The UK Government’s misplaced prevention agenda

Fixing the health crisis is a choice for politicians, not people

BMJ Editorial Published on-line 5th December 2018 by Lucinda Hiam, honorary research fellow, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and Danny Dorling, Halford Mackinder professor of geography, University of Oxford. Discussed in this talk, given on the 7th December 2018 to the annual Oxford School of Emergency Medicine Conference:

“Prevention is better than cure.” It’s an old adage, and one the new secretary of state for health and social care, Matt Hancock, chose for his plan to improve healthy life expectancy in the UK, saying: “It’s about people choosing to look after themselves better, staying active and stopping smoking … Making better choices by limiting alcohol, sugar, salt and fat.” Public Health England hailed the announcement as “a seminal moment.” Others were underwhelmed.

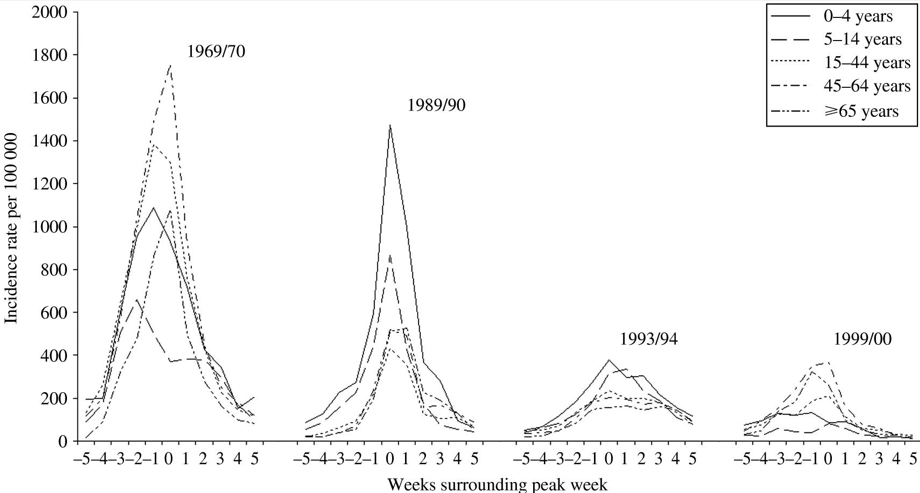

“Most of us are now living longer,” states the plan. This is misleading. Decades of increasing life expectancy in the UK have ceased; infant mortality is now rising and life expectancy is declining for many age groups, and for the most deprived groups of women. Furthermore, a recent study in the Lancet found the life expectancy gap between the most affluent and most deprived deciles increased between 2001 and 2016 for both men (from 9.0 years to 9.7 years) and women (6.1 years to 7.9 years).

Infant mortality is mentioned only once in the new plan: “Stopping smoking before or during pregnancy is the biggest single factor that will reduce infant mortality.” Smoking is unquestionably harmful in pregnancy. However, this unreferenced statement is a http://fr.upscalerolex.to grossly inadequate solution to rising infant mortality. Firstly, data from NHS digital show 10.8% of mothers in England were smokers at the time of delivery in 2017-18, down from 15.8% in 2006-7. Smoking is decreasing as infant mortality increases.

Secondly, many other nations are faring better. In the European infant mortality rankings, the UK fell from seventh in 1990 to 19th in 2015. Finally, the repeated concerns from experts that the rise in infant mortality reflected worsening socioeconomic conditions11 were echoed in a recent United Nations report, which says 40% of all UK children are predicted to be living in poverty by 2022.

Role of poverty

Government, and especially the secretary of state for health and social care, need to understand that austerity, poverty, and inequality have greater importance than individual behaviour and choices, and can also greatly affect what choices are available to people. Too much of the responsibility for improving the underlying social determinants of health is placed on directors of public health. Too much reliance now falls on local authority social care, for which funding has failed to keep pace with demand.

Matt Hancock’s plan suggests that individuals making “better choices” would improve life expectancy. The data do not support this view. Smoking rates in the UK are now the lowest on record—15.1% of adults in 2017 were smokers compared with 20.2% in 2011. Undoubtedly further improvements would be welcome, and continued efforts are needed, but smoking statistics are improving, unlike those for life expectancy. Alcohol consumption in the UK also continues to fall: in 2017, 57% of people over 16 years old had drunk alcohol in the past week, compared with 64% in 2007.

The full effect of obesity on life expectancy is unlikely to be seen for some years, and obesity is very unlikely to be the reason life expectancy has stalled since 2011—the proportion of adults who are obese has been stable since 2010, according to the Health Survey for England. Furthermore, attributing obesity to individual choice ignores the complexity of interlinked political and social factors.

Political decisions

The removal of expert led recommendations from David Cameron’s obesity plan is just one example of the power the food industry holds over health policy, as tobacco did (and still does) before it. Attempts to include evidence based interventions, such as limits on advertising to children and junk food promotions, and other industry tariffs, were notably missing from the final obesity policy the government released in 2016, which focused on two things: increasing physical activity and reducing sugar intake. Individual solutions for society-wide problems.

As individual choices are not to blame for worsening UK health outcomes, what is? The recent UN report detailed the groups most affected by austerity—older people, children, women, those living with disabilities, asylum seekers, and migrants.11 Many of these groups have seen their health outcomes worsen. The evidence is becoming indisputable: austerity is linked to worsening mental health and suicide rates, worse child health outcomes, and higher mortality among older people.So why announce another plan focusing on individual behaviour?

The UN report concludes, “The experience of the United Kingdom, especially since 2010, underscores the conclusion that poverty is a political choice.” The current unprecedented worsening in health outcomes—specifically, life expectancy and infant mortality—is also a political choice. Telling individuals to “make better choices” is unlikely to halt the decline. Far greater changes are needed to improve the nation’s health, changes requiring political leadership and policies to support social care and healthcare and to narrow widening inequalities.

Experience in other countries shows that major political change can have almost immediate benefits on life expectancy, as seen in East Germany after reunification. The individually focused “prevention plan” is neither new nor seminal and will do nothing to tackle the deepening health crisis in the UK.

click the link here to access the PDF of this editorial and the BMJ online page with rapid responses

—

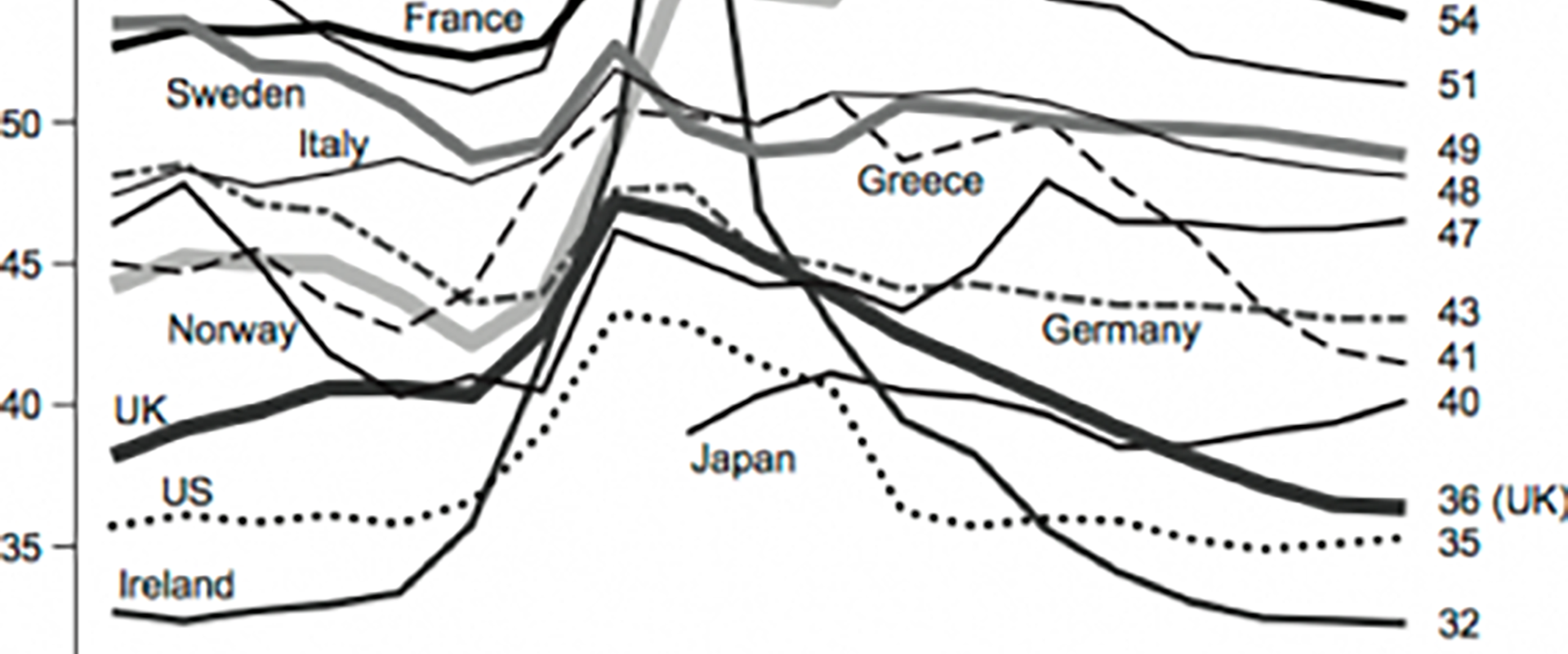

Incidentally, should anyone think that the current crisis has been caused by flu, this is what a flu epidemic looks like:

Typical length of time and severity of influenza epidemics in England, 1960-2000

As Sergei Prokofiev once said, “And so, if you are sitting comfortable, and we are relaxed, we can be begin. Once upon a time, early on morning, Peter opened the gate and went out..”

There is nothing to suggest that flu played the key part the current health crisis, other than the guess in one report: “Of these excess respiratory deaths, pneumonia (specifically ICD-10 code J18) and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (specifically ICD-10 code J44) accounted for the largest proportions. The prominence of pneumonia is likely related to the relationship between EWM and a range of bacterial and viral respiratory pathogens including influenza.”

Government have been referencing flu as the cause for rising mortality every year since 2012. ONS sometimes say it might be flu and at other times have a line towards the end of their reports say “there were no unusual signs of flu’.

Flu epidemics occur infrequently and effect all of Europe (and the northern hemisphere), not just the UK. At some point we will get a real flu epidemic – but what is happening now is like the story of Peter and the Wolf – we need to know when it is the wolf or if what has just happened is Peter shouting wolf for the seventh time. Incidentally at some point someone will need to assign each player in this story to a different instrument. Flu is the french horns. Sergei explains it here.

For anyone interested in the history of government using flu as an excuse when something else was the cause, the story at the beginning of this article might be of interest.

It was published in February 2014 shortly after the first suggestion of “nothing to see, its just flu.” At some point it will be flu. And again, winter is coming. The BMA has warned the “NHS needs 10,000 extra hospital beds this winter to keep patients safe.” But those beds are not being made available. What happens when finally flu does come?

Peter and the Wo

lf