What Brexit tells us about the British

Danny Dorling giving the Institute of Applied Ethics Public Lecture, University of Hull, November 29th 2018, introduced by Colin Tyler.

What Brexit tells us about the British

Whatever kind of Brexit occurs – hard, soft, or even a cancellation and staying in the European Union – the public and especially today’s university students (who mostly had no vote) are going to be asking questions about why this has happened and what it means. A year before this talk was given, extra money had to be found to pay for Brexit in the November 2017 budget than extra that could could be found for the NHS.

In early 2018 there was an unprecedented rise in deaths among elderly people in The UK. On the same day as that budget we also learnt that Britain would lose a place in the International Court of Justice for the first time since the court’s inception in 1946. And then in June 2018 we heard that the NHS would get more funding after all, but far from enough to have a health service as well funded as this in France and Germany.

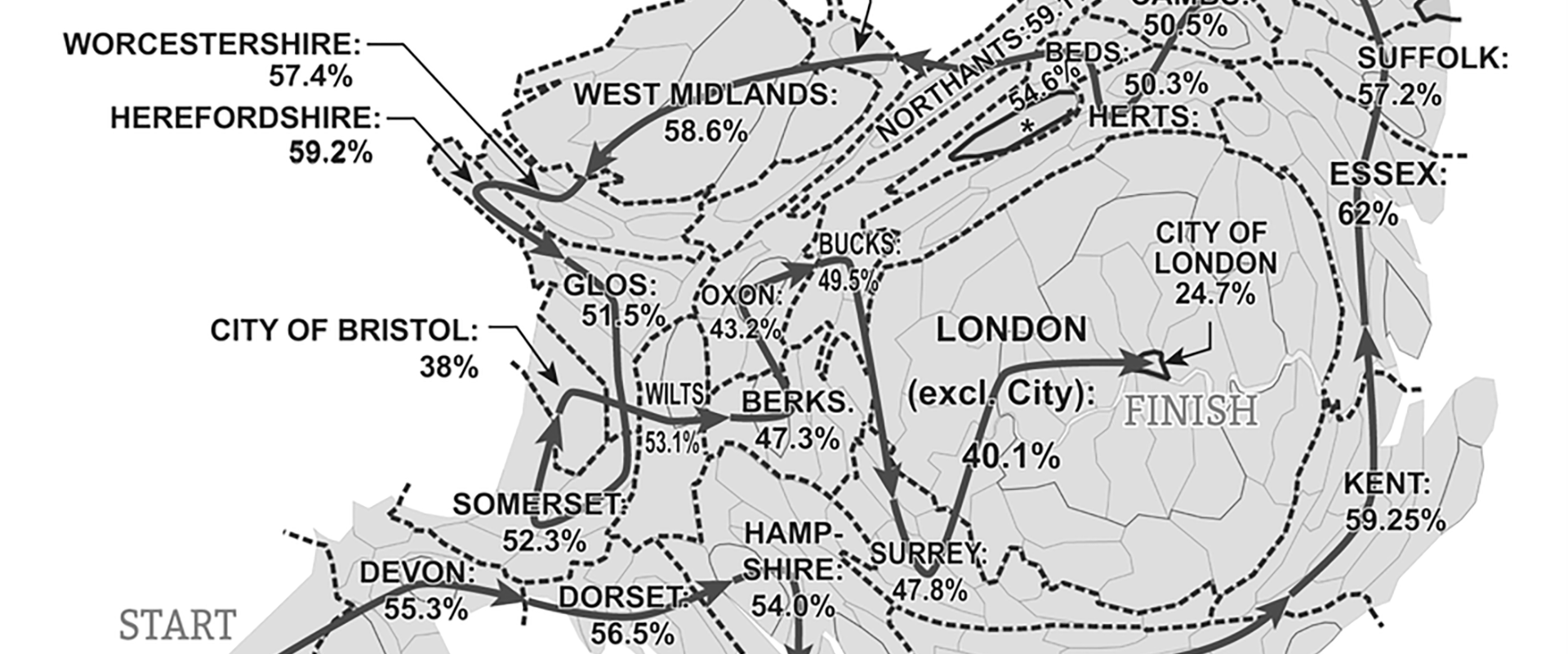

So what can Geographers tell us about Brexit and what does Brexit tell us about the British?

The arguing and making of claims and counter-claims about Britain’s geographical status that is currently underway will not improve the image of Britain in the eyes of much of the rest of the world’s people. But there is an upside. The British may well learn a great deal about themselves as a result. Not least that Britain, and even Brexit, has its roots in the British Empire.

Traditionally British Geography, a subject that was partly born in this country due to Empire has not been very good at explaining what the Empire was and why it mattered. Brexit may well be the point at which the England finally learn about the importance of geography: from the Irish border through to the modern day priorities of India. And we might also learn that how much we fund our health service is choice that we had all along, one that had nothing to do with whether we were in the European Union or not. It was not being in the EU that was our problem – we, it turns out – were the problem, or at least the few of us that took so much and were so unwilling for the rest to be able to live decent lives.

What Brexit tell us about the British