Making Britain worse and better in 2025

Bingzhi Zhu was a foreign student from China. Her student visa did not extend until the May of 2021; but she only realised this a day before it was due to expire. So, she paid the processing fees to apply to have her visa extended. However, her application for an extension was not completed because her university could not add the information only it could supply – confirming the postponement of her graduation. The reason it could not do that in time was that the application was made on a public holiday.

The Danish authorities arrived at Bingzhi’s student room without warning and before the public holidays were over. They arrested her in her student room and took her to Vestre Fængsel prison before transferring her again: According to reports: ‘She spent several days at the psychiatric departments at Amager and Bispebjerg hospitals and then was taken to Ellebæk, a migrant detainment facility. Only last year, the latter has been accused by the Council of Europe’s Committee for the Prevention of Torture for the way they treated those detained.’

Bingzhi described her experience as ‘hell’ and some of the places where she was held as ‘training grounds for racists’. It was later revealed that the University of Copenhagen had tried to get her out of the facility but failed. She was deported rather than be allowed to attend her graduation. Her last memories of Denmark were guards at the Ellebæk calling every Chinese person ‘China’.

The story of Bingzhi Zhu became high profile in Denmark. In the Danish parliament the immigration minister was asked: ‘[Do you consider it] fair that a young Chinese student who was only in Denmark to study can end up in Ellebæk as a result of an expired visa, a place that has been strongly criticised by the Council of Europe’s torture committee for prison-like conditions?’. The minister did not answer.

Four years later the British government announced that it had been watching Denmark closely and wished to emulate its approach. These were conditions so strict that any failure, such as receiving a speeding ticket for driving too fast, can (according to journalist Miranda Bryant) lead to someone seeking legal settlement having their eligibility date pushed ‘many years into the future.’ It is a system designed to make an entire country appear unwelcoming – a place to be avoided.

In late 2025 Bryant interviewed Eva Singer, the director of asylum and refugee rights at the Danish Refugee Council, who said: ‘The politicians say they follow the popular mood, but maybe the popular mood is coming from what the politicians are saying, which is not based on fact.’ In other words, in Denmark it has been: ‘politicians, not the public, driving anti-immigrant sentiment’.

Bryant suggested that it will be the 2026 general election in Denmark which will tell us: ‘whether or not the [Danish] Social Democrats’ approach is still popular with voters. Immigration is likely to be one of many hot-button issues. Others include Donald Trump’s threats to Greenland, a former Danish colony that remains part of the Danish Commonwealth….’ She also quoted Danish journalist Rune Lykkeberg who suggested that the Social Democrats’ handling of immigration followed a ‘Danish playbook’ which has now been used in the same way in Denmark for more than half a century, whose usefulness might well be coming to an end: ‘The politics of it is part of what you could call the Danish model: you don’t try to burn the so-called populists, you try to steal their fire. You keep the so-called extremists from the centre of power and thus defend the old political order.’

Contrast Denmark with the Netherlands, another country that the British government might have looked to instead. Just a few weeks before the British government announced it would try to emulate Danish immigration policy there was a ‘snap’ general election in the Netherlands. That election was caused by a far-right anti-immigration party leaving the governing coalition. In the event, the far-right led party secured only 16.66% of the vote, slightly behind the Social Democrats who surprised observers by securing a fraction more: 16.94%. Their triumphant leader, 38-year-old Rob Jetten, was slated as being most likely to become prime minister, and analysts projected an alliance of 88 progressive MPs from many parties forming a government, but one which would not be very stable as it would only have a majority of 9 seats.

As Le Monde reported in late November 2025, regarding Jetten, he ‘…will either have to bring together the liberal right and the socialist and environmentalist left, thus overcoming deep divisions, or turn to smaller parties that risk weakening his future coalition. Currently, 15 parties are being represented in a House of Representatives more fragmented than ever before, and Jetten’s first challenge will be to quickly deliver on one of his campaign promises: to restore stability to a country that has been through nine different governments since 2002 and three elections in just five years.’ All of Europe watches the rest of Europe and holds its breath with hope and trepidation – except Britain which has chosen a half-century-long-standing (and slowly failing) policy from Denmark to emulate.

Why is Britain in this quandary? Speaking back in June 2025, political commentor John Curtice put it thus: ‘People who say they’re struggling on their income are less likely to be trusting politicians. Those who think the health service is not doing very well are less likely to be trusting politicians and governments. So these things are related. The risks that face this government and the opposition collectively were very, very clearly there in the election.’

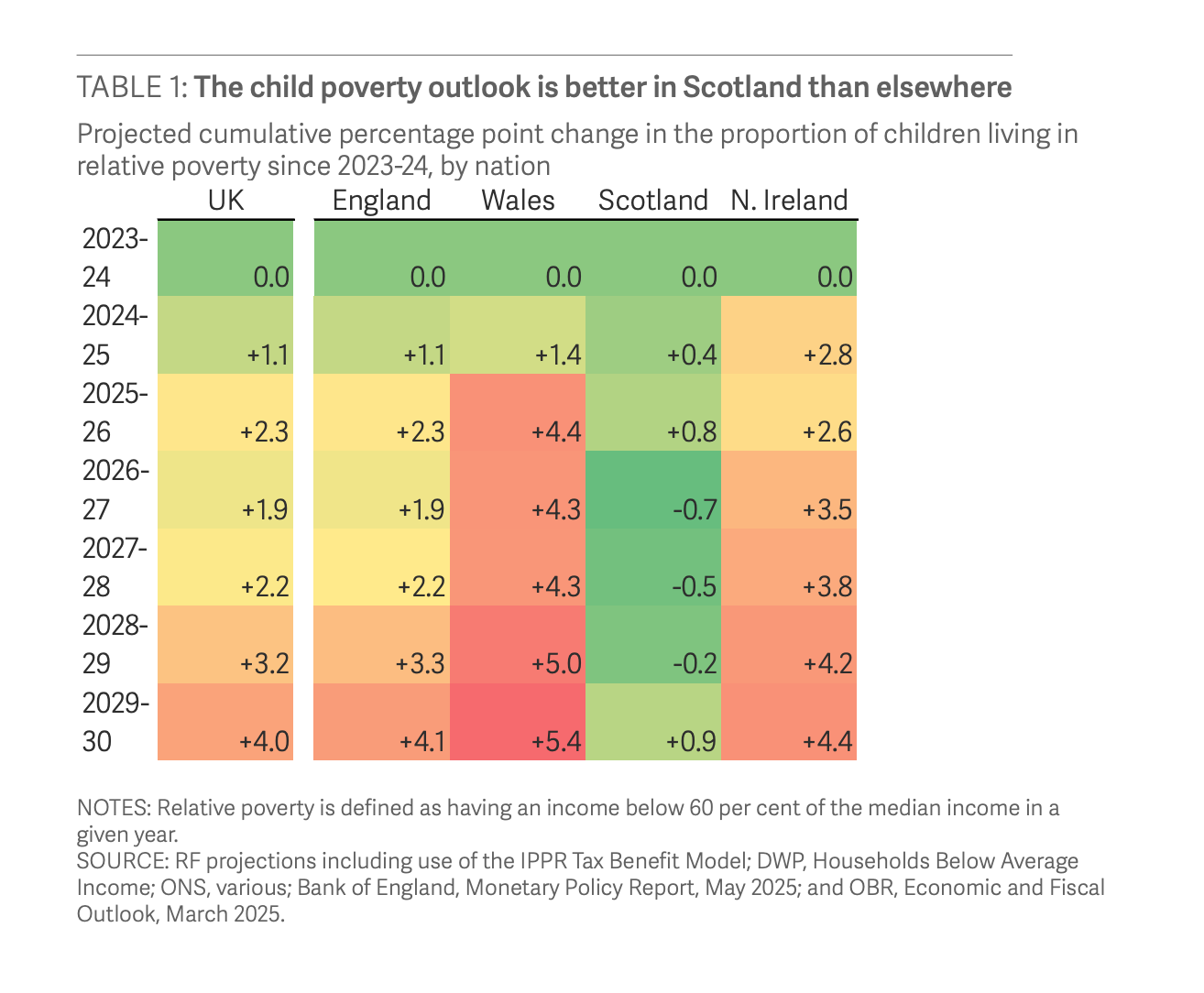

In that same summer month of June, the Resolution Foundation published forecasts for what the future in the UK held for children. Their report contained a table that showed the differences across the United Kingdom. This key table, hidden at the very end of the report, is shown here as Table 1 of the Appendix to the IFS report ‘The Living Standards Outlook 2025’ – published on 26 June 2025.

Child Poverty Outlook is better in Scotland than elsewhere

Table 1 (above) showed that, other than in Scotland, child poverty in the UK was projected to rise by between 4.1% and 5.4% by 2029-2030. However, this forecast held only until 26 November 2026, the day of the autumn budget. Almost certainly in response to figures such as those present in Table 1, the Labour government finally decided on that day to enact its promise to removing the two-child benefit cap that existed in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In Scotland the Scottish government made special payments for families receiving any universal credit. This policy alone in Scotland resulted in the forecast for Scotland being an improvement, apart from in the year 2029-20. However, now that rise should become a fall, everywhere, and probably a far faster fall in Scotland still. The BBC headline that day read: “‘No austerity or reckless borrowing” Reeves says, as she unveils tax rises and ends two-child benefit cap’.

So, on the one hand the Labour government had a policy aimed at making the UK appear like a worse place to come to – seeking to deter migrants. But, on the other hand, it was also finally trying to reduce child poverty and make the UK a better place to grow up in. It is hard to see how both policies can operate successfully at once; or why deterring migrants would help make the UK a better place to live in. Migrants tend to be associated with greater economic growth of the beneficial kind, and more jobs – because they more often work, or create work, as in the case of Bingzhi Zhu (whose presence in Denmark created work at the University of Copenhagen).

Interestingly, the UK budget also set an international student fee at a flat rate of £925 per student, though not to take effect until the 2028-29 academic year. It had been rumoured that the fee would have been far greater than this for some students. The reason it was not, was very likely the realisation that a higher international student fee would reduce overseas student recruitment, and cost the UK jobs.

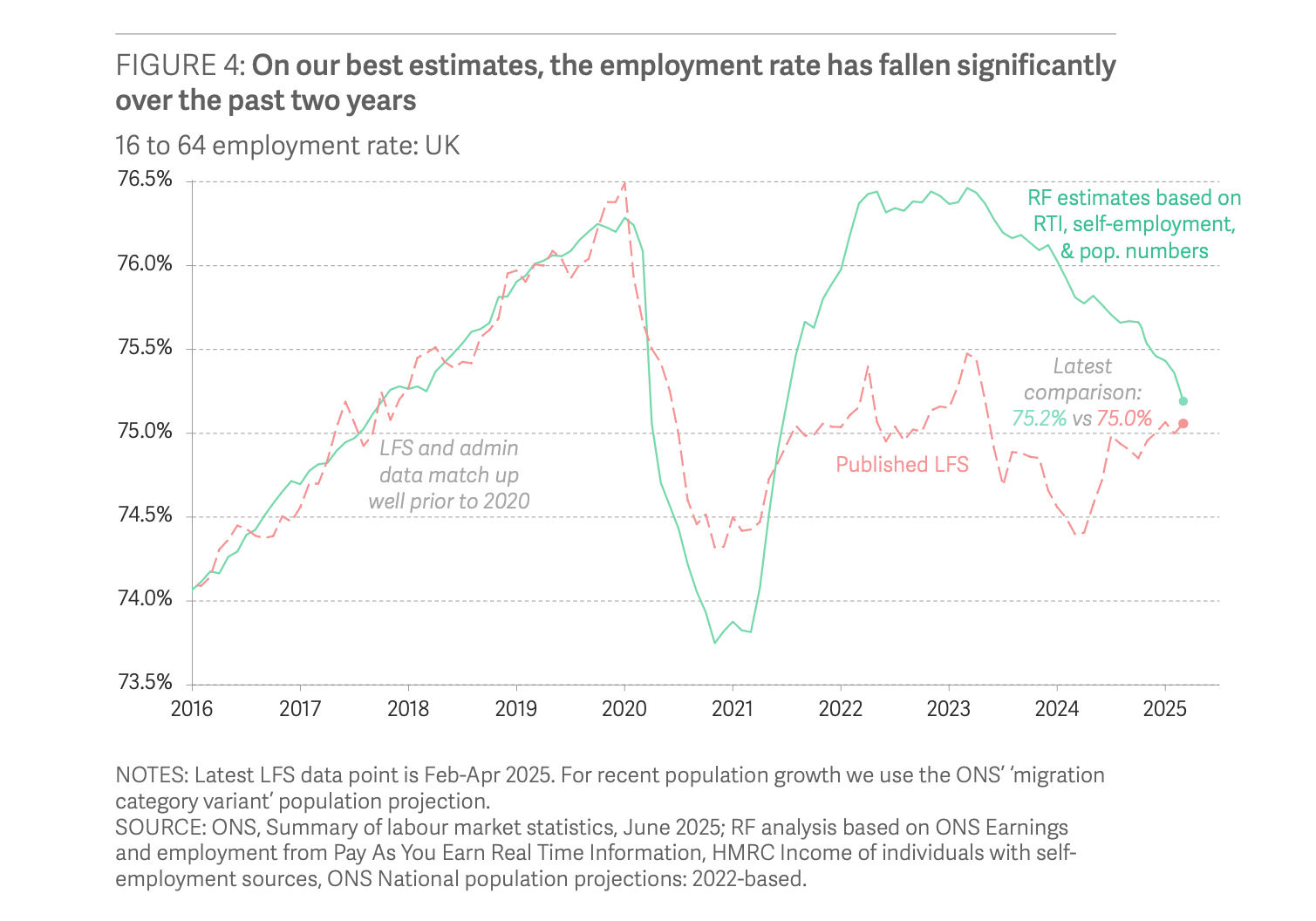

There is one last chart in that Living Standards Outlook 2025 report worth closing on. Figure 4, also reproduced here (below), shows that employment rates are currently falling in the UK. The fall in the last two years has been as great as that in the first few months of the pandemic. It may well be the case that in future the UK government will have to worry about jobs more than it does now. Reducing migration would only increase unemployment.

Employment rates the the UK have fallen significantly over the past two years

References

https://schengenvisainfo.com/news/denmark-imprisons-chinese-student-for-overstaying-visa-after-she-failed-to-graduate-on-time-due-to-covid-19/

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/nov/14/the-uk-wants-to-emulate-denmarks-hardline-asylum-model-but-what-does-it-actually-look-like

https://www.dutchnews.nl/2025/10/the-netherlands-shifts-to-the-centre-rob-jetten-set-to-be-pm/

https://www.lemonde.fr/en/opinion/article/2025/11/15/netherlands-sees-uncertain-victory-against-populism_6747472_23.html

https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2025/jun/25/class-age-education-dividing-lines-uk-politics-electoral-reform

For the original first publication of this article and a PDF click here.