miserable modern fragments of today’s newly re-spun gown of social prestige. The city of the future could, and very probably will, be far less lopsided than the ones many of us live in today. But only if we concentrate more on it, and less on ourselves.

Footnotes

1. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (1943) Le Petit Prince,

2. George Orwell (1937) The Road to Wigan Pier, Part Two, Chapter 11

References

Davis M (1990) City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles. New York: Verso.

DeVerteuil Geoffrey (2023) Urban inequality revisited: From the corrugated city to the lopsided city. Dialogues in Urban Research.

Danny Dorling is a professor in the School of Geography and the Environment at the University of Oxford (UK), and a Fellow of St Peter’s College. He is a patron of RoadPeace. Comprehensive Future, and Heeley City Farm. In his spare time, he makes sandcastles.

For a PDF of this commentary and a link to where it was first published click here