Dying Quietly: The New Suburbs

Mustn’t grumble. Mustn’t make a fuss. England’s suburbs are slowly dying, as years of austerity slowly changes the landscape. Since 2014, life expectancy has been falling across most of England, especially in the suburbs. The elderly are now dying faster than before. And it is in the suburbs, far away from your children (if you had children), that you now much more often live and die alone.

The mantra that there is no such thing as society, just families and their children, rings both true and hollow in the suburbs.

The suburbs are changing more quickly today than they have changed in decades. The centres of cities are increasingly reserved for the young, the successful and those who can afford to avoid long commutes. Out of town villages are where the very affluent go when they age—the idyllic cottage in the country.

Rising economic inequality

In the great suburban new hope of the era from 1930 to 1970, the suburbs were supposed to be where life’s winners went. Suburban schools were ‘good’, suburban jobs were plentiful and well paid. Suburban doctors were not over‐worked; hospitals were accessible. But the money began to run out in the 1970s.

England accommodated its loss of empire by accepting rising economic inequality. After the 1970s the country as a whole became poorer in comparison with the rest of the developed world and with most of Europe, but in the 1980s, 1990s and noughties those at the top took a greater and greater share of the pie each year. As they did so they took more and more from the poor and from suburban middle England, from the places where the majority lived, the places that saw progress stall.

Today there are far fewer winners, so those fewer winners win much more. The semi‐detached three‐bedroom suburban house is now the place you end up in if you have not failed but also have not succeeded. The bills remain high, the council tax rises, the repairs have to be done. This is beginning to swing suburbs in the south of England towards Labour.

Suburban Conservative‐voting England, where the fewest immigrants arrive, is where UKIP did best in various votes before 2017. We try to pretend it is the poor council estates, the east coast and ‘the north’ where this dissatisfaction was greatest; but that is not where the sense of loss was strongest.

In 2007 the best‐off one per cent of people in the UK took 15.4 per cent of all income. The suburbs suffer the most from such inequality. In other European countries, where the one per cent take less, the poor do much better—but it is the suburbs that most benefit from greater economic equality. Compared with Scandinavian norms the best‐rewarded one per cent of people in the UK take enough extra to fund a second national health service.

The suffering of the suburbs

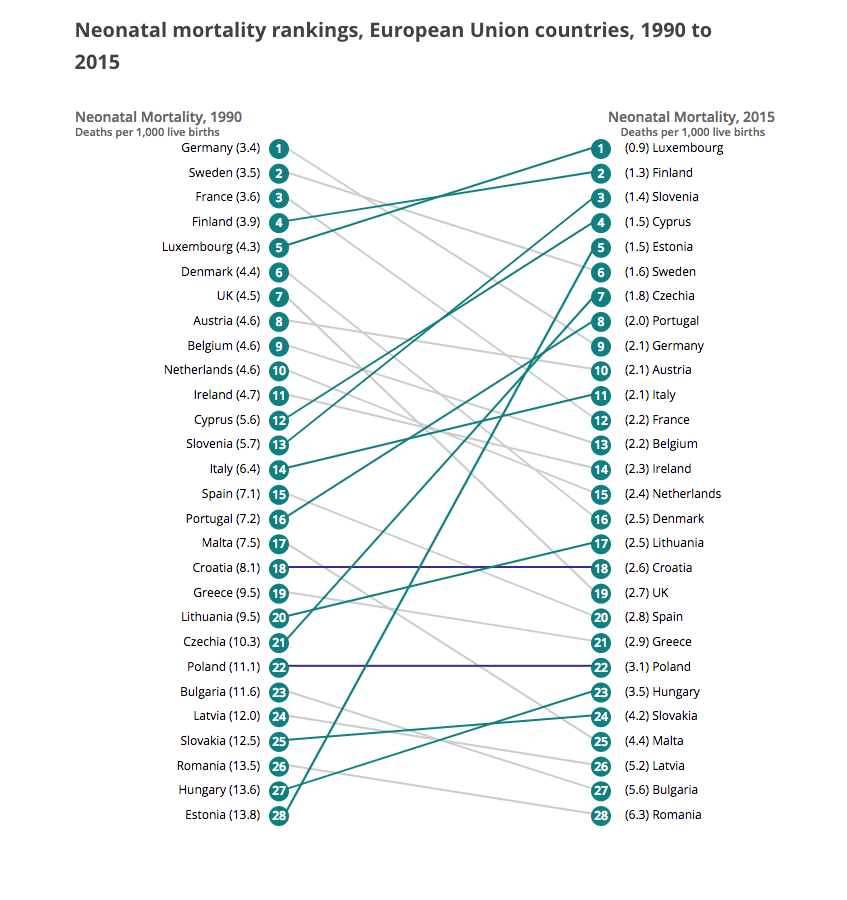

Between the censuses of 2001 and 2011 the number of people who had to resort to private renting in the UK doubled. The increases were greatest in the south‐east and especially within London. This was portrayed as a ‘buy‐to‐let revolution’ but it was led by landlords who owned multiple properties, not by ‘small investors’. And all the time living standards in the UK, especially in England, were falling in relation to those in the rest of Europe. This is illustrated most dramatically by the changed ranking in neonatal (first twenty‐eight days) mortality rates from 1990 to 2015 (see Figure 2).

Neonatal mortality rankings, European Union countries, 1990 to 2015

Figure 2: Neonatal mortality rates, EU countries, 1990–2015

The decline in living standards was felt most acutely in the suburbs. They are where more and more of the food banks are placed and the gas bills are not paid on time. From slowing improvements in infant mortality, through to declining school budgets, low wage work for the majority, the introduction of crippling student loans leading to precious jobs, and then paying the highest rents in Europe, the problems of the English were no longer concentrated in ‘those inner cities’.

Poverty rose faster in outer London than inner London. It is in southern England’s suburbs where poverty rose the most between the 2001 and 2011 censuses. So gradual and hidden was the rise that without a census it could not be seen.

When, in 2016 and early 2017 young adults in Britain looked at what was increasingly on offer, they began to balk at the unfairness of it all. Large numbers did not vote in the general election of 2015; Labour did not offer them much of an alternative then. Almost as many young adults did not vote in the referendum of 2016, for either side. Again, what was there for them to vote for? But come June 2017, their votes were against the landlords, against student fees, and against the decay of the suburbs that was increasingly looking like their fate.

….

The architecture of wealth extraction

Joe Brewer writes: “The architecture of wealth extraction is a cancer on this planet. It continually corrupts our governments, poisons the natural environment, and pits us against each other in a ‘race to the bottom’ that has only one logical outcome – the wholesale destruction of life‐giving capacities for the only home planet we’ll ever have.”

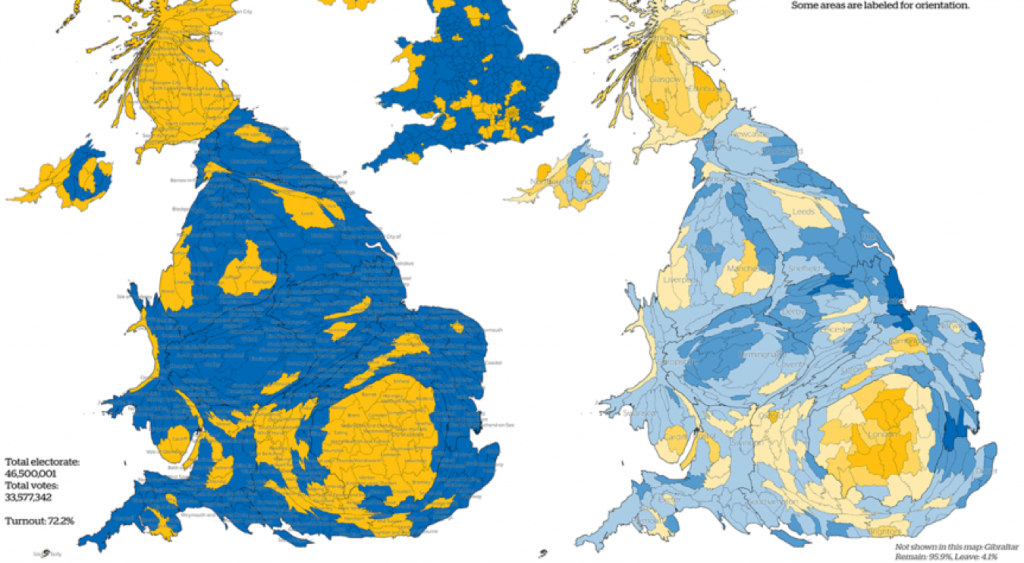

It was the suburbs that voted Brexit. Just look at the map and forget your preconceived prejudices. The map shows the pattern. If you want a modern day definition of suburb in England it could be: that part of the end of your town or city where the majority of people quietly, desperately and angrily voted to leave the EU as they felt on the edge.

Areas are shaded by whether a majority who voted voted to Leave or Remain and also by the proportions voting in these ways

Figure 3: The human geography of the EU referenced vote, 2016

The English and American suburbs are both quietly dying. They are no longer places of success, but have become places of social and political retreat (where people hark after ‘being great again’). The US vote for Trump was highest in those suburbs in which the health of Americans was declining most quickly.

What matters for this analysis is that the break occurred between 2015 and 2017. Before then the situation simply appeared to be worsening continuously. For example, mortality rates in the UK remained high in 2016 and among the elderly peaked again in early 2017. What was most shocking was how little attention this received. It is as if we now expect it. But as the June 2017 UK election result showed, people had begun to notice and to react. As I write (in May 2018) support for Corbyn’s Labour party still lies at 38 per cent of all voters—as it did in June 2017.

The revolt of the suburbs: Brexit

The old party of the suburbs were the Conservatives. Their suburban grip remains strong but was then weakened by UKIP. Today most of the UKIP vote, built from suburban discontent, has returned to the Tories. Today, they now offer Brexit as suburban salvation. Like Trump, they will now build a wall to stop more migrants, but it will be an invisible electronic wall of visa restrictions and entitlements reduced. This, they promise, will ‘make Britain great again’.

We sold dear to the empire and brought cheap from it. Those days are gone. Failure to replace the empire with an alternative, while allowing the one per cent to take more and more, is what has been killing suburbia.

In the US and the UK, the architecture of wealth creation has been allowed to take a particular form which is now harming the wellbeing of the majority, especially the young. This is why suburbia is now suffering.

All across England, suburbs are changing from places of aspiration to neighbourhoods where many can be frightened into voting to ‘take back control’. But the suburbs need to be recaptured by the young. If the next generation is to settle down and have children in the suburbs then they need to win those suburbs back—politically—from the landlord and the ideology of let the Devil take the hindmost.

…

This blog is adapted from a longer piece in the Political Quarterly journal:

DANNY DORLING

Danny Dorling is a British social geographer and is the Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography of the School of Geography and the Environment of the University of Oxford.

click here to read more, for the link to the journal website and for a PDF of this article.