Public Inquiry into rising mortality in England announced

In June 2018 the UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) released data for England that revealed mortality rates to be rising across the country. This rise in mortality rates had occurred even after having taken out the likely impact of population ageing. In other words, more people were dying and that was not because of a greater proportion of people becoming older.

On August 1st 2018 the BBC reported this news under the headline “Why did more people die in the depths of last winter?” and also announced that the Department of Health were still to announce the terms of reference of an official inquiry into the deaths although it is ‘understood they will cover areas like excess winter deaths and deprivation.’ This was not very reassuring given the much longer list of possible causes that had been published almost two months earlier in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine.

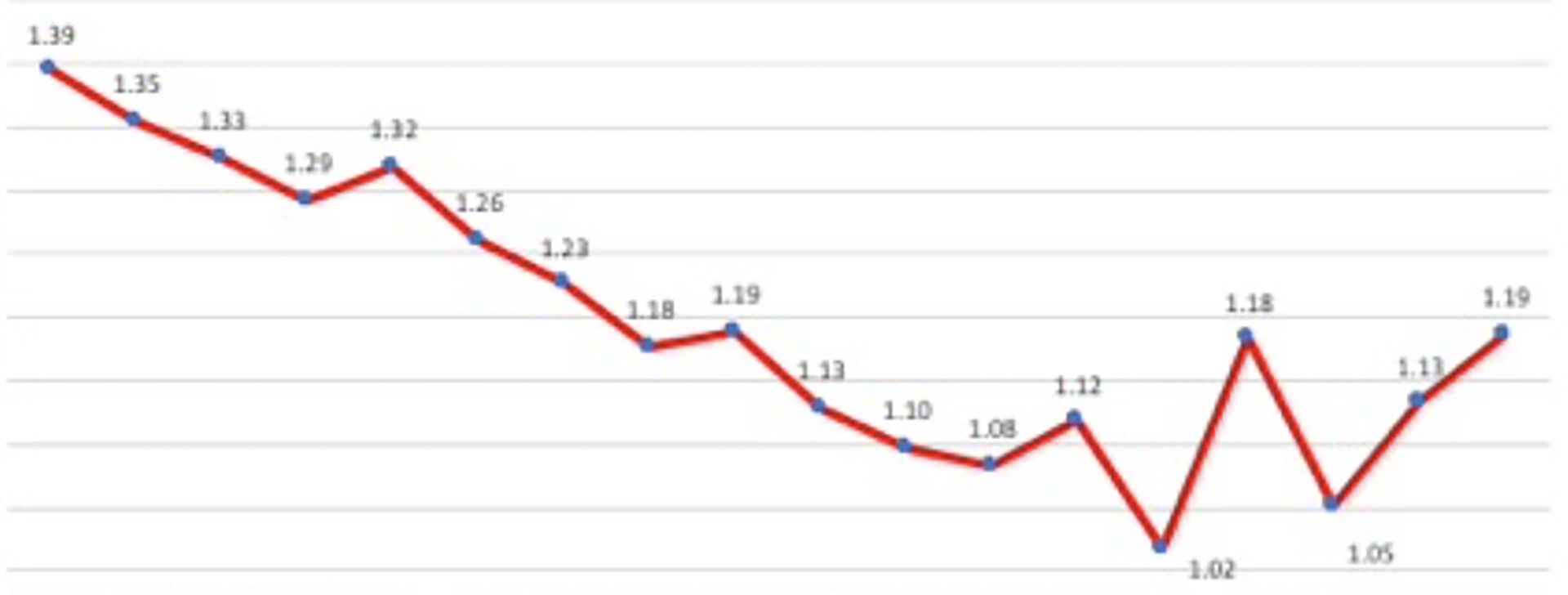

The rise marked the end of a longer period of improvement that had lasted from long before the Second World War through to around 2012. As the figure taken from the ONS report below shows, there had been the occasional very small rise before, as occurred in 2005 and 2009 .

Note: shows proportion of people dying each year in England at quarter 1 rates

Source of graph: ONS

According to the Met Office the winter of Quarter 1 2009 was the coldest since 1995/6 in England and Wales. Partly as a result of the unusual cold there was a slight rise in age-sex standardized mortality between Q1 2008 and Q1 2009. Similarly, in Q1 2005, there was a great deal of snow. More recent winters have been much warmer. There has been no unusually cold winter since at least 2011. The cold does not account for what has happened recently. It did not become very cold until late February in 2018.

The recent rises in mortality rates were also not due to influenza. As the ONS commented in June 2018: ‘influenza activity remained at medium levels throughout the whole of January and February 2018.’ No influenza epidemics have been recorded in any recent year; the rapid rise in mortality in England is not due to influenza.

ONS published analysis in June 2018 that concluded that the change in the mortality trend could be shown to have occurred between 2011 and 2012 for the age groups that were most effected. So we now know when whatever has happened began to happen.

Data is available on the number of deaths that occurred in each area of Britain in Quarter 1 2018 and Quarter 1 2016. This is the period shown in the graph above in which the greatest rise in age-sex adjusted mortality rates occurred most recently. There will also have been changes to the age structure of the population in these areas, but these are likely to be slight. The table below shows the 22 local authority districts in which at least 100 additional people died in the same quarter of 2018 as compared to 2016, and in which there was also at least a 25% rise in mortality rates.

Table 1: The areas of England which experienced the greatest relative increases in mortality, Q1 2016 to Q1 2018 Increase <Deaths in three months> in deaths Q1 2018 Q1 2016 %rise District 129 411 282 46% South Staffordshire 125 419 294 43% West Lancashire 123 418 295 42% Preston 143 510 367 39% Huntingdonshire 182 655 473 38% Hillingdon 111 402 291 38% North Kesteven 134 508 374 36% Suffolk Coastal 117 454 337 35% Stafford 100 390 290 34% Gedling 110 431 321 34% Wycombe 171 687 516 33% Central Bedfordshire 205 883 678 30% Stoke-on-Trent 106 460 354 30% Eastbourne 126 564 438 29% South Tyneside 109 489 380 29% Waveney 123 557 434 28% Wealden 115 546 431 27% Harrogate 135 642 507 27% Bexley 100 476 376 27% Chichester 182 873 691 26% Wolverhampton 116 558 442 26% Northampton 104 512 408 25% Redcar and Cleveland

Source: ONS

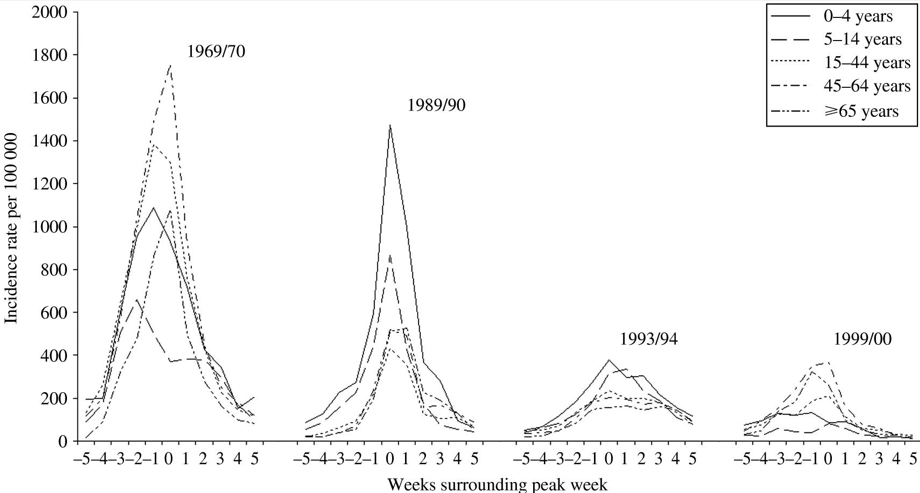

The diagram below shows what the pattern of an influenza epidemic looks like in terms of severity and duration based on the epidemics that did take place in England in the winters of 1969/70, 1989/90, 1993/94 and 1999/2000. If we were to suffer an influenza epidemic this is the most likely pattern in terms of severity rising rapidly over the course of less than five weeks and then falling equally rapidly again. An influenza epidemic (in winter 2018/2019 say) on top of what has already been happening would be devastating.

The weekly incidence of Influenza-like illness (ILI) by age for a selection of the more severe epidemics over the last 40 years. Age-specific rates are for the weeks surrounding the peak week of all-age incidence (week 0)

Typical length of time and severity of influenza epidemics in England, 1960-2000

Source: Fleming, D.M. and Elliot, A.J. (2008) ‘Lessons from 40 years’ surveillance of influenza in England and Wales. Epidemiology and Infection, 136, 866-875.

By larger geographic area the greatest absolute and relative rise has been in the county of Lancashire. The table below shows in which counties and regions of England and Wales the rise has been the greatest where at least an additional 100 deaths occurred.

It is worth noting that the rise tends to be lower in areas with fewer older people, such as Inner London and some of the Northern Metropolitan Counties. The overall rise was 16% in England, an additional 20,907 deaths in the first three months of 2018 as compared to the first three months of 2016.

Table 2: The Regions England and Wales, sorted by increases in mortality Q1 2016 to Q1 2018 Increase <Deaths in three months> in deaths Q1 2018 Q1 2016 %rise Region/County 726 4030 33,04 22% Lancashire (County) 2,259 13,992 11,733 19% EAST MIDLANDS 2,738 17,399 14,661 19% WEST MIDLANDS 2,788 17,825 15,037 19% EAST 3,519 25,105 21,586 16% SOUTH EAST 20,907 153,635 132,728 16% ENGLAND 1,395 10,502 9,107 15% WALES 2,839 21,987 19,148 15% NORTH WEST 1,100 8,662 7,562 15% NORTH EAST 2,012 16,066 14,054 14% YORKSHIRE AND THE HUMBER 2,113 17,651 15,538 14% SOUTH WEST 732 6,289 5,557 13% West Yorkshire (Met County) 859 7,411 6,552 13% Greater Manchester (Met County) 483 4,571 4,088 12% Merseyside (Met County) 1,539 14,948 13,409 11% LONDON 392 4,637 4,245 9% Inner London Source: ONS

The table above is from the same source and shows mortality numbers rose the most in the Midlands Regions (just below Lancashire’s slightly higher relative rise). Incidentally, rises tended to be higher in areas that mostly strongly voted Leave in the 2016 referendum. Mortality rose by national average rates in the North West; but much more in more rural and older (aged) Lancashire than in urban Merseyside. The rates rose the least in London, especially inner London. Inner London has the highest proportion of migrants from overseas.

The inquiry will have its’ work cut out explaining why middle Britain was so badly hit and why almost all of England also suffered so much. The final table below shows the few areas of England which experienced a fall in mortality between these two years. A fall is what would normally be expected everywhere, and a larger fall than the very small reductions in some of the areas listed below. Finally, note that the City of London, Oxford, Kensington and Chelsea, and a tiny number of other southern boroughs and towns appeared to be the only areas of England to be almost entirely unaffected by what has just occurred and is presumably still occurring throughout 2018 and into 2019.

Table 3: The few areas of England with a fall in mortality Q1 2016 to Q1 2018 Increase Deaths in three months in deaths Q1 2018 Q1 2016 % rise District -1 192 193 -1% South Bucks -3 496 499 -1% Milton Keynes -2 180 182 -1% Tamworth -4 352 356 -1% Fareham -14 326 340 -4% Haringey -24 444 468 -5% Colchester -28 446 474 -6% Bath and North East Somerset -20 298 318 -6% Hackney -11 160 171 -6% Epsom and Ewell -18 252 270 -7% Oxford -1 11 12 -8% City of London -27 209 236 -11% Kensington and Chelsea -2 6 8 -25% Isles of Scilly Source: ONS

Read a pdf of original article here.

And a link to the July/August issue of Public Sector Focus it was published can be found here.