Who should be vaccinated before others?

In late January 2021, when I wrote these words, a debate was raging as to whether people working in particular occupations should receive COVID-19 vaccines before people working in other jobs, and possibly even before some much older people. That debate may still be raging when this piece is published.

On the 25th of January 2021 the Office for National Statistics produced a report entitled ‘Coronavirus (COVID-19) related deaths by occupation, England and Wales: deaths registered between 9 March and 28 December 2020’. The report began by explaining that COVID-19 had contributed to 7,961 deaths of people aged 20-64 during this whole period, an average of 27 deaths a day.

COVID-19 had contributed to the deaths of almost ten times as many people over the age of 64 in that same ten month period. COVID-19 is a disease that is fatal mainly in older people. Many people, most especially older people, who recover also suffer long term illness from it. On that same 25th January day, one sufferer from the disease, Paul Garner, (Professor at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and Director of the Centre for Evidence Synthesis in Global Health and Co-ordinating Editor of the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group) wrote in the British Medical Journal: ‘I write this to my fellow COVID-19 long haulers whose tissues have healed. I have recovered. I did this by listening to people that have recovered from CFS/ME, not people that are still unwell; and by understanding that our unconscious normal thoughts and feelings influence the symptoms we experience.’ He was explaining that even those, like him, who had been badly affected but were not very old often recover. He was doing this because the fear of the disease was so great at this time.

COVID-19 is a terrible disease, but it affects some people much more badly than others. Just as ten times as many people had died of the disease aged 65 and over, as compared to those of working age in 2020, so dramatically fewer aged under 20 had died partly (or mainly) due to COVID-19 in the same ten months being compared – just some 21 people in England and Wales, mostly young children. In contrast, almost 4000 children had died of other causes in 2020.

Some 99.5% of the people aged under 20 who died in England and Wales in 2020 did not have COVID-19. Some 90.5% of all the people aged 20-64 who died in 2020 did not die due to COVID-19. One occupation where the risk of mortality was almost identical to the national average was teaching. Among people working as teaching and educational professionals, 89% of the deaths that occurred in 2020 had nothing to do with COVID-19. However, many people of working age certainly feared this disease above anything else that year. Only one third of those aged 20-64 who did die of COVID-19 were aged 20-54; and only one third were women.

By occupation it was men who worked in the very lowest paid occupations, classified as elementary jobs, such as cleaning, who had the highest rate of deaths (699 deaths) and next those men working in caring, leisure and other service occupations. Women in those occupations also had some of the highest rates for women, but faced roughly half the risk men faced.

We do not yet know why men of any given age and job were twice as likely to die as women. In some occupations where there are many more women working than men, the mortality rate is higher for men, but more women die overall. For example, as ONS succinctly put it: “Men (79.0 deaths per 100,000 males; 150 deaths) and women (35.9 deaths per 100,000 females; 319 deaths) who worked in social care occupations had statistically significantly higher rates of death involving COVID-19 when compared with rates of death involving COVID-19 in the population among those of the same age and sex.” And we do know that “Rates of death involving COVID-19 in men and women who worked as teaching and educational professionals, such as secondary school teachers, were not statistically significantly raised when compared with the rates seen in the population among those of the same age and sex.” That last finding provoked much anger, but not a great deal of reflection.

ONS report on mortality by occupation for men

A website, The SKWAWKBOX, claimed that the ONS figures were misleading because they did not include people whose occupation was teaching but were aged over 64. Perhaps their reporter did not know that death certificates record last known occupation, but don’t actually record whether someone was working recently or was long since retired when they died? That website went on to explain that: “…the National Education Union (NEU) revealed that Department for Education data showed that rates of infection among education staff is between twice as high and seven times as high as in the wider population.” Given all this it was hardly surprising that many teachers were in such fear. However the ONS figures are the only ones that are comparable with other occupations and which are actually about people at work (not adding in also those who are retired) – and they very clearly explain that working teachers had average chances.

ONS report on mortality by occupation for women

It is not hard to see why the ONS statistics were so contested. For someone who was a teacher, the fact that they were a teacher did not significantly increase their chance of dying of this disease compared to anyone else (although most did not feel this). Logically, if they were near retirement age it is that risk they should have been worrying about far more; twice as much if they were male. After that, they should probably have worried about whether they lived in a big city, in an overcrowded household and/or in a poorer area (where rates of the disease have tended to be much higher). In hindsight, given the statistics released in 2021, they should have worried if they already had (or were at risk of developing) diseases affecting the lungs, heart, kidney, liver, brain, nervous or immune systems, or had diabetes or were very obese; and actually worry more about all the other risks of those conditions and less about the increased risk if they caught COVID-19.

The geographical and occupation patterns largely explain why people of Black or South Asian ethnicity were more likely to be at risk of the disease. For people of working age, dying of COVID-19 in 2020, once age, sex and geography had been accounted for – was mainly a question of social class – and this was as true among the public sector workforce as among the private sector. The more posh your job, the less likely you were to catch the disease, or possibly fall ill from the disease if you did catch it, or die of the disease if you did fall ill. The two graphs below illustrate this very clearly. They show how, all else being equal, that the man who cleans an office was four times as likely to die of this disease in 2020 than the professional who decided when the office was cleaned. And the woman who worked on a production line in 2020 was more than four times as likely to die from the disease than a woman working in an associate professional or technical occupation (such as teaching).

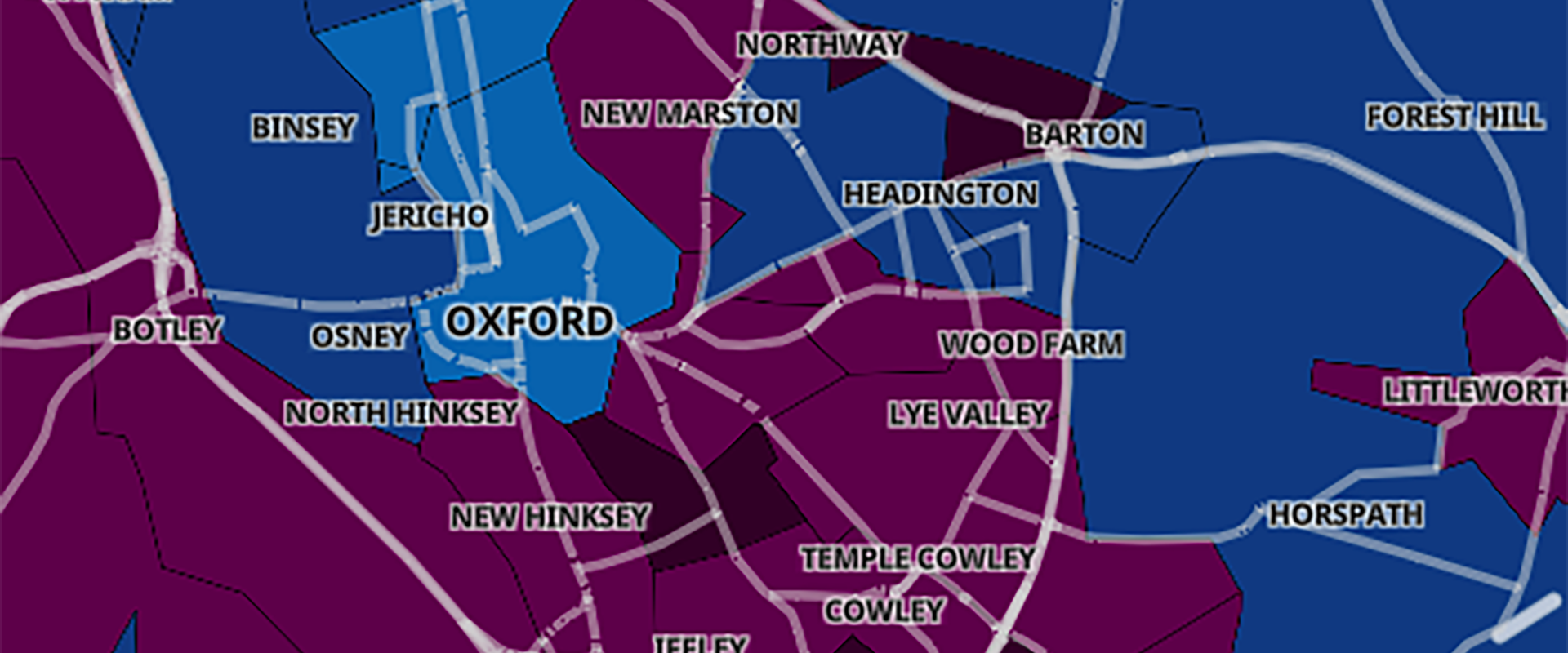

If COVID-19 is still rampant when you read this, take a look at the map of your area on the government’s dashboard. I have included an example for Oxford here. Had there been space I could have included a map of deprivation in Oxford, but I really don’t need to as this map of the disease is almost identical.

Finally, who should be vaccinated before others, after the older priority groups? Clearly the occupations that are poorly paid are most at risk – but they have few in the public eye to argue their case, or political parties that are bothered about their votes, as opposed to the votes of those much less likely to die, and always more likely to live for longer.

Figure 3: rates of infection from COVID-19 in and around Oxford in late January 2021.

Source: Government dashboard.

Currently the plan is that everyone over 18 should be offered the vaccine and hopefully most will accept it. The quicker that is achieved, the better. But we cannot condone the 48-year-old doctor in Texas who stole nine doses of COVID-19 vaccine to give to his friends and family first. In the UK the current government has been much criticised for getting its priorities wrong, for being keener to benefit its friends and associates than openness, transparency and the greater good. It will be interesting to see what decisions they make after the oldest and most at risk groups have all been vaccinated.

The poorest in our society do not grieve less when a close friend dies. If they do not die, but suffer from long-term disability due to COVID-19, they cannot retire on medical grounds and get a pension, but are at the mercy of our mean social security system.

We are all fearful of the pandemic, but need to consider the whole of society, not just ourselves. It is very unlikely that COVID-19 will be eliminated in the foreseeable future or even very long term future. Once all adults have been offered an initial vaccination, we will probably vaccinate everyone on leaving school, and older age-groups periodically. The risks are so low for school children that we may never vaccinate them (and no current vaccine is licensed for use with children).

For a PDF of this article and a link to the original source click here.